Can the Department of the Air Force and Netflix each have marks for the term "Space Force"?

Can the Department of the Air Force and Netflix each have marks for the term "Space Force"?

It is said that life imitates art far more than art imitates life, but the two have been increasingly blended via television and cinema offerings for over a century. This blending has resulted in multiple instances where television and cinema rights might interfere with real-life rights, and vice versa. One such instance is a developing issue surrounding potential intellectual property rights being granted to the Department of the Air Force (DAF) and Netflix Studios LLC (Netflix).

On December 20, 2019, the United States Space Force (U.S. Space Force) was established as the sixth branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight United States uniformed services, a span of nearly two years since the idea was first proposed by President Donald Trump during a speech given on March 13, 2018. The U.S. Space Force was a re-designation of the Air Force Space Command established on September 1, 1982, a major command of the DAF. Whether by design or happenstance, Netflix green-lit a new comedy series in January 2019 which focused on the creation of a U.S. Space Force. The show, Space Force, was first available for streaming on May 29, 2020.

A brief discussion on trademarks and service marks

Before discussing any relationship between the U.S. Space Force and Space Force, a brief discussion on select portions of United States law with respect to trademarks and service marks may be in order:

- Trademarks are territorial, and with states, countries, and regions of countries (e.g., the European Union) have separately-enforced trademark laws – an applicant for a mark will need to file in each territory in which they would like to enforce their mark.

- The United States system is a first-to-use system, though marks may be filed based on actual use (§ 1(a), or 15 U.S.C. § 1051(a), filing) or based on an intent to use within a particular time frame (§ 1(b), or 15 U.S.C. § 1051(b), filing). Select foreign territories are also first-to-use, but there are a number of first-to-file foreign territories as well.

- Marks in United States law are separated into forty-five (45) classes, with 34 classes for goods (trademarks) and 11 classes for services (service marks).

- Determining whether a mark is being infringed upon includes a consideration of a “likelihood of confusion” between marks, with relevant factors including, but not limited to, similarities of the marks and the nature of the goods and services related to the marks.

- There are defenses to infringement that include uses of parody, especially when the uses are considered in context with First Amendment rights and copyright law.

Can the DAF and Netflix each have marks for the term "Space Force"?

When considering the U.S. Space Force versus Space Force, select marks would likely not be of issue.

Specifically, the DAF could be granted marks under any classes covering or related to the operation and services provided by the U.S. Space Force, while Netflix could be granted marks under any classes covering or related to the production of and the providing of the television series. Defenses of parody and the like aside, there should not be much concern of likelihood of confusion between these granted marks and each party would be able to operate within a sphere granted by their respective mark(s). [1] In addition, to further ensure a safe operating space, an individual or organization (e.g., such as Netflix) wanting to use any mark(s) granted to the DAF could request to do so through the Air Force Licensing program, part of the Air & Space Forces Intellectual Property Management Office. [2][3]

A more difficult issue, however, is where the parties’ spheres start to intersect. One such area may include any classes covering or related to merchandising rights. Depending on the mark(s) granted (e.g., words, symbols, logos, graphics, or the like), it might be more difficult to determine whether the DAF or a third-party (e.g., such as Netflix) is selling a cup, or a t-shirt, or some other piece of branded merchandise.

A fight for merchandising rights

A search for live registrations for “Space Force” filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) as of June 15, 2020 finds eighteen applications including “Space Force” and variants thereof dating from March 13, 2018. One, a trademark for a beer, has been granted a registration number. [4] Four applications are considered dead, having been abandoned. Thirteen applications are still live and pending, of which twelve appear to be directed to possible overlapping interests. Each of the twelve pending applications were filed as a § 1(b) intent-to-use application; however, only two applications were filed by the DAF – a March 13, 2019 [5] filing and a May 20, 2020 filing. [6]

Based on these numbers, then, there are ten pending applications filed by third-parties, either coincidentally or perhaps in response to the original announcement on March 13, 2018, including five filings that predate the Government’s March 13, 2019 filing date. In addition, each of the twelve pending applications were filed on all manner of goods including, but not limited to, clothing, signage, dishware/barware, toys, office and school supplies, electronic devices, food and beverage items, and other merchandise that could be branded with a “Space Force” mark(s) granted to the DAF or a “Space Force” mark granted to a third-party, potentially resulting in confusion between the mark holders [7]

Per the publicly-available file wrappers for each case, all twelve pending applications are either under examination by the USPTO, rejected by the USPTO, [8] suspended by the USPTO due to earlier-filed applications, or entering the appeals process following a rejection – as such, the DAF has not yet lost anything as of June 15, 2020, as far as rights to United States marks are concerned (aside from labeling their own beer).

A note: Although numerous news outlets have focused on Netflix having a stake in the matter with United States trademark filings, [9] Netflix does not appear as an owner for any applications including the phrase “Space Force” despite being listed as the owner for at least 270 live and dead applications with the USPTO, leading to a possible confusion about who actually has a stake in the matter within the United States. Netflix, however, does have both pending applications and active marks in Mexico, Australia, Canada, and in the European Union; the DAF has no international filings at this time.

As this story continues to progress, it will be interesting to see whether the DAF will be granted a mark for “Space Force” for classes related to merchandise, or whether an application filed by a third-party prior to the DAF will instead be granted.

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm providing client-centric patent, trademark, and copyright services. If you need assistance with an intellectual property matter and would like to speak with one of our attorneys, please contact us at info@suiter.com.

Jon S. Horneber is a patent attorney with Suiter Swantz IP. Jon holds a B.S. and M.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Colorado Boulder. Jon received his Juris Doctor from the University of Nebraska College of Law.

Jon joined the Firm as a Law Clerk in 2014. After his 2016 graduation, Jon began working as a patent attorney for the Firm. As a Patent Attorney, Jon prepares and prosecutes U.S. and foreign patent applications.

Jon is admitted to the Nebraska and Colorado Supreme Courts and the U.S. District Court, Districts of Nebraska and Colorado. He is also registered to practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

[1] a note that this is not the first instance of this occurring. For example, Paramount Pictures filed for marks related to the television show “J.A.G.,” which were eventually abandoned, with none registered by the USPTO. It would be interesting to learn whether licensing agreements were obtained from the Department of the Air Force.

[2] The Department of the Navy has a similar licensing office (https://www.navy.mil/trademarks/licensing.html), and C.B.S. having numerous active, pending, and abandoned marks for the television show NCIS. As with J.A.G., it would be interesting to learn whether licensing agreements were obtained from the Department of the Navy.

[3] See also Licensing Programs for the Department of the Army (https://www.defense.gov/Resources/Trademarks/), the United States Marines (https://www.hqmc.marines.mil/ousmcc/trademark/), and the United States Coast Guard (https://www.uscg.mil/Community/trademark/).

[4] Registration No. 5,608,716, filed March 13, 2018 http://tmsearch.uspto.gov/bin/showfield?f=doc&state=4804:rz6u9x.2.18

[5] Serial No. 88/338,255

[6] Serial No. 88/924,951

[7] See e.g., Serial Nos. 87/839,062 and 87/981,611, filed March 19, 2018; Serial No. 88/267,739, filed January 18, 2019

[8] Example rejections including a § 2(a), or 15 U.S.C. § 1052(a), rejection for consisting of or including matter that may falsely suggest a connection with the U.S. Government, its military and Commander in Chief.

[9] https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr-esq/trumps-space-force-lost-first-battle-1296939; in contrast, see https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2020/06/09/who-owns-the-trademark-for-space-force.html

Is the Ruling by the Supreme Court in Iancu v. Brunetti “FUCT” Up?

Is the Ruling by the Supreme Court in Iancu v. Brunetti “FUCT” Up?

In 1990, Erik Brunetti (Brunetti) started the street-wear brand FUCT, pronounced as a spelled-out word F-U-C-T (an acronym for “Friends U (you) Can’t Trust,” according to Brunetti). Since 1993, Brunetti has filed variations of the mark for federal trademark registration, including an application in 2011 for the mark “FUCT.” The 2011 application was denied by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) on the basis of Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act (codified as 15 U.S.C. § 1052(a)) for being directed to “immoral” or “scandalous” matter, terms treated as the same by the USPTO following case law[1], as the USPTO believed a substantial portion of the general public would find “FUCT” vulgar.[2] Brunetti appealed the denial of the mark to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB), which upheld the denial. Brunetti again appealed the denial of the mark to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (Federal Circuit), which found that the clause of § 2(a) used to deny the application for “FUCT” was in violation of the First Amendment, being an unconstitutional restriction of free speech. Following a petition from the USPTO, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) granted certiorari and heard oral arguments on April 15, 2019 for Iancu v. Brunetti, No. 18-302 (U.S. Jun. 24, 2019) (Brunetti).

“FUCT” and “fcuk”

Before discussing the holding in Brunetti, it is worth noting that although “FUCT” ran afoul of § 2(a) of the Lanham Act, other seemingly-similar marks have been granted by the USPTO including, but not limited to, “fcuk” and “FVCK.” In the case of “fcuk” (a play on French Connection UK), the clothing company French Connection applied for and was granted multiple registrations for variations of the mark “fcuk” between 1993 (Brunetti’s first filing) and 2019 (the holding of Brunetti). The registrations of “fcuk” and “FVCK” were presented by John R. Sommer (appearing for Brunetti) during oral arguments of Brunetti as examples of the inconsistent application of § 2(a) of the Lanham Act,[3] along with the question whether § 2(a) of the Lanham Act was overbroad in its construction for being viewpoint-based (as held by the Federal Circuit).[4]

Matal v. Tam

In addition, it is worth noting that Brunetti is not the first time SCOTUS has reviewed the Lanham Act to determine whether a clause violates the freedom of speech guaranteed by the First Amendment. In 2017, SCOTUS held in Matal v. Tam, 137 S. Ct. 1744 (2017)[5] (Tam) that a clause of § 2(a) of the Lanham Act prohibiting registration of a trademark that “[c]onsists of or comprises […] matter which may disparage or falsely suggest a connection with persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them into contempt, or disrepute” was in violation of the First Amendment, with an 8-0 vote. In the Tam decision, it was determined that “[s]peech may not be banned on the ground that it expresses ideas that offend,”[6] as “‘the First Amendment forbids the government to regulate speech in ways that favor some viewpoints or ideas at the expense of others.’"[7] More about Tam may be found in our articles Supreme Court to Review "Disparaging" Trademarks, Supreme Court Hears Oral Arguments in Disparaging Trademark Case, and Supreme Court Makes Decision on Disparaging Trademarks. Please also see our article Redskins Trademark Dispute Ended after Supreme Court Ruling for a discussion about the continued fight for the Washington Redskins trademarks, and our article Use it or Lose it: The Cleveland Indians and Chief Wahoo for a discussion about the discontinuation of the use of the Chief Wahoo logo by the Cleveland Indians.

A Violation of the First Amendment?

Returning to the Brunetti decision, on June 24, 2019, SCOTUS held the clause of § 2(a) of the Lanham Act prohibiting registration of a trademark that “[c]onsists of or comprises immoral […] or scandalous matter” to be in violation of the First Amendment, with a 6-3 vote. In the opinion delivered for the majority, Justice Kagan stated that “the Lanham Act allows registration of marks when their messages accord with, but not when their messages defy, society’s sense of decency or propriety,” such that “the statute, on its face, distinguishes between two opposed sets of ideas: those aligned with conventional moral standards and those hostile to them.”[8] In addition, Justice Kagan stated that “if a trademark registration is viewpoint-based, it is unconstitutional,”[9] as “a law disfavoring ‘ideas that offend’ discriminates based on viewpoint, in violation of the First Amendment.”[10] Further, Justice Kagan stated that “the ‘immoral or scandalous bar’ is substantially overbroad. There are a great many immoral and scandalous ideas in the world (even more than there are swearwords), and the Lanham Act covers them all. It therefore violates the First Amendment.”[11] In this regard, the majority opinion substantially aligned with the Tam decision about “disparaging” marks.

The determining of unconstitutionality in Brunetti, however, was not a requirement that the Lanham Act prohibition of “immoral” or “scandalous” material be removed entirely. Rather, the majority opinion, as well as select concurring opinions and concurring/dissenting opinions, indicated that the decision in Brunetti does not preclude Congress from enacting a statute adopting a narrower approach. According to the Justice Kagan for the majority, “reinterpretation […] mostly restrict[ing] the PTO to refusing marks that are ‘vulgar’-meaning ‘lewd,’ ‘sexually explicit or profane’ [which] would not turn on viewpoint, and so we could uphold it.”[12] In addition, according to Chief Justice Roberts, “standing alone, the term ‘scandalous’ need not be understood to reach marks that offend because of the ideas they convey; it can be read more narrowly to bar only marks that offend because of their mode of expression—marks that are obscene, vulgar, or profane.”[13] Further, according to Justice Alito, the “decision does not prevent Congress from adopting a more carefully focused statute that precludes the registration of marks containing vulgar terms that play no real part in the expression of ideas.”[14]

From a personal perspective, it appears the Justices are commenting on the possibility of limiting the interpretation to categories of speech not protected by the First Amendment (e.g., obscenity, fighting words, or the like)). In addition, it appears the Justices are commenting on the possible incorrectness of past case law which considered “immoral” and “scandalous” to be in the same category, which may (at least in part) have resulted in the determined overreach of the clause of § 2(a) of the Lanham Act.

Is the Holding of Iancu v. Brunetti “FUCT” up, then?

As suggested by Justice Sotomayor, there is perhaps merit in the concern that “[t]he Court’s decision […] will beget unfortunate results”[15] by giving “the Government […] no statutory basis to refuse (and thus no choice but to begin) registering marks containing the most vulgar, profane, or obscene words and images imaginable”[16] and by “permit[ting] a rush to register trademarks for even the most viscerally offensive words and images that one can imagine.”[17] And while “immoral” does appear to be a more nebulous, over-reaching term, “scandalous” may be possible of a narrower interpretation that serves the field of trademark law, one mission of which is to “hel[p] consumers identify goods and services that they wish to purchase, as well as those they want to avoid.”[18]

However, the holding is consistent with the ruling in Tam. In addition, the holding does not run afoul of fashioning a new statute (a power given to Congress) while attempting to interpret the current 15 U.S.C. § 1052(a) by dissecting the clause to remove “immoral” and leave “scandalous” in a narrower form.[19] To this point, the various opinions of Brunetti do suggest that Congress could review this particular clause of § 2(a) of the Lanham Act to determine a narrower interpretation of “immoral” and/or “scandalous” that does not run the possibility of being a viewpoint-based discrimination in conflict with the First Amendment. In this regard, the ruling in Brunetti does ultimately appear to be correct.

In any event, with there now being multiple recent holdings finding against different clauses of § 2(a) of the Lanham Act, the next step may need to come from Congress to consider revising clauses of the Lanham Act which may violate the Constitution and its Amendments. Until a “more carefully focused statute”[20] is passed by Congress, however, decisions such as Brunetti (and Tam) should provide support for the registration of other marks rejected under the guise of “immoral,” “scandalous,” and/or “disparaging.”

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm providing client-centric patent, trademark, and copyright services. If you need assistance with an intellectual property matter and would like to speak with one of our attorneys, please contact us at info@suiter.com.

Jon S. Horneber is a patent attorney with Suiter Swantz IP. Jon holds a B.S. and M.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Colorado Boulder. Jon received his Juris Doctor from the University of Nebraska College of Law.

Jon joined the Firm as a Law Clerk in 2014. After his 2016 graduation, Jon began working as a patent attorney for the Firm. As a Patent Attorney, Jon prepares and prosecutes U.S. and foreign patent applications.

Jon is admitted to the Nebraska and Colorado Supreme Courts and the U.S. District Court, Districts of Nebraska and Colorado. He is also registered to practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

[1] Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP) §§ 1203, 1203.01 (Although the words "immoral" and "scandalous" may have somewhat different connotations, case law has included immoral matter in the same category as scandalous matter. See In re McGinley, 660 F.2d 481, 484 n.6, 211 USPQ 668, 673 n.6 (C.C.P.A. 1981), aff’g 206 USPQ 753 (TTAB 1979) ("Because of our holding, infra, that appellant’s mark is ‘scandalous,’ it is unnecessary to consider whether appellant’s mark is ‘immoral.’ We note the dearth of reported trademark decisions in which the term ‘immoral’ has been directly applied.")).

[2] Id. (The determination of whether a mark is scandalous must be made in the context of the relevant marketplace for the goods or services identified in the application, and must be ascertained from the standpoint of not necessarily a majority, but a "substantial composite of the general public." As long as a substantial composite of the general public would perceive the mark, in context, to have a vulgar meaning, "the mark as a whole ‘consists of or comprises . . . scandalous matter’" under §2(a). In re Fox, 702 F.3d 633, 638, 105 USPQ2d 1247, 1250 (quoting 15 U.S.C. §1052(a) (emphasis added); In re Boulevard Entm’t, Inc., 334 F.3d 1336, 1340, 67 USPQ2d 1475, 1477 (Fed. Cir. 2003); In re McGinley, 660 F.2d 481, 485, 211 USPQ 668, 673.).

[3] See Brunetti, oral arguments at 35-36.

[4] Id. at 32-33, 38-39.

[5] See Matal v. Tam was originally Lee v. Tam. Matal v. Tam is also 582 U.S. __ (U.S. Jun. 19, 2017).

[6] Id. at 1751.

[7] Id. at 1757 (citing to Lamb's Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free School Dist., 508 U.S. 384, 394, 113 S.Ct. 2141, 124 L.Ed.2d 352 (1993)).

[8] See Brunetti, slip op., at 6.

[9] Id. at 4 (citing to Matal v. Tam, 582 U. S., at ___–___, ___–___ (opinion of ALITO, J.) (slip op., at 1–2, 22–23); id., at ___–___, ___ (opinion of Kennedy, J.) (slip op., at 1–2, 5)).

[10] Id. at 8. (citing to 582 U. S., at ___ (opinion of ALITO, J.) (slip op., at 2); see id., at ___–___ (slip op., at 22–23); id., at ___–___ (opinion of Kennedy, J.) (slip op., at 2–3)).

[11] Id. at 11.

[12] Id. at 9.

[13] See Brunetti (Roberts, C.J., concurring/dissenting op., at 2).

[14] See Brunetti (Alito, J., concurring op., at 1).

[15] See Brunetti (Sotomayor, J., concurring/dissenting op., at 1).

[16] Id.

[17] Id. at 18.

[18] See Brunetti (Breyer, J., concurring/dissenting op., at 6) (citing to Matal v. Tam, 582 U.S.__ (slip op., at 2)).

[19] See generally Brunetti, slip op., at 9.

[20] See Brunetti (Alito, J., concurring op., at 1).

A Brief History of Beer and Patents

The brewing of beer has been recorded for over 7,000 years. Originally a by-product of an agrarian culture, the brewing of beer evolved into a domestic profession performed by brewsters (a term historically representing women brewers before the general-neutral term “brewer” became prevalent, as is used today) and then transformed over the last three centuries into the highly industrial and technology-advanced profession of today’s modern society. This transformation was precipitated in part by advances in scientific technologies and instruments such as the thermometer (e.g., the alcohol thermometer and the mercury thermometers, invented by Daniel Fahrenheit) and the hydrometer (e.g., the alcoholometer or proof and Tralles hydrometer invented by Johann Georg Tralles, and the saccharometer invented by Thomas Thomson). In addition, advances in fermentation sciences by chemists Georg Ernst Stahl in the 18th Century and Louis Pasteur in the 19th Century resulted in brewed beer that has less bacteria and a longer shelf life.

In the United States, beer has been brewed since the late 16th century. The brewing of beer has also been both directly and indirectly affected by legislative Acts passed by Congress and judicial rulings handed down by the courts for over two hundred years. For instance, the National Prohibition Act (Volstead Act) created Prohibition in 1919 by enabling the 18th Amendment, and the Cullen-Harrison Act amended the National Prohibition Act to pave the way to the repeal of Prohibition with the 21st Amendment in 1933.

In addition, President Jimmy Carter signed H.R. 1337 on October 14, 1978, which included an amendment creating an exemption from taxation of beer brewed at home for personal or family use. The amendment in H.R. 1337 effectively legalized homebrewing on a federal level in the United States on February 1, 1979. In addition, the amendment is credited, at least in part, for the craft brewery explosion over the last 40 years as H.R. 1337 allowed states to pass laws regulating homebrewing under the powers granted to them by the 21st Amendment (which front-runner states like California, Oregon, and Washington passed by 1983, while the last states Alabama and Mississippi did not pass until 2013).

Further, legislation passed in numerous Acts over the last 225 years have created and modified the United States patent system that provides the means for granting and/or enforcing patent rights, and the means for defending against those patent rights being granted and/or enforced. Similarly, courts around the nation have shaped the patent system for over 200 years.

Since the first Patent Act of 1790, inventors have been issued patents for thousands of inventions including “beer” or “brewing” in the title with the various patent offices and agencies (e.g., the United States Patent and Trademark Office, or USPTO) of the United States Government.

Some inventions focus on the brewing of beer itself, including:

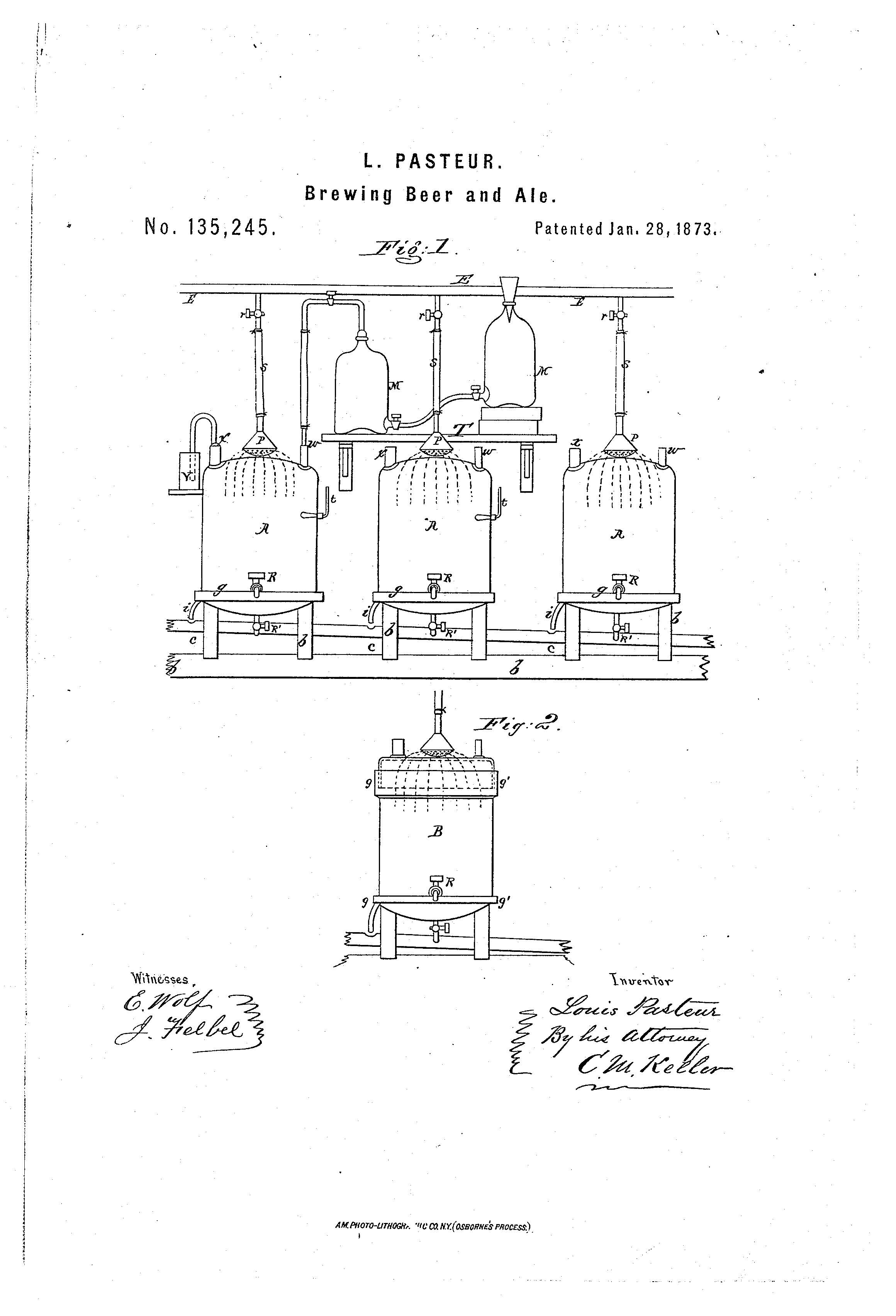

- Patent No. 135,245 was issued on January 28, 1873, to Louis Pasteur for his work with fermentation in the patent titled an “Improvement in Brewing Beer and Ale” (pasteurization).

- Patent No. 868 was issued on August 1, 1838, to Thomas Behan for an “Improvement in Brewing Beer and Ale.” Further, Patent No. 1,551,979 issued September 1, 1925, to Henry Deckebach, for a “Process and Apparatus for Making Beer of Low Alcoholic Content.” Of note here is that the ‘979 patent includes a description of a “means of removing alcohol from beer [without affecting taste] and recovering the alcohol that is removed,” and was filed in 1919 between the ratifying of the National Prohibition Act in 1919 and Prohibition going into effect in 1920.

- Patent No. 5,811,144 was issued on September 22, 1998, to assignee Labatt Brewing Company Limited for “Beer Having Increased Light Stability and Process of Making.”

- Other inventions focus on the technologies necessary for the transportation and distribution of beer, including Patent No. 172,687 issued on January 25, 1876, to Louis Baeppler for an “Improvement to Beer Coolers.”

- Patent No. 664,824 was issued on December 25, 1900, to Gottlieb Schmidt and assigned to Harry E. Bell and Emma Schmidt for a “Cold-Air-Pressure Apparatus for Beer or other Fluids.”

- Patent No. 2,575,658 was issued on November 20, 1951, to Nero Roger Del for a “Beer Faucet.”

- Design Patent No. D188,371 was issued on July 12, 1960, for a “Beer Fermenting Tank.”

- Patent No. 3,065,885 was issued on November 27, 1962, to assignee Anheuser-Busch Companies LLC for a “Beer Barrel Tapping Device.”

- Patent No. D411,710 was issued on June 29, 1999, to assignee The Boston Beer Company for a “Tap Handle.”

Still other inventions focus on drinkware for beer, including:

- Numerous design patents, such as:

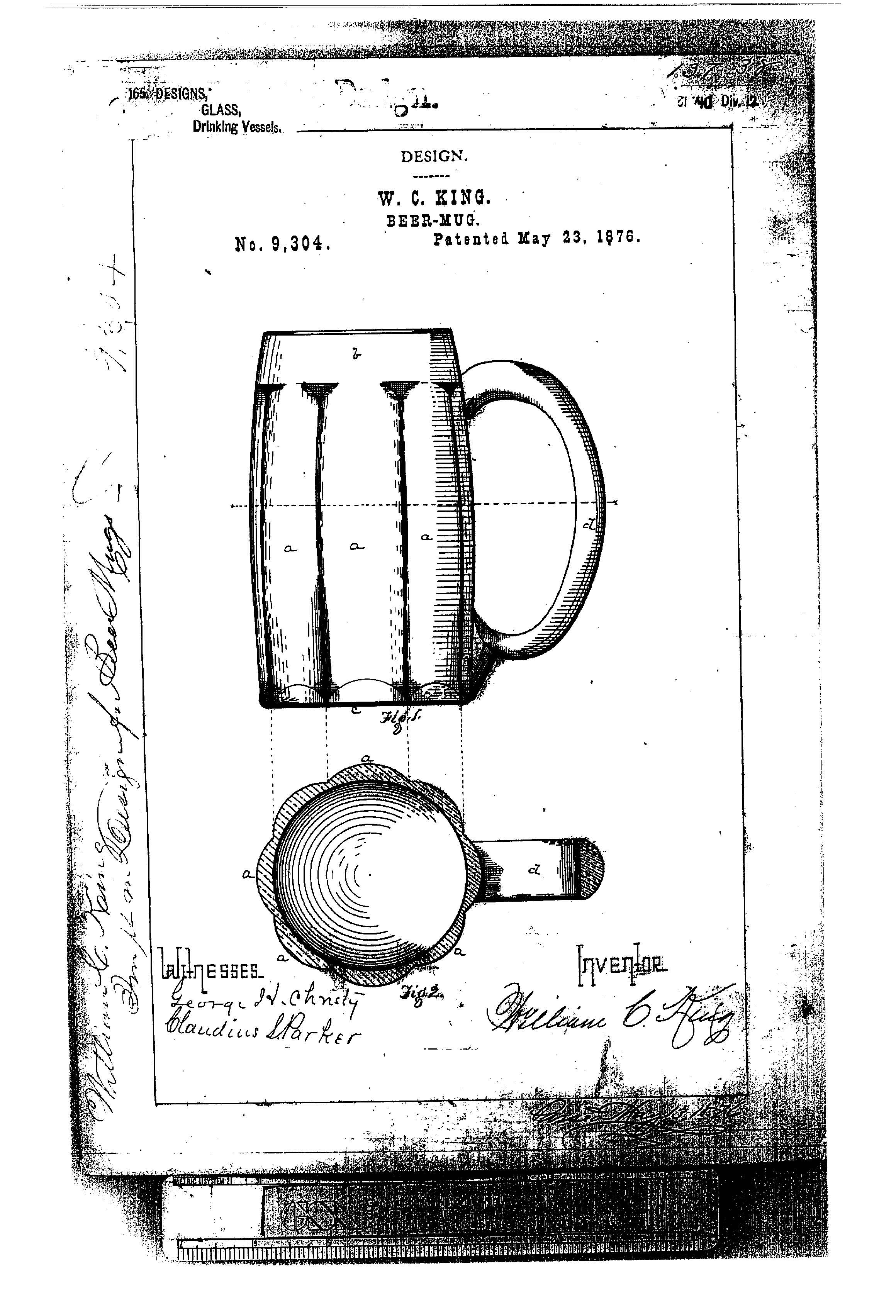

- Patent No. 146,078 issued December 30, 1873, to W. C. King for “Beer-Mugs.”

- Patent No. 6,659,298 issued December 9, 2003, to assignee to Zhuhai Zhong Fu PET Beer Bottle Co Ltd. For a “Polyester Beer Bottle.”

Although the focus here is on the patent system being utilized to protect rights in inventions related to beer, it is worth noting that beer itself has been provided as a reward for the making of scientific advances. For example, the Carlsberg Brewery outside of Copenhagen, Denmark provided an Honorary Residence with a direct pipeline to the factory next door. Per the will of the Carlsberg founder, Jacob Christian Jacobsen, the Carlsberg Honorary Residence was to occupied by ‘‘a man or a woman [picked by the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters] deserving of esteem from the community by reason of services to science, literature, or art, or for other reasons.” The most notable resident of the Honorary Residence is Niels Bohr, who was given the Carlsberg Honorary Residence for his work on the hydrogen atom, living there from 1932 until his death in 1962. After the passing of the last resident in 1995, the Carlsberg Honorary Residence became the Carlsberg Academy, which includes a conference center for the Royal Academy and an apartment for a visiting foreign scientist.

While Carlsberg is fresh on the mind, Carlsberg and Heineken jointly own patents EP2384110 and EP 2373514 that were granted by the European Patent Office (EPO) in 2016, which protect a barley strain defined as improving the taste of beer and allowing for a more energy-efficient brewing process. These patents are currently being contested as protecting barley strains that are bred through conventional means of barley cultivation and beer brewing (as opposed to being genetically engineered), thus allegedly violating an EPO patent law which prohibits patents on conventional breeding. It is will be interesting to see how this case comes out, because it represents another case in a bank of high-profile, international biotechnology cases and because it may affect the fundamental processes brewers have used for hundreds of years to cultivate and brew with barley.

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm, based in Omaha, NE, serving all of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. If you have any intellectual property questions or need assistance with any patent, trademark, or copyright matters and would like to speak with one of our patent attorneys please contact us.

Recent Developments Regarding the Use of Inter Partes Review Proceedings to Challenge Patents

I. Introduction

Inter partes review (IPR) is a trial proceeding conducted before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). An alternative to filing in a Federal District Court, a third-party may file an IPR proceeding with the PTAB to challenge the validity of an issued patent based on select criteria. In the last eighteen months, there have been multiple developments regarding the use of IPR proceedings, including whether state sovereign immunity under the Eleventh Amendment may be invoked as a defense in an IPR proceeding, whether tribal sovereign immunity may be invoked as a defense in an IPR proceeding, and whether IPR proceedings are constitutional. This article will discuss the background behind the recent developments, initial responses to the recent developments, and possible outcomes to the recent developments.

II. A Discussion about Inter Parts Review (IPR) and Sovereign Immunity

A. Patents and inter partes review (IPR)

A patent is a type of intellectual property (IP) resulting from Congress acting upon its power provided by Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the Constitution to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”[1] Originally created by the Patent Act of 1790, the United States patent system has undergone several major revisions in the last 200+ years, including the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act of 2011.[2]

Patent prosecution is the process of writing and filing a patent application, and subsequent interaction with the USPTO. If patent prosecution is successful, the USPTO issues a patent. The patent term, or life, for an issued patent is generally twenty years from the filing date or claimed priority dates prior to the filing date, but this can be adjusted by a number of factors.[3] Per 35 U.S.C. § 271, an issued patent provides a patent owner the right to exclude others from making, using, offering to sell, or selling any patented invention, within the United States or importing into the United States any patented invention during the term of the patent.[4] Infringing an issued patent includes acting against the patent owner’s right to exclude others and/or actively inducing a third party to act against the patent owner’s right to exclude others.[5]

Issued patents may be challenged by third-parties as being invalid, meaning the issued patent fails to meet statutory requirements (e.g., the patent is not patentable subject matter,[6] is anticipated by prior art,[7] is obvious based on prior art,[8] does not conform to drafting and specification requirements,[9] or the like) and thus should not have been granted by the USPTO. Patent challenges are often filed by a defendant of an infringement suit filed by the patent owner or by a party to pre-emptively strike and prevent a possible infringement lawsuit, but may be filed by any third-party who is not the owner.

Patent challenges may be brought in a Federal District Court, as federal courts have original jurisdiction over state courts for any civil action relating to patents.[10] Alternatively, patents may be challenges via inter partes review (IPR) before a Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) panel of administrative law judges (ALJ). The America Invents Act of 2011 established the PTAB and its IPR proceedings to replace inter partes reexaminations, which the USPTO first instituted in 1981.[11] In an IPR proceeding, an issued patent may only be challenged as being invalid on grounds of anticipation or obviousness; in addition, the issued patent may only be challenged on the basis of only prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.[12] If, in a petition to the PTAB, the challenger can show there is a reasonable likelihood of prevailing in invalidating at least one challenged claim, a PTAB panel will institute an IPR proceeding.[13] Any party dissatisfied with the finding by the PTAB panel during the IPR proceeding may appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC).[14

B. Sovereign Immunity

One limitation on the authority of state and federal courts is the concept of sovereign immunity, which the federal government, state governments, and tribal governments may invoke.[15] The concept of sovereign immunity in the United States derives its origins from the English common law legal maxim that “the King can do no wrong.”[16] Sovereign immunity may be invoked as a defense by a governing body in a lawsuit, unless the defense is waived by one entitled to invoke the defense, is abrogated by an Act of Congress,[17] or falls within an exception defined by the Supreme Court.[18]

1.State Sovereign Immunity and The Eleventh Amendment

State governments and state agencies[19] have sovereign immunity under the Eleventh Amendment, which states: “[t]he Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.”[20] Congress passed the Eleventh Amendment in response to Chisholm v. Georgia, in which the Supreme Court upheld an estate executor’s claim against the state of Georgia for repayment of military supplies for the American Revolutionary War.[21]

The language of the Eleventh Amendment, as adopted, appeared to prohibit federal courts from hearing suits against a state only if brought by citizens of another state or a foreign country; however, in Hans v. Louisiana the Supreme Court interpreted the language of the Eleventh Amendment to include the prohibition of federal courts from hearing suits brought by citizens of the state being sued.[22] In addition, the Supreme Court held in Federal Maritime Commission v. South Carolina State Ports Authority that the defense of state sovereign immunity extends to federal administrative proceedings that have a “remarkably strong resemblance to civil litigation in federal courts.”[23]

The PTAB has twice considered the question whether state sovereign immunity could be applied to inter partes review. On January 25, 2017, the PTAB dismissed three IPR proceedings instituted against patents owned by the University of Florida Research Foundation (UFRF) on grounds of state sovereign immunity as afforded by the Eleventh Amendment.[24] Similarly, on May 23, 2017, the PTAB dismissed an IPR proceeding instituted against patents owned by the University of Maryland, Baltimore.[25] In both instances, a PTAB panel found that the universities could not be the subject of legal proceedings brought by a private party because the universities are state agencies, and allowed the universities to invoke state sovereign immunity against the respective IPR proceedings.[26]

2. Tribal Sovereign Immunity

Support for the concept of tribal sovereign immunity is not found in the Eleventh Amendment, unlike state sovereign immunity but instead extends from Article I of the Constitution and subsequent Supreme Court decisions.[27] Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the Constitution grants Congress the power “[t]o regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.”[28] In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the Supreme Court interpreted the separation of “Indian Tribes” from “foreign Nations” and “the several States” to mean tribes were “domestic dependent nations” of the United States, with a relationship like that of a “ward to its guardian.”[29] The right to a sovereign immunity defense was afforded to Indian tribes in Turner v. United States, in which the Supreme Court held that “[w]ithout authorization from Congress, the [Oklahoma Creek] Nation could not … have been sued in any court; at least without its consent.”[30]

Today, after 175 years of caselaw,[31] the United States acknowledges select Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, and other tribal entities “to have the immunities and privileges available to federally recognized Indian Tribes by virtue of their government-to-government relationship with the United States as well as the responsibilities, powers, limitations, and obligations of such Tribes.”[32] These “immunities and privileges” may only be abrogated by an Act of Congress or waived by an Indian Tribe, Tribal Nation, or other tribal entity.[33] In this regard, although tribal sovereign immunity is not explicitly afforded to Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, and other tribal entities by the Constitution, it exists in a nearly-equivalent form as determined by Supreme Court precedent.

III. Invoking Tribal Sovereign Immunity

A. Why Invoke Tribal Sovereign Immunity?

Tribal sovereign immunity serves to “promote economic development and tribal self-sufficiency,”[34] making the existence of sovereign immunity important to Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, and other tribal entities. For many Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, or other tribal entities, promoting economic development and tribal self-sufficiency is a difficult task. Standard channels of income for a government such as property taxes are not available to Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, or other tribal entities as Indian reservations are held in trust by the United States.[35] In addition, despite the misconception that many Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, and other tribal entities generate income from gambling casinos and tobacco sales,[36] those actually doing so are few in number and located across the nation.[37]

The difficulty to promote economic development, combined with increased levels of unemployment and poverty,[38] has many Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, and other tribal entities searching for new methods to generate the desired economic development and tribal self-sufficiency. These new methods include procuring business opportunities in the field of electronics, oil and gas, manufacturing, distribution, logistics, and more.[39] In addition, Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, and other tribal entities are starting to obtain patents from patent owners, and license the obtained patents to interested parties. One recent instance of this type of transaction is the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe (the Tribe) obtaining the RESTASIS® patent portfolio from Allergan, Inc. (Allergan), and licensing the patent portfolio back to Allergan.

B. Allergan, Inc. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals and the transfer of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to the Tribe

Allergan is a pharmaceutical company that markets health care products for a number of medical sectors.[40] The health care product RESTASIS® (Cyclosporine Ophthalmic Emulsion) 0.05% is an eye drop that helps increase the eyes’ natural ability to produce tears.[41] The patent portfolio for RESTASIS®, as listed in the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Orange Book, includes U.S. Patent Nos. 8,629,111 (the ‘111 patent), 8,633,162 (the ‘162 patent), 8,642,556 (the ‘556 patent), 8,648,048 (the ‘048 patent), 8,685,930 (the ‘930 patent), and 9,248,191 (the ‘191 patent), all of which are set to expire in 2024.[42] The RESTASIS® patent portfolio protected improvements to a prior version of the RESTASIS® formulation protected by U.S. Patent No. 5,474,979 (the ‘979 patent), which expired in 2014.[43]

On August 24, 2015, Allergan filed patent infringement suits against Teva Pharmaceuticals (Teva), Mylan Pharmaceuticals (Mylan), and other pharmaceutical companies in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, following the filing of applications challenging the RESTASIS® patent portfolio and the announcement by Teva and Mylan of an intention to make generic versions of RESTASIS®.[44] On December 8, 2016, Mylan petitioned the PTAB to challenge the RESTASIS® patent portfolio.[45] Although the six patents in the RESTASIS® patent portfolio all stem from a common non-provisional patent application, and claim priority to a common provisional application, a PTAB panel instituted six separate inter partes review proceedings in response to Mylan’s petition.[46] With the six IPR proceedings co-pending before the PTAB, U.S. District Judge William Bryson presided over the trial for the patent infringement suit in the District Court for the Eastern District of Texas on August 28-31, 2017.[47]

On September 8, 2017, as previously discussed by the firm, Allergan transferred the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe (the Tribe), a sovereign nation crossing the border between New York State and Canada, in exchange for an exclusive license to practice the patent-protected IP.[48] In exchange for the exclusive license, the Tribe received the RESTASIS® patent portfolio and 13.75 million dollars, and will continue to receive 15 million dollars annually while the RESTASIS® patent portfolio remains enforceable (e.g., until invalidated or until 2024, when all six patents expire).[49]

During a telephone hearing held on September 11, 2016, the Tribe announced it would seek a stay of the six instituted IPR proceedings, claiming the right to tribal sovereign immunity.[50] Richard Torczon, representing Mylan, expressed his belief that Allergan’s sale of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to the Tribe was only a “sham” transaction, as the Tribe did not purchase the portfolio but rather was paid to take the portfolio.[51] Michael Shore, council for the Tribe, responded to the claims of a “sham transaction” by offering forth an explanation of the benefits to both parties.[52] True to its announcement, the Tribe filed a Motion to Dismiss on September 22, 2017, and a Corrected Motion to Dismiss on October 3, 2017, in each of the six IPR proceedings.[53] In the Corrected Motion to Dismiss, the Tribe noted Supreme Court precedent regarding the existence of tribal sovereign immunity, and indicated its belief that its right to invoke tribal sovereign immunity was neither abrogated nor waived.[54]

The Tribe also explained its belief that dismissing the IPR proceedings on the grounds of tribal sovereign immunity would “not deprive [Mylan] of an adequate remedy [but] only deprives [Mylan] of multiple bites at the same apple.”[55] Notably, while the Tribe sought a stay on the six IPR proceedings, it did not similarly seek a stay on the patent infringement suit being deliberated on in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. On September 8, 2017, following the transfer of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to the Tribe, Allergan informed U.S. District Judge William Bryson that it would add the Tribe as a co-plaintiff to the litigation pending before him.[56] After Allergan did not submit the necessary motions to join the Tribe, however, U.S. District Judge Bryson filed an Order on October 6, 2017, requiring both sides to file briefs addressing the question whether the Tribe should be joined as a co-plaintiff or whether the Court should disregard the assignment of the patents as a sham.[57]

On October 16, 2017, U.S. District Judge Bryson handed down an opinion invalidating the RESTASIS® patent portfolio.[58] In his opinion, U.S. District Judge Bryson held that, despite submitted declarations regarding the unexpected and surprising benefits of the improved RESTASIS® formulation protected by the six patents in the RESTASIS® patent portfolio,[59] the improved RESTASIS® formulation it “did not perform significantly better than other formulations known to Allergan.”[60] As a result, the Court found the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to be obvious in light of at least Allergan’s ‘979 patent.[61]

Along with his opinion invalidating the RESTASIS® patent portfolio, U.S. District Judge Bryson filed a Memorandum Opinion and Order joining the Tribe as a co-plaintiff to the patent infringement suit.[62] In the memorandum, U.S. District Judge Bryson clarified that the Tribe should be joined as a co-plaintiff to the infringement suit before the Court to prevent the “judgment entered by the Court [from being] subject to challenge on the ground that the owner of the patents was not a party to the action” should it be “later determined that the Tribe is a valid owner of the patents.” In this regard, U.S. District Judge Bryson “adopt[ed] the safer course of joining the Tribe as a coplaintiff (sic), while leaving the question of the validity of the assignment to be decided in the IPR proceedings, where it is directly presented.”[63]

Interestingly, the idea of “leaving the question of the validity of the assignment to be decided in the IPR proceedings” did not prevent U.S. District Judge Bryson from discussing Allergan’s transfer of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to the Tribe. U.S. District Judge Bryson stated that “[t]he Court has serious concerns about the legitimacy of the tactic that Allergan and the Tribe have employed” as it appeared that “[Allergan] has paid the Tribe to allow Allergan to purchase—or perhaps more precisely, to rent—the Tribe's sovereign immunity in order to defeat the pending IPR proceedings in the PTO.”[64] In addition, U.S. District Judge Bryson questioned “the validity of the assignment and exclusive license transaction” and “whether the Tribe is an owner of the RESTASIS® patents within the meaning of the Patent Act,” although the issues did not bear on the District Court’s power to hear the infringement suit.”[65] Further, U.S. District Judge Bryson discussed the possible damage to IPR proceedings should similar patent portfolio transfers be allowed to occur, stating:

Allergan, which does not enjoy sovereign immunity, has invoked the benefits of the patent system and has obtained valuable patent protection for its product, Restasis. But when faced with the possibility that the PTO would determine that those patents should not have been issued, Allergan has sought to prevent the PTO from reconsidering its original issuance decision. What Allergan seeks is the right to continue to enjoy the considerable benefits of the U.S. patent system without accepting the limits that Congress has placed on those benefits through the administrative mechanism for canceling invalid patents.

If that ploy succeeds, any patentee facing IPR proceedings would presumably be able to defeat those proceedings by employing the same artifice. In short, Allergan's tactic, if successful, could spell the end of the PTO's IPR program, which was a central component of the America Invents Act of 2011.[66]

IV. Possible Outcome

A. Should the Tribe’s Motion to Dismiss in the six inter partes review proceedings be granted?

Although Judge Bryson discusses some salient points in regard to the transferring of patent portfolios to Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, or other tribal entities and the subsequent invoking of tribal sovereign immunity in IPR proceedings, his discussion largely acts as dicta. Not only were the issues of the validity of the patent portfolio transfer and the invoking of tribal sovereign immunity in IPR proceedings not presented before the District Court, the District Court was not “required to decide whether the assignment of the patent rights from Allergan to the Tribe was valid.”[67] Instead, those issues are before the PTAB panel following the Tribe’s filing of its Motions to Dismiss in the six IPR proceedings. The PTAB panel will first need to consider (1) whether the contract between Allergan and the Tribe included the necessary consideration, such that the Tribe are the owners of the patent. If so, then the PTAB panel will need to consider (2) whether tribal sovereign immunity may be invoked with inter partes review. If tribal sovereign immunity is applicable, the PTAB panel will need to consider (3) whether the Tribe is prevented from invoking because (a) an Act of Congress has abrogated the right to invoke tribal sovereign immunity in the RESTASIS® patent portfolio IPR proceedings or (b) the Tribe waived the right to invoke tribal sovereign immunity in the RESTASIS® patent portfolio in IPR proceedings.

Regarding Issue (1), although Mylan may believe the transfer of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio is a “sham transaction,” consideration validating the contractual agreement between Allergan and the Tribe appears to exist to prevent a similar finding by the PTAB panel.[68] In addition, the Tribe had obtained forty patents from the tech company SRC Labs in an August 2017 agreement prior to the transfer of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio from Allergan,[69] suggesting a commitment towards enforcing patent rights as a means of generating economic development and tribal self-sufficiency.

Regarding Issue (2), PTAB precedent allows state sovereign immunity to be invoked in response to an IPR proceeding.[70] In addition, Supreme Court precedent documents the near-equivalency between state sovereign immunity and tribal sovereign immunity.[71] As such, it is plausible that tribal sovereign immunity will be found to be applicable as a defense in an IPR proceeding.

Regarding Issue (3a), Congress has not yet passed a statute that would abrogate the right to invoke tribal sovereign immunity in the RESTASIS® patent portfolio IPR proceedings. Regarding Issue (3b), the actions by the Tribe, including at least the language in the filed Motions to Dismiss, indicates the Tribe has not waived the right to invoke tribal sovereign immunity during in the RESTASIS® patent portfolio IPR proceedings.[72]

As such, it is reasonable for the PTAB panel will find tribal sovereign immunity to be applicable as a defense to IPR proceedings and grant the Motions to Dismiss for the six IPR proceedings.

B. End Tribal Sovereign Immunity for IPR Proceedings?

While the question of invoking tribal sovereign immunity in an IPR proceeding is considered by the PTAB panel, new patent infringement suits for patents transferred to Indian Tribes, Tribal Nations, or other tribal entities are starting to show up on court dockets. In March 2017, the Texas technology company ProWire sued Apple for royalties , claiming Apple’s iPad 4 infringed on ProWire’s U.S. Patent No. 6,137,390 (the ‘390 patent).[73] After filing the patent infringement suit, ProWire transferred the ‘390 patent to MEC Resources LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nations (the Three Affiliated Tribes), in August 2017.[74] In October 2017, the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe and SRC Labs, as co-plaintiffs, filed patent infringement lawsuits against Amazon and Microsoft, claiming infringement of a combination of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,076,152 (the ‘152 patent), 6,247,110 (the ‘110 patent), 6,434,687 (the ‘687 patent), 7,225,324 (the ‘324 patent), 7,421,524 (the ‘524 patent), 7,620,800 (the ‘800 patent), 7,149,867 (the ‘867 patent), and 9,153,311 (the 311 patent), which SRC Labs transferred to the Tribe in August 2017.[75]

Appearing to recognize the potential increase in patent portfolio transfers and subsequent invoking of tribal sovereign immunity, Congressional members responded swiftly to the transferring of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to the Tribe. On September 27, 2017, Senators Maggie Hassan (D-NH), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), Bob Casey (D-PA), and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) sent a letter to Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Ranking Member Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), calling the transferring of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to the Tribe “a blatantly anti-competitive attempt to shield its patents from review and keep drug prices high.”[76] On October 3, 2017, the U.S. House of Representatives Oversight and Government Reform Committee requested that Allergan provide documents about its preparation and completion of agreements with the Tribe, financial details about the RESTASIS® drug, and information about possible future deals of a similar nature, claiming concerns of the type of arrangement “impair[ing] competition across the pharmaceutical industry.”[77] On October 5, 2017, Senator McCaskill (D-MO) introduced bill S.1948 to the 115th Congress, which is designed to abrogate tribal sovereign immunity as a defense to IPR proceedings.[78] The bill,[79] which only states “ [n]otwithstanding any other provision of law, an Indian tribe may not assert sovereign immunity as a defense in a review that is conducted under chapter 31 of title 35, United States code,”[80] would serve as an act of Congress to abrogate tribal sovereign immunity in regard to IPR proceedings.[81]

Allergen, the Tribe, and other interested parties responded with equal swiftness. On October 3, 2017, Allergan responded to the claims by Senators Hassan, Brown, Casey, and Blumenthal in a letter to Senators Grassley and Feinstein, noting that the validity of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio was also pending before the District Court of the Eastern District of Texas and criticizing the “flawed and broken IPR process.”[82] On October 12, 2017, the Tribe sent a letter to Senators Grassley and Feinstein about the current financial status of the Tribe, the Tribe’s displeasure to the double standard being applied against the invoking of tribal sovereign immunity versus the invoking of state sovereign immunity in IPR proceedings, and the perceived impact the current IPR process has on pharmaceutical patent portfolios.[83] Also on October 12, 2017, the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), representing over 1,100 medical field entities, sent a letter to Senators Grassley and Feinstein expressing the organization’s concern about the current nature of the IPR process.[84] Also on that day, the organization United Southern and Eastern Tribes adopted a resolution to take all steps necessary to oppose Congressional abrogation of tribal sovereign immunity in regard to further amendments of the AIA.[85]

Given the swiftness with which members of Congress responded to the news regarding the transfer of the RESTASIS® patent portfolio to the Tribe, one might expect legislative actions to be forthcoming in the near future. However, if a statute were enacted based on the bill as introduced by Sen. McCaskill or based on similar language, the statute may run into issues of constitutionality. The Sen. McCaskill bill does not affect state sovereign immunity, as it is protected by the Eleventh Amendment; although tribal sovereign immunity does not have protection under the Eleventh Amendment, Supreme Court precedent does provide a nearly-equivalent level of support. In addition, the bill is intended to prevent invoking tribal sovereign immunity in IPR proceedings, but is not directed to preventing the invoking tribal sovereign immunity in post grant review (PGR) proceedings and covered business method (CBM) proceedings before the PTAB, or invoking tribal sovereign immunity in Federal District Court proceedings.

C. End Inter Partes Review?

Although invoking tribal sovereign immunity for inter partes review is currently under attack, criticism has plagued the IPR process for some time. One criticism is that the IPR process heavily favors patent challengers, which places patent owners at a marked disadvantage.[86] Per data compiled for the first five years of IPR proceedings instituted between September 2012 and September 2017, 65% of the PTAB’s final written decisions invalidate all claims in a challenged patent and 81% of final written decisions invalidate at least one claim in a challenged patent.[87] In addition, it has statistically been considerably less to bring a challenge before the PTAB instead of in a Federal District Court (e.g., hundreds of thousands versus tens of millions), which allows for a larger pool of third-party challengers.[88] Another criticism is the ability to re-contest patents through serial petitioning until the patent is completely invalidated and/or the ability to work around statute of limitations through motions for joinder with other challengers.[89] These concerns have culminated in introduced legislation to revise the IPR process and the granting of certiorari by the Supreme Court to review the constitutionality of the IPR process.

1. STRONGER Patents Act of 2017

One attempt to change revise the IPR process, as previously discussed by the firm, is via the Support Technology and Research for Our Nation’s Growth and Economic Resilience Patents Act of 2017, or the STRONGER Patents Act of 2017, introduced by Senator Chris Coons (D-AK).[90] The STRONGER Patents Act of 2017 includes a number of provisions that would redefine the IPR process, making it more patent owner-friendly. Challenged claims would be presumed valid, and the level of proof for overcoming of the presumed validity would be increased from “preponderance of the evidence” to “clear and convincing evidence.”[91] In addition, only a defendant to a patent infringement suit or an individual who is under a threat of legal action for which the individual might seek a declaratory judgment will be able to challenge a patent via an IPR proceeding.[92] Further, a particular patent could only be challenged once via an IPR proceeding, meaning multiple petitions cannot be filed (even if new prior art is found), and review by a Federal District Court precludes revisiting of the patent via an instituted IPR proceeding.[93] Further still, the patent owner is effectively entitled to amend claims or file for “expedited reexamination” with the USPTO without the patent challenger’s involvement.[94] Under the STRONGER Patents Act, the pendulum would almost certainly swing back towards the patent owner.

2. Oil States Energy Services v. Greene’s Energy Group

Another attempt to change the IPR process includes the question presented in Oil States Energy Services v. Greene’s Energy Group (Oil States), which the Supreme Court heard during the October 2017 term. Oil States filed against Greene’s Energy Group for infringement of Oil States’ U.S. Patent No. 6,179,053 (the ‘053 patent). Greene’s filed an IPR proceeding with the PTAB, which invalidated the ‘053 patent. Oil States appealed the invalidation to the CAFC and, following the CAFC’s denial, appealed to the Supreme Court.[95]

On October 27, 2017,[96] as previously discussed by the firm, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments[97] regarding the question “whether inter partes review – an adversarial process used by the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) to analyze the validity of existing patents – violates the Constitution by extinguishing private property rights through a non-Article III forum without a jury.”[98] Initial impressions from the oral arguments point to a possible decision that would allow the IPR proceedings to continue as they are, letting the USPTO correct improperly-granted patents.[99] Alternatively, an alternative holding may eliminate the IPR process, requiring that all re-examinations of patents (if a found to be a private property right) need to be done by the Judicial Branch.[100]

It seems improbable that the Supreme Court uphold IPR proceedings without providing guidance about how to adjust the IPR process; however, if this were to occur, the patent process itself may be adjusted (e.g., thorough prior art searches, narrower claim sets in drafts, and more detailed examination during individual patent and patent portfolio acquisition, or the like).[101]

It also seems improbable that the Supreme Court will completely eliminate the IPR process. Finding IPR proceedings to be unconstitutional may result in the vacating of thousands of decisions since the creation of IPR proceedings in 2012. In addition, a finding that IPR proceedings, an Executive branch administrative process, encroaches on the powers afforded to the Judicial Branch may affect how other Executive Branch agencies operate.[102]

Ultimately, it seems most plausible that the Supreme Court will allow IPR proceedings before a PTAB panel to continue, and in addition may provide guidance in regard to refining the IPR process in an attempt to prevent damaging a patent owner’s private property rights and/or encroaching on the power afforded to the Judicial branch. Even with this outcome, it is plausible that patent owners would see a swinging of the pendulum towards protecting the rights of the patent owner in some form.[103]

Guidance from the Supreme Court regarding IPR proceedings, however, may result in questions as to whether it is actually IPR proceedings that need adjustment, or instead the patent prosecution review process. Whether IPR proceedings or the patent prosecution process requires adjustment is dependent at least in part on whether the percentages provided above (65%/81%) are indicative of PTAB panel overzealousness or improper Examiner review during the patent prosecution process. For example, if the percentages have resulted from PTAB panels being too heavy-handed when utilizing the power given to them, then adjustment to IPR proceedings may be necessary. In the alternative, if the percentages have resulted from PTAB panels utilizing the power given to them in moderation and after careful review, then adjustment to the patent prosecution process and Examiner review may be necessary to reduce the number of improperly-granted patents. This would require an objective review of the data upon which the provided percentages are based, which is beyond the scope of this article.

V. Closing Remarks

For a patent owner concerned about the effect inter partes review proceedings may have on held patent portfolios, any means of protection from an IPR proceeding may look promising. The recent developments regarding the use of IPR proceedings, however, are still too unresolved to be relied upon. Transferring a patent portfolio to an Indian Tribe, Tribal Nation, or other tribal entity in exchange for an exclusive license to practice the protected invention may appear to provide some protection from third-party challenged, but Congress appears willing to abrogate the right to invoke tribal sovereign immunity in an IPR proceeding. In addition, the STRONGER Patents Act of 2017 (if it passes) and the Supreme Court’s review in Oil States of the constitutionality of the IPR process may change the IPR process, but the most plausible result is that the IPR process will not be entirely rescinded.

If anything, the uncertainty in the IPR process resulting from the recent developments illustrates not the need to find ways to remove a held patent portfolio from post-issuance review proceedings, but instead the need to ensure a patent is well-drafted and correctly prosecuted. A well-drafted, correctly prosecuted patent has been the surest method to protect one’s intellectual property rights from post-issuance challenges in the past, and will likely continue to be the surest method for the foreseeable future.

Author note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Suiter Swantz IP or the official policy or position of any agency of the U.S. government. Examples of legal analysis and determining of possible case holdings performed within this article are only examples, and are based on limited and dated open source information.

Printed (Adapted or printed in part) by permission from the author and the Nebraska State Bar Association, to be published in The Nebraska Lawyer, January/February 2018.

[1] U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8, cl. 8.

[2] See e.g., Patent Act of 1952, Leahy-Smith America Invents Act of 2011.

[3] See e.g., Patent Term Adjustment, Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) 2733, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2733.html. Double Patenting, MPEP 804, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s804.html.

[4] 35 U.S.C. § 271(a) (2010).

[5] 35 U.S.C. §§ 271(a),(b) (2010).

[6] 35 U.S.C. § 101 (1952).

[7] 35 U.S.C. § 102 (2012).

[8] 35 U.S.C. § 103 (2011).

[9] 35 U.S.C. § 112 (2011).

[10] 28 U.S.C. § 1338(a) (2011).

[11]Id.; see also Neal Solomon, The Problem of Inter-Partes Review (IPR), IPWatchdog, 8 Aug. 2017, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/08/08/problem-inter-partes-review-ipr/id=86287/.

[12]Patent Trial and Appeal Board, USPTO (2017), https://www.uspto.gov/patents-application-process/patent-trial-and-appeal-board-0.

[13] Id.

[14] MPEP 1216, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s1216.html.

[15] However, the Eleventh Amendment does not bar suits against political subdivisions of a state or municipalities, meaning local governments may be sued in federal court. See e.g., Mt. Healthy City School Dist. Bd. Of Educ. V. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977); see also Lincoln County v. Luning, 133 U.S. 529 (1890).

[16] Erwin Chemerinsky, Against Sovereign Immunity, 53 STAN. L. REV. 1201-1224, 1201 (2001), https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/775.

[17] See e.g., Federal Torts Claims Act, 28 U.S.C. §§ 2671-2680 (1946).

[18] See e.g., Obsorn v. Bank of the United States, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 738 (1824) (holding that the Eleventh Amendment precludes suits against a state only when the state is named as a defendant); see also Tindal v. Wesley, 167 U.S. 204 (1897) and Ex Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) (holding that the Eleventh Amendment does not preclude suits against state officers for injunctive relief).

[19] See Pennhurst State School and Hospital v. Halderman, 465 U.S. 89, 100 (1984); see also Savage v. Glendale Union High School, 343 F.3d 1036, 1040-41 (9th Cir. 2003); Belanger v. Madera Unified School District, 963 F.2d 248 (9th Cir. 1992), cert. denied, 507 U.S. 919 (1993). Febres v. Camden Board of Education, 445 F.3d 227, 229 (3d Cir. 2006).

[20] U.S. Const. amend. XI.

[21] Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 419 (1793).

[22] Erwin Chemerinsky, Constitutional law--Principles and policies, Wolters Kluwer Law & Business (2011) (citing to Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1, 18 (1890) (holding that it would be “anomalous” to allow states to be sued by their own citizens); aff’d by Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44, 69 (1996))).

[23] Federal Maritime Commission v. South Carolina State Ports Authority, 535 U.S. 743, 757 (2002).

[24] Steve Brachmann, UFRF’s win on Eleventh Amendment at PTAB creates IPR immunity for public universities, IPWatchdog, 16 Mar. 2017, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/03/16/ufrf-eleventh-amendment-defense-ptab-creates-ipr-immunity-iprs-public-universities/id=79341/ (Brachmann1); see also Order Dismissing Petitions for Inter Partes Review Based on Sovereign Immunity, Covidien LP v. Univ. of Fl. Research Foundation Inc., IPR2016-01274 (PTAB 2017).

[25] Stephen Gardner et al., Sovereign Immunity of Patents: While a Strong Benefit to Patent Owners, These Patents Remain Subject to Traditional Challenges, IPWatchdog, 19 Jun. 2017, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/06/19/sovereign-immunity-patents-benefit-patent-owners-patents-remain-subject-traditional-challenges/id=84589/ (citing to NeoChord, Inc. v. Univ. of Md., Baltimore, IPR2016-00208 (PTAB 2017)).

[26] Steve Brachmann, Allergan’s patent transaction with St. Regis Mohawks could presage more arbitrage patent transactions, IPWatchdog, 18. Sep. 2017, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/09/18/allergans-patent-transaction-with-st-regis-mohawks-could-presage-more-arbitrage-patent-transactions/id=87970/ (Brachmann2).

[27] However, many argue that tribal sovereign immunity is inherent, as it existed prior to colonization of North America and the formation of the United States.

[28] U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8, cl. 3.

[29] Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. 1, 13 (1831). See also Johnson v. M’Intosh (21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823) and Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832).

[30] Turner v. United States, 248 U.S. 354 (1919); aff’d by United States v. United States Fidelity & Guaranty Co., 309 U.S. 506, 512 (1940) (“Indian tribes are exempt from suit without Congressional authorization”).

[31] See e.g., Puyallup Tribe, Inc. v. Dep’t of Game, 433 U.S. 165 (1977); Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978); Okla. Tax Comm’n v. Citizen Band Potawatomi Indian Tribe of Okla., 498 U.S. 505 (1991); Kiowa Tribe of Okla. v. Mfg. Techs. Inc., 523 U.S. 751 (1998); Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community, 134 S.Ct. 2024 (2014).

[32] Fed. Reg., Vol. 82, No. 10, January 17, 2017.

[33] See C & L Enterprises, Inc. v. Citizen Band Potawatomi Indian Tribe of Oklahoma, 532 U.S. 411, 418 (2001) ( “To abrogate tribal immunity, Congress must “unequivocally” express that purpose … Similarly, to relinquish its immunity, a tribe's waiver must be “clear.”).

[34] Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma v. Manufacturing Technologies, Inc., 523 U.S. 751, 757 (1998).

[35] Frequently Asked Questions – Why Tribes Exist Today in the United States, U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affars (2017) (“A federal Indian reservation is an area of land reserved for a tribe or tribes under treaty or other agreement with the United States, executive order, or federal statute or administrative action as permanent tribal homelands, and where the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe.”); see also Washington State Department of Revenue, Information for tribal members/citizens - Property Tax, (“When tribal lands are held in trust by the Federal Government, that property and the improvements on it are exempt from property taxes when owned by a tribe or its members/citizens.”) https://dor.wa.gov/get-form-or-publication/publications-subject/tax-topics/information-tribal-memberscitizens

[36] Brachmann2, supra (quoting Dale White, general counsel for the Tribe: “This is something that we need because our primary source of revenue is the casino, and that can’t last forever so we’re trying to diversify”).

[37] Greg Ablavsky, Tribal Sovereign Immunity and Patent Law, Stanford Law School Blogs, 13 Sep. 2017, https://law.stanford.edu/2017/09/13/tribal-sovereign-immunity-and-patent-law/.

[38] Id.

[39] Paul Morinville, Native Americans Set to Save the Patent System, IPWatchdog, 9 Oct. 2017, http:// http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/10/09/native-americans-set-save-patent-system/id=88871/.

[40] Key Products, Allergan, 2017, https://www.allergan.com/products/key-products

[41] Allergan, Allergan Comments on PTAB Decision Regarding Mylan's Petitions for Inter Partes Review (IPR) of RESTASIS® Patents, 8 Dec. 2016, https://www.allergan.com/News/News/Thomson-Reuters/Allergan-Comments-on-PTAB-Decision-Regarding-Mylan (Allergan1).

[42] Gene Quinn, PTAB institutes Mylan IPR challenges on Allergan patents for RESTASIS, IPWatchdog, 13 Dec. 2016, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2016/12/13/ptab-institutes-mylan-ipr-allergan-patents-restasis/id=75645/ (Quinn1).

[43] Findings of Fact and Conclusion of Law, 7, infra.

[44] Quinn1, supra. See also Joe Mullin, Judge wants to know if Allergan’s tribal patent deal is a “sham”, Ars Technica, 11 Oct. 2017, https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/10/judge-wants-to-know-if-allergans-tribal-patent-deal-is-a-sham/ (Mullin1).

[45] Id. See also Kevin Penton, PTAB agrees to review Allergan RESTASIS patents, Law360, 9 Dec. 2016, https://www.law360.com/articles/871046/ptab-agrees-to-review-allergan-restasis-patents.

[46] Quinn1, supra.

[47] Docket for Allergan, Inc. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc (2:15-cv-01455), CourtListener, https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/4388062/allergan-inc-v-teva-pharmaceuticals-usa-inc/?page=5.

[48] Brachmann1, supra; see also Allergan, Allergan and Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Announce Agreements Regarding RESTASIS® Patents, 8 Sep. 2017, https://www.allergan.com/News/News/Thomson-Reuters/Allergan-and-Saint-Regis-Mohawk-Tribe-Announce-Agr (Allergan2).

[49] Joe Mullin, Drug company Hands Patents off to Native American Tribe to Avoid Challenge, Ars Technica, 13 Sep. 2017, https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/09/how-a-native-american-tribe-ended-up-owning-six-key-patents-on-an-eye-drug/ (Mullin2).

[50] See Steve Brachmann, Mylan calls Allergan’s patent deal with Indian tribe a “sham” transaction in PTAB hearing on sovereign immunity defense, IPWatchdog, 13 Sep. 2017, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/09/13/mylan-calls-allergans-patent-deal-st-regis-tribe-sham-ptab-sovereign-immunity/id=87928/. (Brachmann3).

[51] Id.

[52] Brachmann2, supra (quoting Michael Shore, representing the Tribe in the six IPR: “[i]f you can avoid IPRs, there’s a huge value difference between patents which can be subject to IPRs and patents that are not, […] a significant enough difference that if you can find a sovereign which is willing to take advantage of that arbitrage, there is money to be made there.”).

[53] Gene Quinn, Indian Tribe files Motion to Dismiss RESTASIS Patent Challenge based on Sovereign Immunity, IPWatchdog, 22 Sep. 2017, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/09/22/indian-tribe-files-motion-to-dismiss-patent-challenge-based-on-sovereign-immunity/id=88201/ (Quinn2); see also Corrected Patent Owner’s Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Jurisdiction Based on Tribal Sovereign Immunity, Docket No. IPR2016-01127 (PTAB 2016).

[54] Corrected Patent Owner’s Motion to Dismiss, supra. (“The Tribe is a sovereign government that cannot be sued unless Congress unequivocally abrogates its immunity or the Tribe expressly waives it. […] Neither of these exceptions apply here. As Patent Owner, the Tribe is an indispensable party to this proceeding whose interests cannot be protected in its absence.”).

[55] Id. (“The Tribe will not assert sovereign immunity in the Eastern District of Texas case […] [s]o dismissing this case does not deprive the Petitioners of an adequate remedy; it only deprives them of multiple bites at the same apple.”; see also Allergan2, supra.

[56] Alison Frankel, Texas Judge Posed to Decide if Allergan Patent Deal with Mohawks was a Sham, Reuters, 11 Oct. 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-otc-allergan/texas-judge-poised-to-decide-if-allergan-patent-deal-with-mohawks-was-a-sham-idUSKBN1CG2NK (citing to the Letter to Judge William C. Bryson from Fish and Richardson dated September 8, 2017, https://static.reuters.com/resources/media/editorial/20171011/allerganvteva--noticeofassignment.pdf).

[57] Frankel, supra.

[58] Findings of Fact and Conclusion of Law, Allergan Inc, v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., (16 Oct. 2017), http://www.ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/523-Allergan-Opinion.pdf, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/4110280/523-Allergan-Opinion.pdf.

[59] Id. at 21.

[60] Id. at 67.

[61] Id. at 134-35. See also Joe Mullin, Judge Throws out Allergan Patent, Slams Company’s Native American Deal, Ars Technica, 16 Oct. 2017, https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/10/judge-throws-out-allergan-patent-slams-companys-native-american-deal/ (Mullin3).

[62] Memorandum Opinion and Order, Allergan Inc, v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 170825, https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/4388062/522/allergan-inc-v-teva-pharmaceuticals-usa-inc/.

[63] Id. at 17-18.

[64] Id. at 10.

[65] Id. at 16.

[66] Id. at 10-11.

[67] Id. at 8.

[68] See Section III.B of this article.

[69] Joe Mullin, Native American Tribe Sues Amazon and Microsoft Over Patents, Ars Technica, 18 Oct. 2017, https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/10/native-american-tribe-sues-amazon-and-microsoft-over-patents/ (Mullin4).

[70] See Section II.B.1 of this article.

[71] See Section II.B.2 of this article.

[72] See Section III.B of this article.

[73] Joe Mullin, Apple is Being Sued for Patent Infringement by a Native American Tribe, Ars Technica, 27 Sep. 2017, https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/09/apple-is-being-sued-for-patent-infringement-by-a-native-american-tribe/ (Mullin5).

[74] Id.

[75] Mullin4, supra.

[76] Jan Wolfe, Senators want probe of Allergan Transfer Deal with Tribe: Letter, Reuters, 9 Sep. 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-allergan-patents/senators-want-probe-of-allergan-transfer-deal-with-tribe-letter-idUSKCN1C22VY (citing the Letter to Senator Grassley and Senator Feinstein from Senator Hassan dated September 27, 2017, https://www.hassan.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/170927.%20Grassley%20Feinstein%20Restasis%20Letter%20FINAL%20SIGNED.PDF).

[77] Michael Erman, U.S. House Committee Launches Probe of Allergan Patent Deal, Reuters, 3 Oct. 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-allergan-patents/u-s-house-committee-launches-probe-of-allergan-patent-deal-idUSKCN1C8262?il=0 (citing the Letter to Allergan CEO Brenton Saunders from House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform dated October 3, 2017, https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017-10-03-TG-DR-EC-PW-to-Saunders-Allergan-Restasis-due-10-17.pdf).

[78] Gene Quinn, Senator McCaskill introduces bill to abrogate Native American Sovereign Immunity, IPWatchdog, 5 Oct. 2017, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/10/05/senator-mccaskill-legislation-abrogate-native-american-sovereign-immunity/id=88975/ (Quinn3).

[79] A Bill To abrogate the sovereign immunity of Indian tribes as a defense in inter partes review of patents, S. 1948, 115th Cong., 1st sess. (2017).

[80] 35 U.S.C. Ch. 31, §§ 311-19 – INTER PARTES REVIEW.

[81] Joe Mullin, New bill would end Native American “sovereign immunity” for patents, Ars Technica, 9 Oct. 2017, https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/10/new-bill-would-end-native-american-sovereign-immunity-for-patents/ (Mullin6).