On January 20, 2015, the Supreme Court decided that a district court’s factual findings would receive an added degree of deference. Rather than be treated under de novo review, the Supreme Court held that factual findings made by a district court in determining claim construction will be reviewed under a clear error standard. The fallout of such a holding will be manifest in years to come. Nevertheless, practitioners were given a glimpse at how the effects will be felt when the Federal Circuit took up the case on remand.[2]

On remand, the Federal Circuit reconsidered the factual findings made by the district court, specifically those made with respect to testimony given by Teva’s expert, Dr. Grant. Despite reconsideration, the Federal Circuit held their ground, reaffirming that their prior determination of indefiniteness had been a legal determination. In other words, under the de novo standard of review with respect to claim construction, and under the clear error standard of review with respect to the factual aspects of Dr. Grant’s testimony (i.e., regarding the meaning of ‘molecular weight’ despite the use of a chromatogram and calibration curve in one of Teva’s examples), Teva’s claims to a method for manufacturing copolymer-1 as defined by its molecular weight are indefinite due to the multiple definitions that exist for the term ‘molecular weight.’

The Federal Circuit reached their holding in part due to prosecution history that gave different meaning to the disputed term than the meaning relied on by Teva during litigation. In light of the conflicting uses of the disputed term, the Federal Circuit’s burden of reaching a legal conclusion without disregarding factual findings unless there was clear error was diminished. In fact, it would have been more interesting to see what decision would have been reached had the prosecution history been in favor of, or at least silent with respect to, Teva’s litigated definition of the term. Had there been no conflicting uses of the term, the Federal Circuit would have been required to more carefully consider and weigh the District Court’s factual findings to reach its conclusion.

Nevertheless, because the prosecution history was not in Teva’s favor, the Federal Circuit held the claims to be indefinite and gave this sobering reminder, “The public notice function of a patent and its prosecution history requires that a patentee be held to what he declares during the prosecution of his patent.” Springs Window Fashions LP v. Novo Indus., L.P., 323 F.3d 989, 995 (Fed. Cir. 2003). In other words, practitioners who are unsure about the meaning of a claim term, as understood by those skilled in the art, should think twice before establishing a record that could be the linchpin for infringers and potentially result in the death of a client’s patent.

Another effect of the Teva holding may be a reduction in the number of cases relying on § 112 to challenge validity. This is foreseeable because as the District Court receives a greater degree of deference, appeals to the Federal Circuit regarding claim construction and ultimately validity will be harder to win. Therefore, the number of § 112 cases cited at the Federal Circuit level will likely decline.

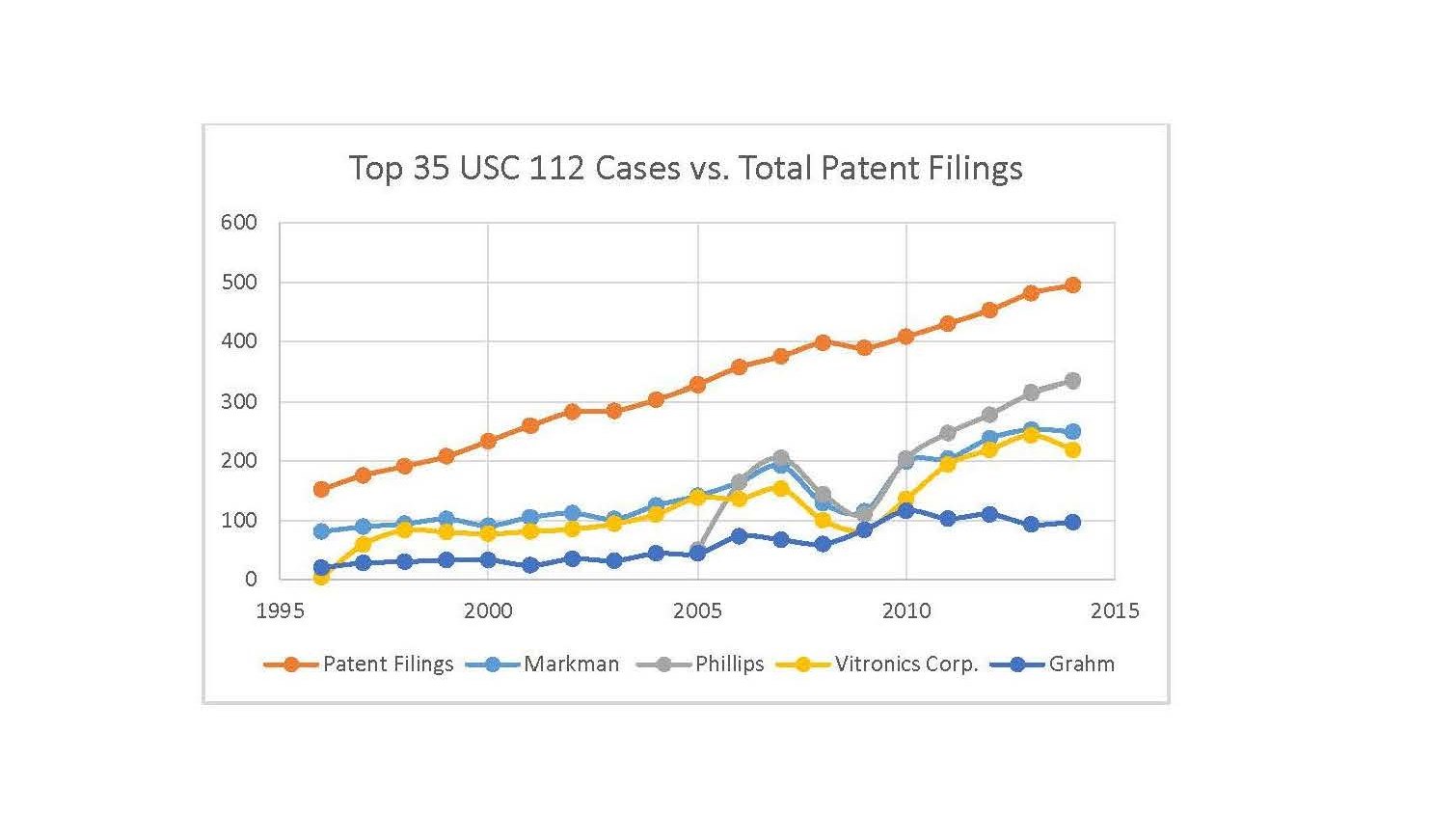

The following graph shows the frequency of some of the top-cited § 112 cases versus the frequency of patent filings:

The cases utilized are Markman[3], Phillips[4], Vitronics Corp.[5] and Graham[6] and the patent filings are scaled by 0.0008. Obviously Graham is not a § 112 case, but I was interested to see how a top-cited § 103 case correlated with patent filings.

As shown above, in more recent years (e.g., 2010-2014) there appears to be a fairly strong correlation between § 112 cases cited and patent filings. In contrast, Graham appears to show little correlation.

My prediction is that these associations will reverse. In other words, the § 112 cases cited (at least at the appellate level) will begin to decline in light of Teva. Furthermore, although there is little correlation now between patent filings and cases citing § 103, parties appealing cases to the Federal Circuit will rely more often on precedent from § 103 cases (and § 101 cases due to Alice[7]). The reversal will occur because like issues dealing with § 101, the issues with § 103 are less factual (i.e., requiring a greater degree of judgement). Because these issues are less factual, they will have a higher likelihood of success at the Federal Circuit because they will likely receive the de novo standard of review.

The repercussions of the added deference granted in Teva will take time to fully comprehend. Nevertheless, one effect is certain. Practitioners need to continue to be vigilant when prosecution history is being established.

[1] Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., No. 13-854, slip op. (S. Ct. Jan. 2015).

[2] Teva Pharm. USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., No. 12-1567-1570 (Fed. Cir. Jun., 18. 2015).

[3] Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 52 F.3d 967 (Fed.Cir. 1995).

[4] Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed.Cir. 2005).

[5] Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576 (Fed.Cir. 1996).

[6] Graham v. John Deere Co. of Kansas City, 86 S.Ct. 684 (1966).

[7] Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. __, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).