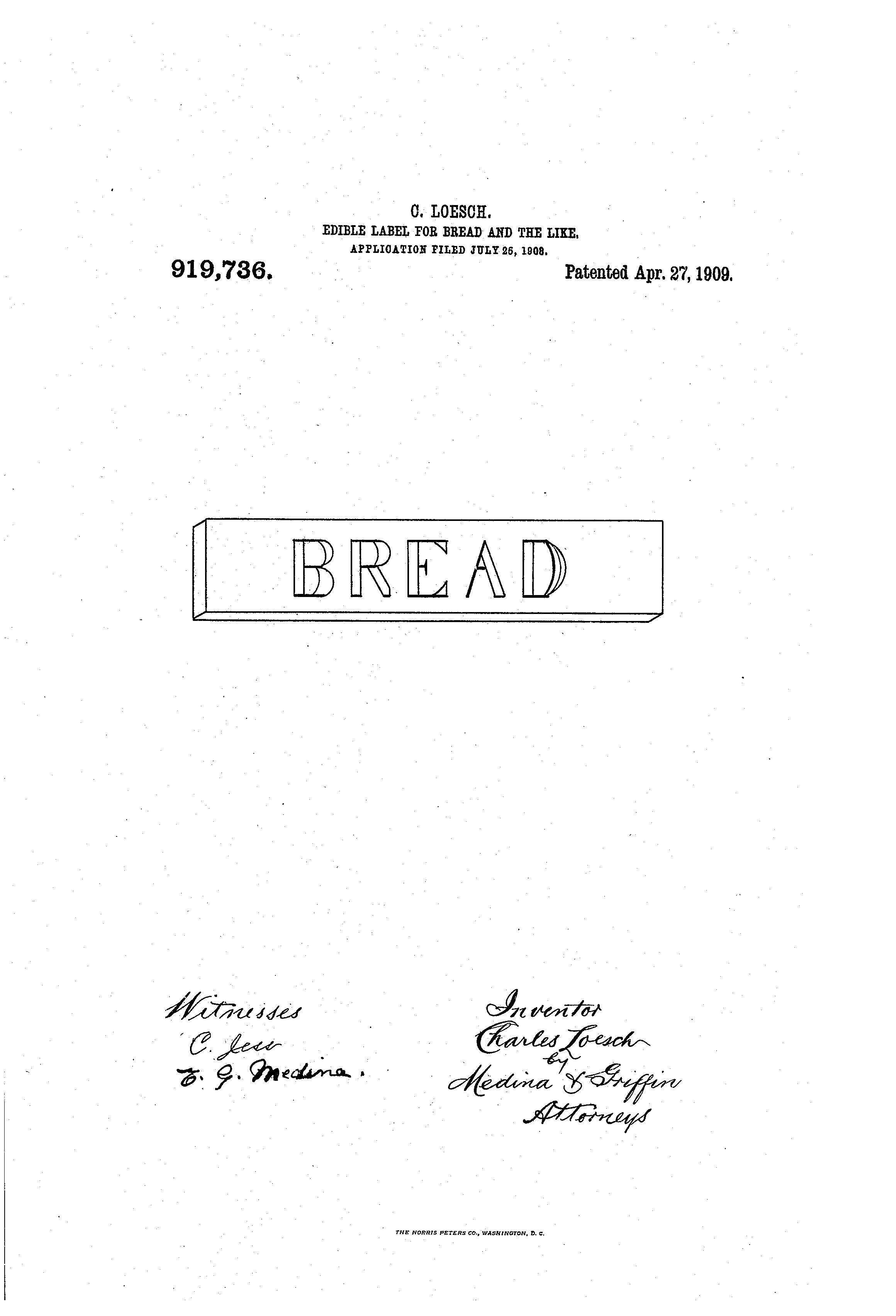

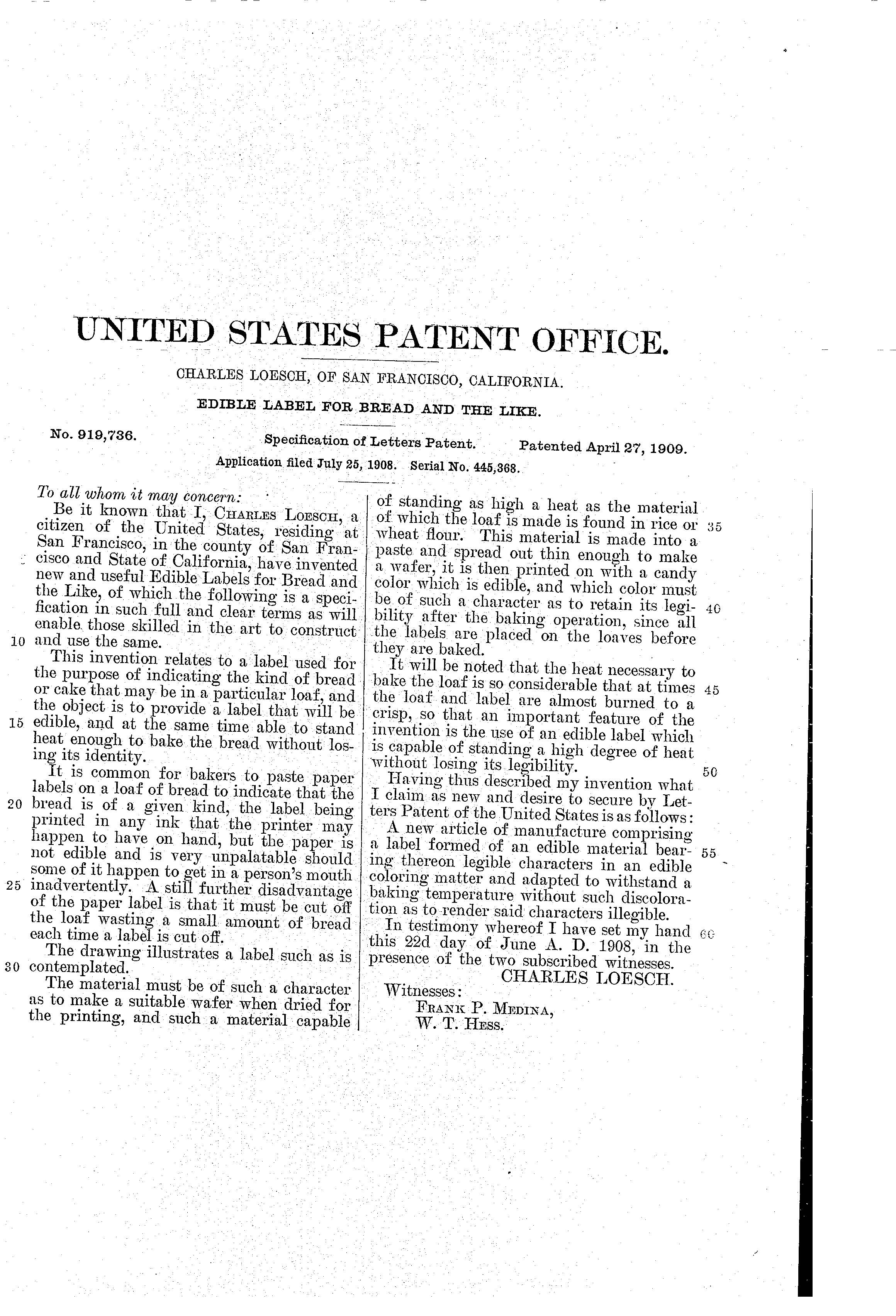

Patent of the Day: Edible Label for Bread and the Like

On this day in 1909 the patent for Edible Label for Bread and the Like was granted. U.S. Patent No. 919,736.

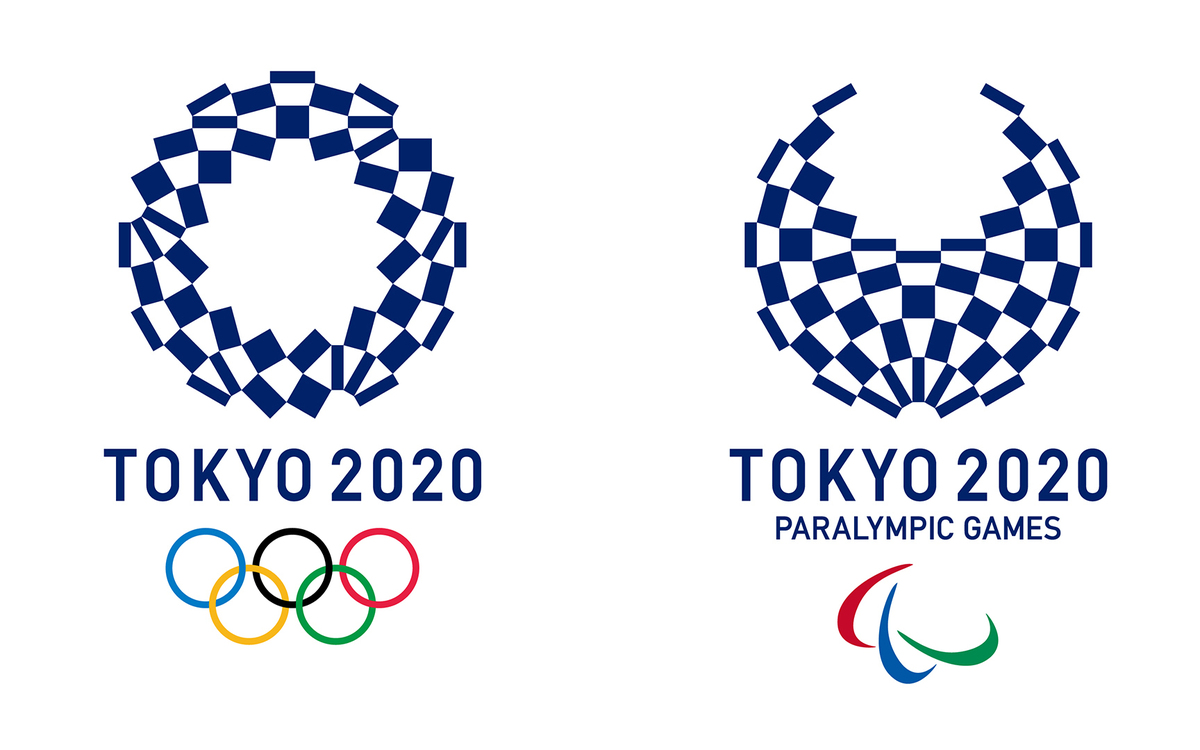

Plagiarism Accusations and the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

Seven months ago the organizers of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics released their logo for the games, but had to quickly revamp it as they were accused of plagiarism. Kenjiro Sano, the original designer, was accused of plagiarizing the emblem of a Belgian playhouse; Sano maintains his work is original, but the committee was forced to get a new design and designer. On April 25th, the committee released the new logo.

The “Harmonized chequered emblem” logo is based on “ichimatsu moyo” design from Japan’s Edo era (1603-1868), a period of shogunate rule and isolationist foreign policy. The designer, Asao Tokolo, composed three varieties of rectangular shapes to represent different countries, cultures and ways of thinking. He also sought to have the design promote diversity as a platform to connect the world as the Olympics do.

This logo is not the only set back Tokyo has had in the way of the Olympics. The costs associated with the Olympic Stadium have grown to be more expensive than original estimates. The original estimate for the futuristic design by the late British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, was 163 billion yen, which was quickly abandoned when the price escalated to 252 billion yen ($2.3 Billion). The new design, estimated to cost 149 billion yen, will be designed by Kengo Kuma and is slated to be completed by November 2019.

U.S. Supreme Court to Weigh in On Inter Partes Review (IPR) Proceedings

Oral arguments for Cuozzo Speed Technologies v. Lee were heard by the United States Supreme Court (SCOTUS) on Monday April 25, 2016. One of the primary questions SCOTUS was faced with was whether the United States government has made it too easy for companies to challenge competitors’ patents via a procedure known as inter partes review (IPR). IPR is a newly implemented review function that was put into effect with the implementation of the America Invents Act (AIA) of September 16, 2012. IPR is held in front of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), which is an administrative board, existing within the executive branch. IPR proceedings are in addition to the traditional route, which take place in federal court, giving opponents of a patent two avenues to invalidate a competitor’s patent.

SCOTUS is determining whether it is appropriate for the PTAB to review patent validity under a “broadest reasonable interpretation” (BRI) standard. In contrast, federal courts apply a plain and ordinary meaning standard when evaluating patent scope. This distinction is important because the BRI standard generally leads to an interpretation of broader claim scope, making it easier to find prior art that overlaps with the claim scope of the patent in question. Put another way, the BRI standard makes it easier for a reviewer to find publications that show a patent does not cover something new and non-obvious.

Chief Justice Roberts found the IPR process to be “a bizarre way to . . . decide a legal question” and noted "it’s a very extraordinary animal in legal culture to have two different proceedings addressing the same question that lead to different results.” Justice Roberts went on to suggest that the PTAB should apply the same standard as used by federal courts.

Justice Kagan seemed to blame Congress for the confusion in stating “If I look at the statute, I mean, it just doesn’t say one way or the other."

Justice Breyer was more understanding of the USPTO’s position and suggested that the reason for the bifurcated review process was because Congress intended IPR to cut down on the “patents that shouldn’t have been issued in the first place.”

Companies that are frequent targets of patent suits, including large technology companies, such as Apple Inc. and Google Inc., have turned to IPR proceedings as a tactic in patent challenges. IPR is typically considered more efficient, both in terms of cost and time, than a federal court challenge.

The case before SCOTUS involves a patent owned by Cuozzo Speed Technologies LLC. The patent in question covers a speed-limit indicator. Cuozzo Speed Technologies LLC sued a number of companies including Garmin Ltd., General Motors Co. and TomTom NV. Garmin challenged the Cuozzo patent using the IPR procedure and the PTAB sided with Garmin, invalidating the Cuozzo patent on obviousness grounds. In turn, Cuozzo challenged the PTAB’s action in federal court, whereby the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) ultimately upheld the application of the BRI claim construction standard by the PTAB in the IPR proceedings.

The Supreme Court is expected to issue a ruling in late June of 2016.

Cuozzo Speed Technologies v. Lee

On Monday, April 25, 2016, the United States Supreme Court (SCOTUS) will hear oral arguments in Cuozzo Speed Technologies v. Lee. One of the most interesting issues in question involves the proper claim construction the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) should apply when analyzing the validity of patents in inter partes review (IPR) proceedings. The USPTO will determine whether the Federal Circuit erred in concluding that, in IPR proceedings, the PTAB may construe claims in an issued patent according to their “broadest reasonable interpretation” (BRI) rather than under a plain and ordinary meaning approach, which is applied by judicial courts when evaluating patent claim scope. The Court will also consider whether the the Director’s decision to institute an IPR in the first place is reviewable. Cuozzo Speed Technologies v. Lee represents the first opportunity by the USPTO to weigh in on the various administrative trial procedures put into effect by the America Invents Act (AIA) of September 16, 2012.

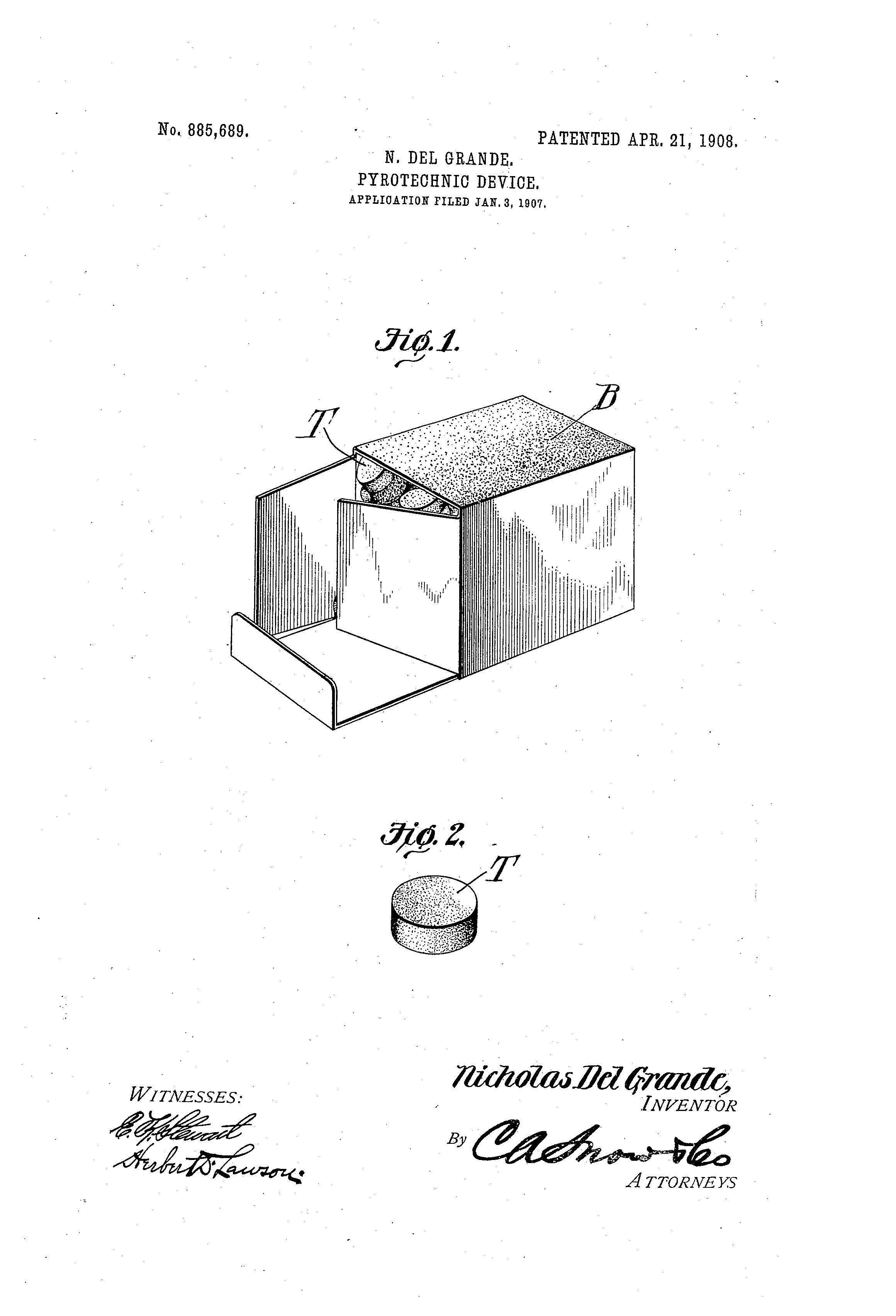

Patent of the Day: Pyrotechnic Device (Fireworks)

On this day in 1908 the patent for Pyrotechnic Device was granted, U.S. Patent No. 885,689.

NMotion 2016 Cohort

Suiter Swantz IP would like to congratulate the members of the 2016 NMotion cohort. Suiter Swantz IP will once again serve as a sponsor for NMotion and we are excited to meet all the new teams. This year's program will start on April 25th and end with demo day on July 26th. For more information about NMotion and this year's cohort visit http://www.nmotion.co/.

New Faces at Suiter Swantz IP

We are very excited to announce the addition of two new patent agents, Troy Anderson and Kazuya Toyama.

Troy holds a Ph.D. and a M.S. in Optics from CREOL, the College of Optics at the University of Central Florida, as well as a B.S. in Electrical Engineering from the University of Nebraska – Lincoln. Through graduate and post-graduate pursuits, he has developed a broad technical background in laser optics, geometric optics, spectroscopy, optical sensors, femtosecond laser systems, laser machining, materials science, surface science, electrochemistry, nanotechnology, image processing, electrical engineering, and metrology. Troy has also co-authored over 15 peer-reviewed journal publications and numerous technical conference presentations related to his research on tailoring material properties using femtosecond laser pulses.

Troy is registered to practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Kazuya (Kaz) obtained his B.S. in Chemistry from St. Francis College. While attending St. Francis, he researched tangential purification methods for Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) as a visiting researcher at Princeton University. Kaz obtained his Ph.D. in Chemistry from the University of Nebraska - Lincoln. His research focused on the development of new asymmetric catalysts and total synthesis of natural products. He gained hands on experience on a broad range of analytical instruments.

Prior to attending the University of Nebraska - Lincoln, Kaz worked as a research scientist with Bayer Chemical to improve polyurethane foam quality.

Kaz is registered to practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Smartphone Wars Apple v. Samsung

Since 2009, millions of dollars have been spent worldwide on litigating smartphone-related patent infringement cases in the “Smartphone Patent Wars.” The most well-known of these battles includes ongoing litigation between Apple, Inc. and Samsung Electronics Co., the latest verdict handed down on February 26th, 2016.

The term “patent war” describes a setting involving considerable litigation surrounding a given patented technology, particularly technology in a competitive and emerging field. Patent wars are not a new phenomenon – the first notable patent wars were the Sewing Machine Wars of the 1850s. In 1846, Elias Howe Jr. received Patent No. 4,750 for a sewing machine implementing the lockstitch design. Almost immediately Howe noticed seemingly infringing devices on store shelves. Howe attempted to license his patented technology to other sewing machine manufacturers, including Isaac Singer of Singer sewing machines. In cases where the manufacturer would not license his patent, Howe opted to file suit for infringement of his patent. Soon, other sewing machine manufacturers joined the action, until patent suits populated the dockets of multiple courts nationwide. Today, these trials might be considered the result of what is known as a “patent thicket”: an instance where patents have been issued to multiple entities for individual components of a single technology, creating a dense web of overlapping rights that forces manufacturers to license or infringe on one another to build a complete device.

Another instance of a patent war includes the controversy surrounding the telephone that occurred in the latter half of the 19th century. While Alexander Graham Bell is credited with the invention of the telephone (Patent No. 174,465), Bell was not the only person claiming inventorship of the telephone. Antonio Meucci and Daniel Drawbaugh both claimed to have invented the telephone before Bell, but lacked the financial resources to pay the application fee for a full patent. German inventor Johann Reis also claimed to be an inventor of the telephone, but never filed for patent protection. Credit could also be given to Elisha Gray, who alleged Bell was able to build a working model of a telephone (required by the Patent Office at the time) from information provided by Gray in the patent caveat. It is noted that Gray’s patent caveat and Bell’s application were filed on the same day, and that Bell submitted the working model nearly a month later. As Bell was able to build a working model before Gray, the associated patent rights ultimately were issued to Bell. Bell built a company around the telephone, a company that would be involved in dozens of patent suits and a considerable amount of telecommunications litigation throughout the 20th century.

Advancements in consumer usable electricity and the invention of the incandescent lightbulb also resulted in considerable litigation. Thomas Edison filed for his improvements to the light bulb in 1879 and received Patent No. 223,898 in 1880. This signaled the start of nearly a decade of litigation surrounding the light bulb. Edison was first sued for infringement by Joseph Swan for allegedly infringing Swan’s British patent—Swan and Edison settled the case and merged electric companies. In 1883, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) declared Edison’s 1880 patent to be based on the work of William Sawyer. Undeterred, Edison continued to argue his case and, in 1889, convinced the courts that his specific improvements on the light bulb, which relied on the use of a carbon filament, were patentable. These improvements are the basis for the first commercial incandescent bulb, and contributed to Edison’s widespread notoriety.

In addition to the above, patent wars have also been waged in fields including the radio, the “horseless carriage” or automobile, the airplane, the laser, and the personal computer, among many others

The Sewing Machine Wars of 1856 resulted in the first recognized patent pool of Howe, Singer, and two additional competitors, called the Sewing Machine Combination. A “patent pool,” which is a tool in navigating a patent thicket, involves multiple patent holders cross-licensing their individual parts of a single technology to one another to prevent issues with infringement. Notable patent pools include the Manufacturer’s Aircraft Association formed during World War I; patent pools for the video coding standards MPEG-2, MPEG-4 Part 2, and H.264; and the Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) Consortium in the early 2000s. Patent pools are not a perfect solution, providing a unique challenge to antitrust enforcement. Still, patent pools are a viable response to the increased possibility for infringement created by the ease with which knowledge is disseminated in the digital age.

Despite the viability of patent pools, patent wars still exist. The ongoing Smartphone Patent Wars litigation between Apple, Inc. and Samsung Electronics Co. includes contested technology within multiple generations of the iPhone, iPad, and Galaxy phone and tablet product lines, such as the “slide to unlock”, “pinch to zoom”, and “universal searching” features.

The first US jury trial between the two tech giants in August 2012 resulted in a $1.049 billion verdict for Apple. In December 2012, it was determined a miscalculating of damages occurred, and the amount owed was re-calculated to $959 million in November 2013. A partial judgment in December 2015 resulted in Samsung agreeing to pay Apple $548 million–with one caveat. Samsung reserved “the right to reclaim or obtain reimbursement” of the $548 million depending on the holding of the Supreme Court (who agreed on March 21, 2016 to hear the appeal). This will be the first design patent case heard by the Supreme Court in over a century.

In April 2014, Apple filed a second US suit claiming approximately $2 billion in damages, which resulted in a jury trial verdict of $120 million for Apple and a $160,000 verdict for Samsung. On February 26, 2016, the US Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit overturned the April 2014 verdict, invalidated two of the three contested Apple patents (including the “slide to unlock” feature), and found Apple to be infringing on one of Samsung’s patents – a major victory for Samsung in the US courts.

Another US jury trial involving Apple suing Samsung was docketed for March 28, 2016. Samsung filed for, and was granted, a stay of this trial when the Supreme Court agreed to hear the Samsung’s appeal regarding the 2015 judgment of $548 million.

With the February 26, 2016 verdict and the upcoming Supreme Court battle, one might consider how the Smartphone Patent Wars litigation has affected the disputed technology to date. Overturning the 2014 verdict involved litigating technology that is two “generations” old. Additionally, when the Supreme Court considers Samsung’s appeals it will be weighing in on technology that is at least five generations old. With those perspectives in mind, it seems likely that the Smartphone Patent Wars have had some adverse effect on the state of smartphone technology. On the other hand, it is difficult to quantify the amount of infringing activity that Apple was able stave off from other competitors due to Apple’s aggressive stance with Samsung. In essence, the aggressive stance Apple has taken with Samsung may communicate a “line in the sand” to other smartphone makers. It is also worth noting that as Apple filed suit after suit against Samsung, Samsung adjusted their UI technology so as to reduce the likelihood of future infringement, resulting in more diverse options for consumers. In addition, other companies in the smartphone space took efforts to release products with notable design differences from that of Apple’s protected products to ensure that they were not infringing on Apple’s patents.

Protecting an inventor’s right to exclude competitors from a particular technology space and incentivizing innovation represent the constitutional basis for awarding patents in the United States. While patent litigation helps to protect these goals of the US patent system, patent litigation may be harmful when in quantities that result in the designation of “patent war.” Using awarded patents as tools for continuous litigation in a patent war may stifle innovation, with time and money being spent on litigating the possibility of infringement instead of being spent on research and development.

On the other hand, the waging of a patent war by one company against another may aid in disincentivizing third party market entrants from infringing on the patent holders rights. Patent wars may also have beneficial uses for companies. A group of manufacturers locked in a patent war may decide to form a patent pool, combining their protected technologies and creating a product greater than the sum of its parts. A patent war may effectively control the amount of competition in a shared market.

The effectiveness of a patent war ultimately depends on the companies involved and their litigation and/or product development efforts. As the battlefields of the Smartphone Patent Wars quiet down, it will be interesting to see which companies benefited and which companies were harmed by their chosen product development and litigation tactics.

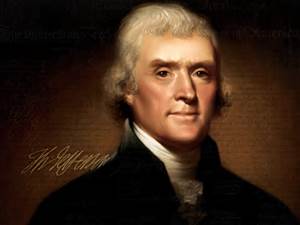

Thomas Jefferson's Birthday

Today is the birthday of Thomas Jefferson. While Thomas Jefferson is best known as the third president of the United States, one of the Founding Fathers and main authors of the Declaration of Independence, few people realize that he was also an inventor, the first administrator of the American patent system and one of the first patent examiners in the United States.

On April 10, 1790, President George Washington passed the first United States patent act, which provided inventors patent rights to their creations and paved the way for the modern American patent system. Under this act, the Department of State formed a patent board consisting of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of War Henry Knox, and Attorney General Edmund Randolph. The members of the patent board were tasked with administering the patent laws, whereby fees for a patent were set between $4 and $5 and the duration of a patent was set not to exceed 14 years. The new patent law gave the patent board the authority to grant patents to the inventor of “any useful art manufacture, engine, machine or device, or any improvement thereon not before known or used.” Board members were authorized to make such a grant of patent rights if it was found that “the invention or discovery [was] sufficiently useful and important.”

The very first patent granted by the board was issued on July 31, 1970 to Samuel Hopkins from Pittsford, Vermont. Hopkins’ invention was directed to improvements in "the making of Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new Apparatus and Process." 1 The patent was signed by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Attorney General Edmund Rudolph and President George Washington.

During that first year the patent act was passed, two more patents were granted by the board. Although the process was time consuming and arduous, the board members were proud of their work and recognized its importance to the Republic. After time passed, the volume of filings created by the new patent act soon became much more than the board members could handle. By 1791, Jefferson’s office took part in granting 33 patents. Jefferson quipped that the reviewing of patent applications was the most time-consuming of his various domestic responsibilities. By 1793, Jefferson and the other members of the board happily relinquished their burdensome patent examiner duties. The patent act of February 21, 1793 made the granting of patents almost an entirely automatic matter, with the three-man review board replaced by an administrative structure. It was not until 1802 when, then Secretary of State, James Madison formed the United States Patent Office, which established a more systematic patent-granting procedure. In 1836, the patent law was overhauled, creating a compromise between the strictness of Jefferson's review approach and the more liberal acceptance of all patent claims, which occurred during the intervening years. During his tenure, Jefferson is credited with establishing three criteria for a receiving a patent, which were adopted by the 1836 law and are still in effect today. In order to receive a patent, an inventor’s invention must be: new, non-obvious, and useful. The 1836 law is still largely in effect today. 2

Although Jefferson never held any patents himself, he was recognized for creating and/or improving many products and technologies such as a portable desk, the polygraph and the spherical sundial to name a few.

- http://www.uspto.gov/about-us/news-updates/us-patent-system-celebrates-212-years

- https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/patents

Big Omaha 2016 May 4- May 6

Several attorneys from Suiter Swantz IP will be attending Big Omaha 2016. Big Omaha is an annual conference that brings together entrepreneurs, founders, investors and emerging leaders. Big Omaha is held at KANEKO in the Omaha Old Market from May 4th to May 6th. To learn more about Big Omaha click here.

Heartland Student Entrepreneurship Conference 4/29/16

Matt Poulsen of Suiter Swantz IP will be a panelist at this year’s Heartland Student Entrepreneurship Conference. The panel of attorneys will outline many of the legal issues commonly faced by entrepreneurs.

Matt will discuss various intellectual property issues that startups and small business may encounter as they build their business.

For more information about the conference click here.

CLE: Intellectual Property Law Developments Seminar and Webinar 4/29/16