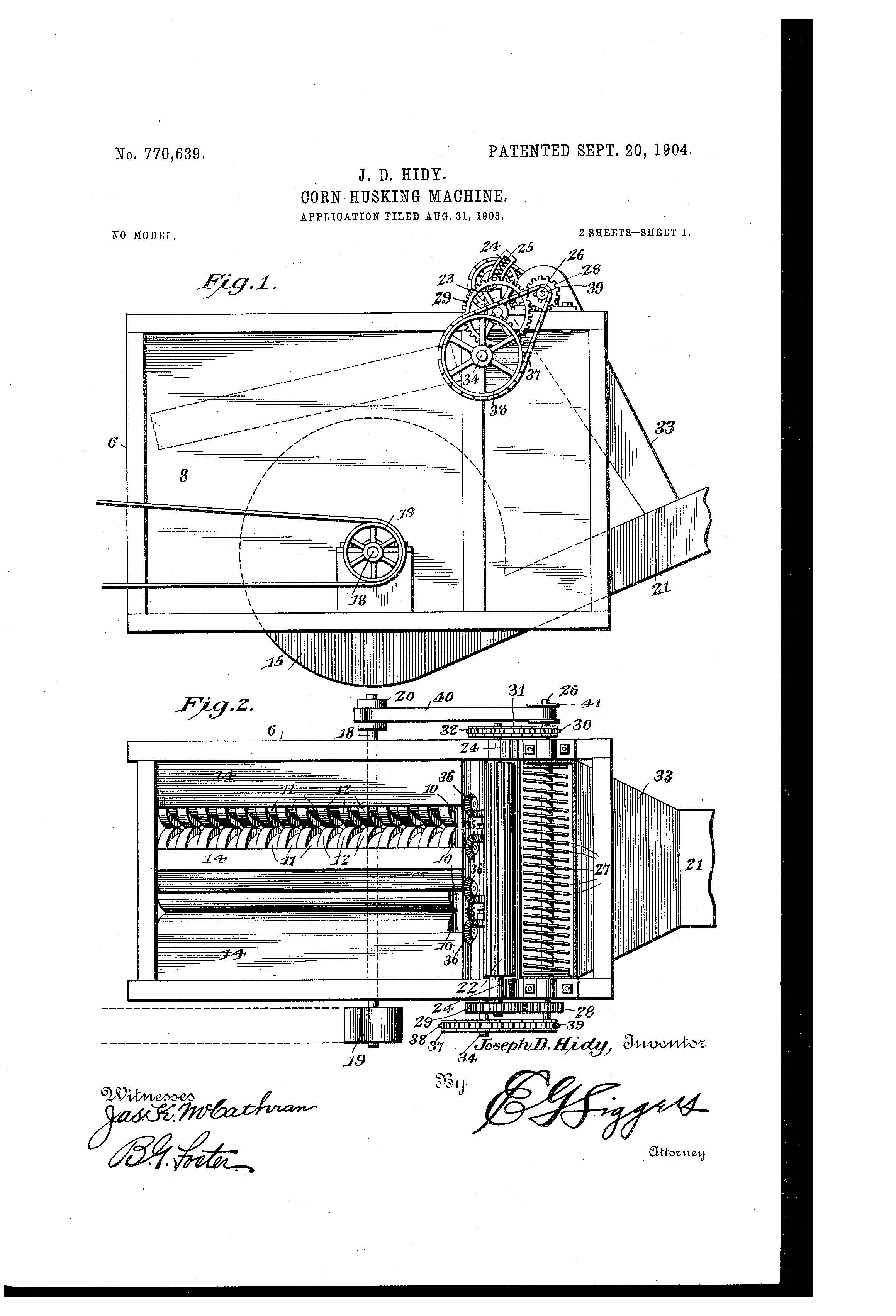

Patent of the Day: Corn Husking Machine

On this day in 1904 Joseph D. Hidy was granted the patent for CORN HUSKING MACHINE. U.S. Patent No. 770,639.

One object of the present invention is to provide mechanism which will thoroughly husk the corn and remove the silk therefrom without injuring the product, the ears passing over comparatively smooth surfaces, so that all projections and like objectionable features are obviated. This structure, moreover, is extremely simple, so that it may be manufactured at small cost.

Another object is to provide a husking-machine of the above nature that will operate rapidly without decreasing its efficiency.

A still further object is to provide shredding means in connection with the husker and to so construct the discharge from the husking mechanism that it will so constitute means for removing the shredded material.

CAFC Issues Decision in McRo, Inc. v. Bandai Namco

On September 13, 2016, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) issued a decision in the highly anticipated case McRo, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America. The decision found that the software patent claims at issue from U.S. Patent Nos. 6,307,576 and 6,611,278 are patent eligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

This case originated in a District Court in Delaware and was transferred and consolidated to the United States District Court for the Central District of California. The claims in question relate to methods for automatically animating lip synchronization and facial expression of animated characters. After holding a Markman hearing - a pretrial hearing in a U.S. District Court where a judge examines evidence from all parties on appropriate meanings of relevant key words used in a patent claim, when a plaintiff alleges infringement - the District Court granted the Defendant’s motion that all asserted claims were unpatentable. Originally the Court did not believe the claims to be directed at an abstract idea, but later determined the claims too broad and not limited to a specific set of rules, which in the eyes of the District Court meant, they were abstract ideas.

As set forth by the Supreme Court in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank, compliance with § 101 requires the use of a two-step test to determine whether claims are patent eligible. First, one must determine if the claim at issue is directed to an abstract idea, a judicial exception, a law of nature, or a natural phenomenon. If so, the claims are then directed to the second step where one must then identify elements showing an inventive concept; whether any element or combination of elements, in the claim is sufficient to ensure that the claim amounts to significantly more than the judicial exception.

After the test was applied, the District Court found "while the patents do not preempt the field of automatic lip synchronization for computer-generated 3D animation, they do preempt the field of such lip synchronization using a rules-based morph target approach" and that "novel portions of [the] invention are claimed too broadly." Thus, the District Court believed the claims failed to meet § 101 requirements.

Notably, the CAFC did not side with the District Court's conclusion that the claims are "drawn to the [abstract] idea of automated rules-based use of morph targets and delta sets for lip-synchronized three-dimensional animation." The CAFC criticized this characterization and went on to point out that the claims "define a morph weight set stream as a function of phoneme sequence and times associated with said phoneme sequence" and "require applying said first set of rules to each sub-sequence . . . of timed phonemes." The CAFC implied that the District Court had improperly ignored these elements stating “We have previously cautioned that courts ‘must be careful to avoid oversimplifying the claims’ by looking at them generally and failing to account for the specific requirements of the claims.”

In a concluding paragraph, Judge Reyan wrote:

When looked at as a whole, claim 1 is directed to a patentable, technological improvement over the existing, manual 3-D animation techniques. The claim uses the limited rules in a process specifically designed to achieve an improved technological result in conventional industry practice. Alice, 134 S. Ct. at 2358 (citing Diehr, 450 U.S. at 177). Claim 1 of the ’576 patent, therefore, is not directed to an abstract idea.

The CAFC concluded:

Claim 1 is not directed to an abstract idea and recites subject matter as a patentable process under § 101. Accordingly, we reverse and hold that claims 1, 7–9, and 13 of the ’576 patent and claims 1–4, 6, 9, 13, and 15–17 of the ’278 patent are patentable under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

The CAFC’s ruling has brought clarification to the muddled interpretation of § 101 and highlighted pertinent information to aid future cases through the murky waters of § 101.

Patent of the Day: Magneto Electric Machine

On this day in 1882 Thomas Edison was granted the patent for Magneto Electric Machine. U.S. Patent No. 264,643.

In this machine Edison employs a cylinder the surface of which is covered with a coil of wire wound around it lengthwise and parallel to the axis of rotation. The electric current, passing through the coil, converts the cylinder into a magnet. One side of the cylinder is of north polarity and the opposite side is of south polarity. A shell of iron is employed, within which this magnetic cylinder is revolved, and by induction the shell becomes magnetized. Hence the magnetic forces in the shell revolve around the same in harmony with the revolving magnetic cylinder.

There is a space between the revolving magnetic cylinder and the inside of the shell, within which space there are longitudinal wires connected in a peculiar manner to the commutator, and in the wires an induced current is set up in consequence of the revolving magnetic forces crossing and cutting these wires as the magnetic cylinder revolves within the shell, and trout the commutator the current is taken to the line-wires.

How Certain is “Reasonable Certainty” Under Nautilus?

Indefiniteness finds statutory basis in 35 U.S.C. § 112 (b), which states that a “…specification shall conclude with one or more claims particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter which the inventor or a joint inventor regards as the invention.” This statutory basis is fleshed out by precedential court decisions. For example, courts have said that the statutory requirement of particularity and distinctness is met only when claims clearly distinguish what is claimed from what went before in the art, and clearly circumscribe what is foreclosed from future enterprise.

Because an issued patent’s validity may be challenged based on the definiteness or indefiniteness of the issued claims, indefiniteness must be avoided by drafting attorneys and agents, considered by patent valuators, and discovered by patent litigators.

In this regard, on August 28, 2015, in Dow Chemical Co. v. Nova Chemicals Corp., 803 F.3d 620 (2015) (“Dow II”), the Federal Circuit overturned an earlier decision it had made January 24, 2012, regarding indefiniteness. In its earlier decision, the Federal Circuit cites to Enzo Biochem, Inc., and stated that indefiniteness does not require exactness, but allows for some experimentation to resolve the meaning of claim terms. (See, Enzo Biochem, Inc. v. Applera Corp., 599 F.3d 1325, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2010), cert. denied, 131 S. Ct. 3020 (2011)). Although Dow’s disclosure did not disclose any stress-strain curves, and did not specify exactly how to calculate a slope, expert testimony was received, indicating that a person skilled in the art could calculate the slope of the SHC with a little experimentation. Thus, the claims were not held to be indefinite. As stated above, Dow II overturned this earlier decision based on the interim decision by the Supreme Court in Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 572 U.S. ___, 134 S. Ct. 2120 (2014), which changed the standard for indefiniteness.

The previous standard for indefiniteness stated that claims should be “…amenable to construction, however difficult that task may be. If a claim is insolubly ambiguous, and no narrowing construction can properly be adopted,…the claim [is] indefinite.” Exxon Research & Engineering Co. v. United States, 265 F.3d 1371, 1375 (Fed.Cir.2001). The Nautilus standard states that “…a patent is invalid for indefiniteness if its claims, read in light of the specification delineating the patent, and the prosecution history, fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention." Nautilus, 134 S.Ct. at 2124. Under the old standard, the Federal Circuit determined Dow Chem.’s claims to be definite; however, under the new standard, Dow Chem.’s claims were found to be indefinite. Such a result seems to suggest that the newer standard constitutes a higher degree of scrutiny than the old standard, and therefore necessitated the invalidating of Dow Chem.’s claims.

Despite the appearance of the higher degree of scrutiny, in a non-precedential case, the Federal Circuit seems to indicate the exact opposite. The case is Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Zoll Medical Corp., 2014-1764, 2014-1791 (Fed. Cir. Jul. 28, 2016). At the district court level, a jury instruction was given prior to the Nautilus decision, reciting the “insolubly ambiguous” standard as the standard for determining definite or indefinite claims. Under those instructions, the jury found the claims to be definite and awarded damages to Zoll Medical Corp. On appeal, the Federal Circuit said the following with respect to whether the now outdated instructions affected prejudice towards Phillips, the appellant:

“We conclude that it did. While we have not clarified the relationship between "insolubly ambiguous" and "reasonably certain, " it must be admitted that the "insolubly ambiguous" standard is a harder threshold to meet than the post-Nautilus standard. Thus, if the jury actually applied the "insolubly ambiguous" standard, then it would be fair to conclude that the jury instructions prejudiced Philips, especially in light of the extensive case on indefiniteness that Philips presented-even though not sufficient to merit JMOL.” (Emphasis added).

Albeit in dicta in a non-precedential case, the Federal Circuit indicates that the new, post-Nautilus standard is a lower threshold for indefiniteness than the “insolubly ambiguous” standard. Due to the diverging indications given in Dow II and Koninklijke Philips, one must ask, ‘how certain is the reasonably certain standard that Nautilus sets forth?’ It appears that there is still room for clarification from the Federal Circuit. However, since Dow II first indicated that the Nautilus standard may be a higher threshold, cases decided after Dow II may be a good litmus for determining what we actually do know about indefiniteness.

The following is a brief summary of what we do know:

-The plain meaning of a term may lend credence to the definiteness of claims. Cioffi v. Google, Inc., 2015-1194, non-precedential, citing Ancora Techs., Inc., v. Apple, Inc., 744 F.3d 732 (Fed. Cir. 2014); see also, SimpleAir, Inc. v. Sony Ericsson Mobile Communications AB, 118 U.S.P.Q.2d 1451, 820 F.3d 419 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

-One cannot have both apparatus and method or functional language in one claim unless the apparatus claim is clearly limited to an apparatus having the recited structure and capable of performing the recited functions. UltimatePointer, L.L.C. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd., 118 U.S.P.Q.2d 1125, 816 F.3d 816 (Cir. 2016).

-If a claim term has no generally recognized meaning, it may be construed under §112, sixth paragraph, and is likely indefinite if its language “…might mean several different things and no informed and confident choice is available among the contending definitions.” Media Rights Technologies, Inc. v. Capital One Financial Corporation, 116 U.S.P.Q.2d 1144, 800 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

-Terms of degree may be scrutinized more heavily under the post-Nautilus standard as compared to the “insolubly ambiguous” standard. Liberty Ammunition, Inc. v. United States, 2015-5057, 2015-5061 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (citing Interval Licensing LLC v. AOL, Inc., 766 F.3d 1364, 1370-71 (Fed. Cir. 2014), cert, denied, 136 S.Ct. 59 (2015)).

-Factual determinations used to reach the ultimate determination of indefiniteness are reviewed for clear error. Icon Health & Fitness, Inc. v. Polar Electro Oy, 2015-1891, 2016-1166 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (citing Teva Pharm. USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 135 S. Ct. 831, 842 (2015)). In this case, claims are upheld as invalid for indefiniteness after hearing expert testimony and extrinsic evidence. For an example of claims that are upheld as definite after hearing expert testimony and extrinsic evidence, see Akzo Nobel Coatings, Inc. v. Dow Chem. Co., 811 F.3d 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

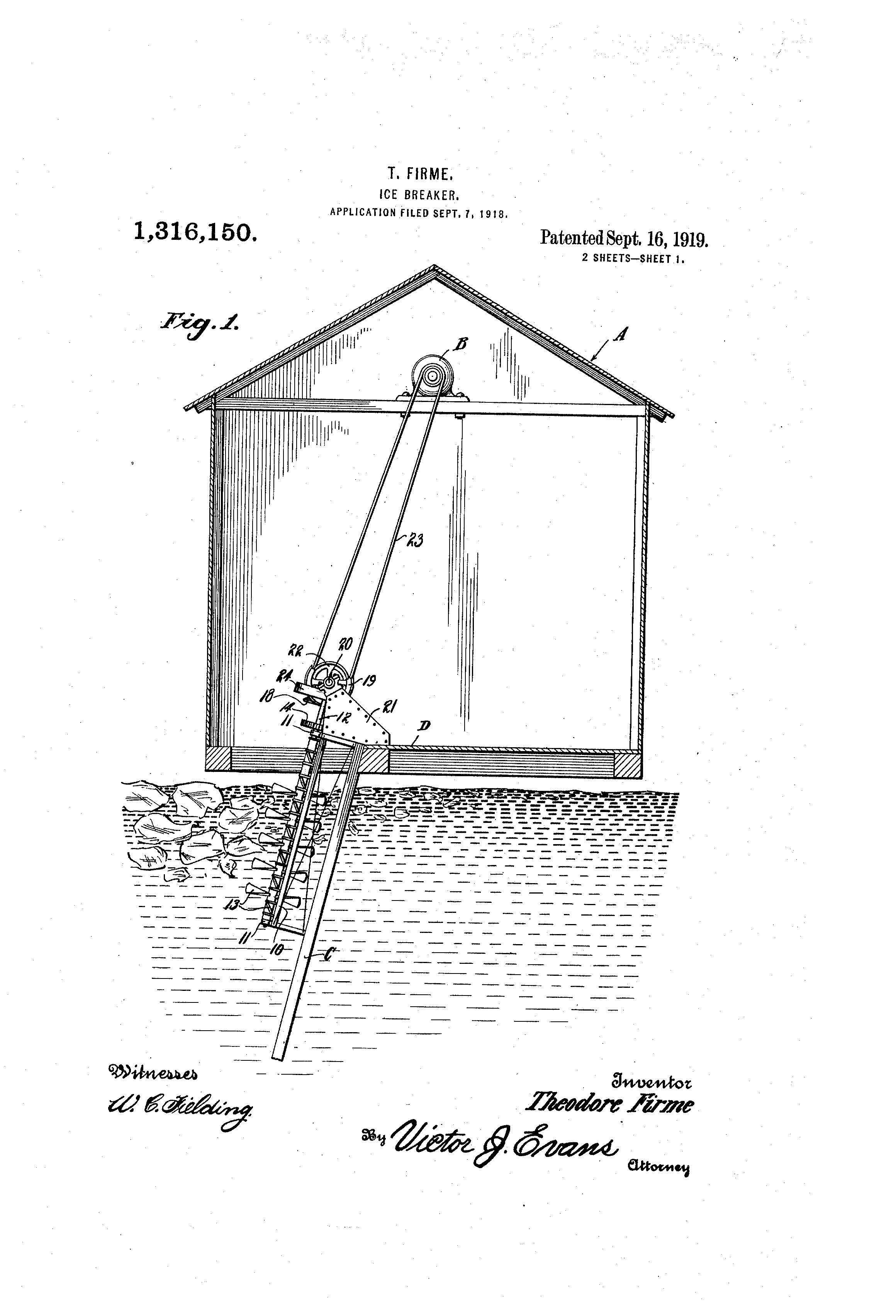

Patent of the Day: Ice Breaker

On this day in 1919 Theodore Firme was granted the patent for ICE BREAKER. U.S. Patent No. 1,316,150.

Considerable trouble and expense at water-power plants is occasioned by the flume grates being clogged with large pieces of anchor ice, which often results on shutting down the plants for the purposes of clearing the grates. This is usually done by clearing the ice from the top of the grates by hand, the process being so slow that much time is lost by this operation.

The present invention aims to overcome these difficulties by providing a device located at the entrance of the flumes which will crush or break the ice into small pieces and direct them to the top of the water passing through the flume, where they may be removed if desired.

More specifically stated, the invention includes a plurality of spaced propeller blades located at the entrance of the flume in advance of the grate, so as to prevent the ice from reaching the said grate, the blades being so arranged as to direct the broken ice upward to the surface of the water.

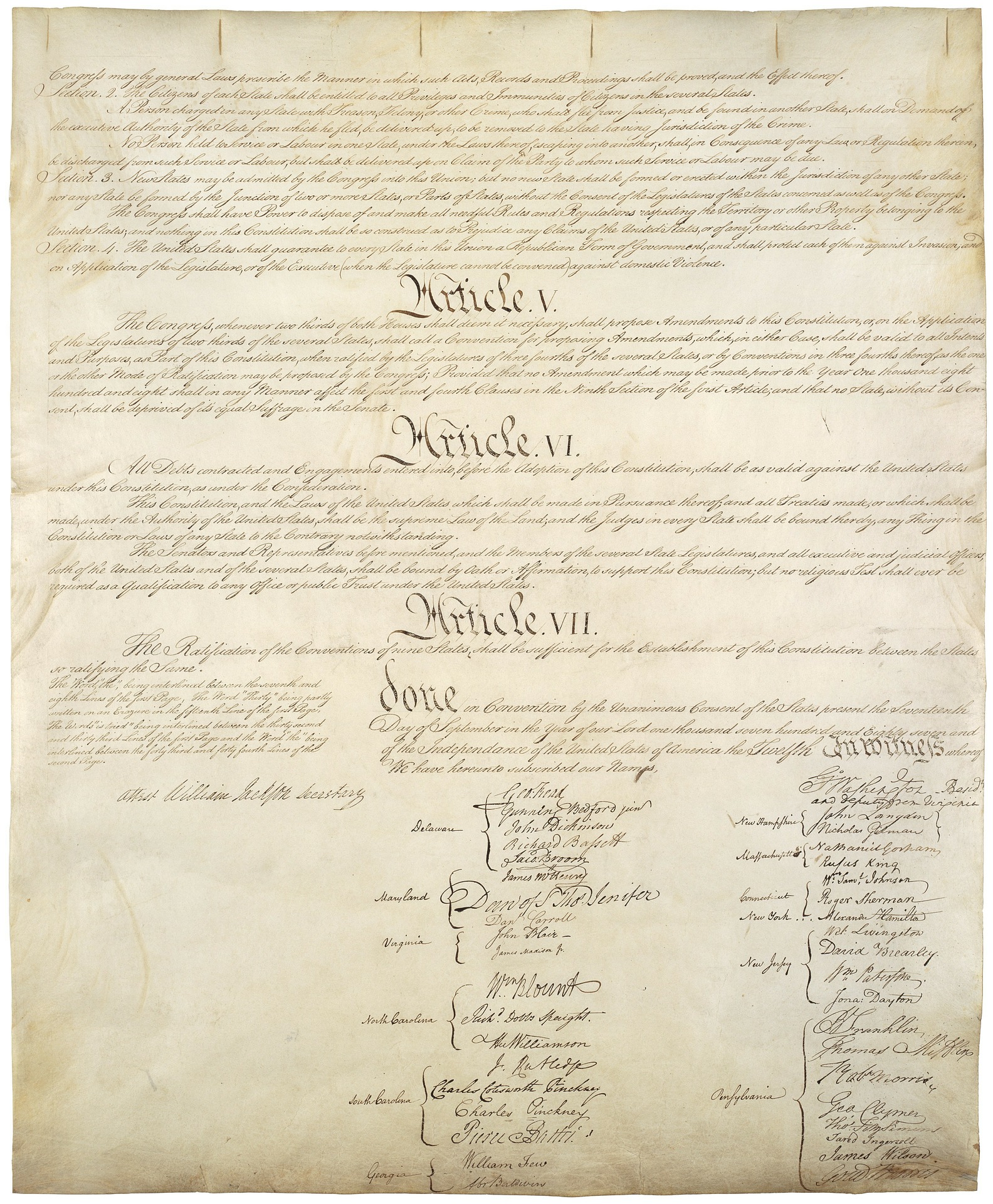

The United States Constitution and Intellectual Property

With Constitution Day and Citizenship Day just around the corner, it is apropos to reflect on the Founding Fathers, the adoption of the United States Constitution (September 17, 1787), and intellectual property rights.

At the time of Constitutional Convention in 1787, most of the thirteen states had copyright laws in effect. The laws varied from state to state; they were not standardized across the country. The adoption of copyright laws by individual states had been provided for in the Articles of Confederation. There were no federal laws pertaining to intellectual property because under the Articles of Confederation, the Continental Congress did not have the power to pass national legislation. During the Constitutional Convention, James Madison and Charles Pinckney submitted separate proposals pertaining to intellectual property rights to be included in the United States Constitution.

Madison proposed that Congress have the power “to secure to literary authors their copyrights for a limited time” and Pinckney proposed Congressional power “to secure to authors exclusive rights for a limited time.” The proposals were referred to the Committee on Detail for discussion which resulted in the Committee’s proposal for the current clause known as the Copyright Clause (or Copyright and Patent Clause). The clause provides Congress the power to issue patents and copyrights:

Congress shall have Power… To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.... Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution

Thomas Jefferson, as Secretary of State, was a member of the first Patent Board, along with Henry Knox, Secretary of War, and Edmund Randolph, Attorney General. Jefferson is considered to be the first administrator of the American patent system and the first patent examiner. At the time of the Constitutional Convention, Jefferson was the ambassador to France and could not attend the convention. In 1787, Jefferson was cautious about granting patents and copyrights because he saw them as a form of a monopoly. By 1789, his opinion had softened somewhat and he wrote to James Madison recommending an article be added to the Bill of Rights with term limits on intellectual property rights: “Monopolies may be allowed to persons for their own productions in literature, and their own inventions in the arts, for a term not exceeding __ years, but for no longer term, and no other purpose..."

Although prolific inventors and writers themselves, Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson never sought patents for any of their work. In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin wrote, “As we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously.”

George Washington was a strong proponent for a patent system. In his first Annual Message to a Joint Session of Congress, he urged Congress to pass legislation on patents and copyrights. A few months later, the Patent Act of 1790 was signed into law on April 10, 1790, followed by the Copyright Act of 1790 signed into law on May 31, 1790. Washington signed the first United States issued patent on July 31, 1790, (U.S. Patent No. 1), granted to Samuel Hopkins for an improvement "in the making of Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new Apparatus and Process.”

It has been over 200 years since the signing of the United States Constitution and the first copyright and patent laws. Although there have been numerous changes in the laws and the patent system, the central concepts remain the same.

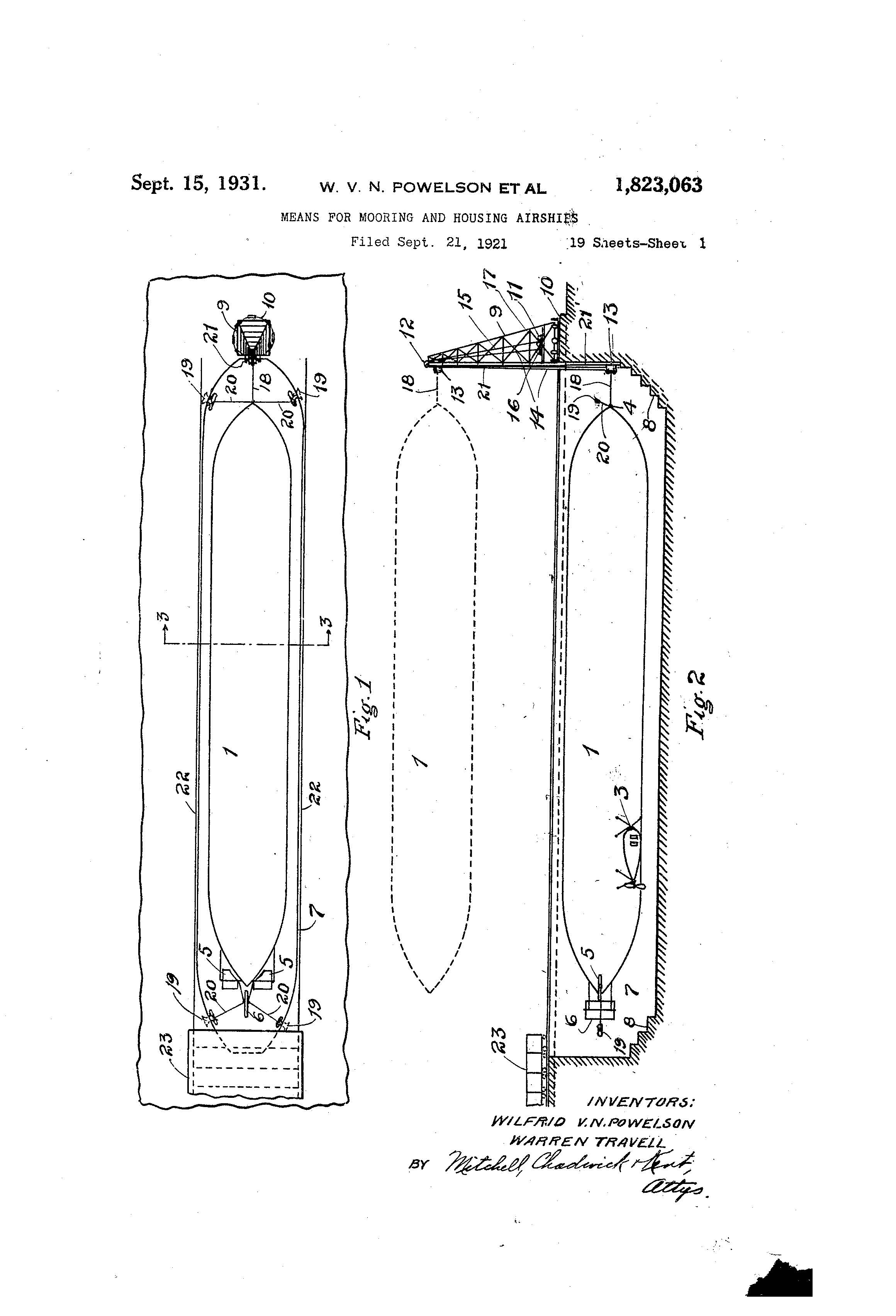

Patent of the Day: Means for Mooring and Housing Airships

On this day in 1931 Wilfrid V. N. Powelson and Warren Travel were granted the patent for MEANS FOR MOORING AND HOUSING AIRSHIPS. U.S. Patent No. 1,823,063.

According to present practice, airships are housed in large buildings, called hangars, erected above the surface of the ground. Airships are moved into and out of these hangars by hand, through large doorways or openings the ends, requiring a very large number of men for the larger airships. Accidents to airships in entering and leaving these hangars are not infrequent, due to the inability of human hands to hold the airships securely in position, by reason of the very great forces that are frequently applied to the surface of the airship by the wind. All hangars at present in use have a very large cubic capacity as compared with the cubic capacity of the airship; also hangars built to accommodate an airship of a given size may not be increased to accommodate a larger airship without practically destroying the building.

It is the object of this invention to provide housing facilities which are free from the above mentioned defects. The inventors propose to construct an airship shelter preferably either wholly or partly under ground, conforming to the shape of the airship, and providing opportunities for inspection and repair that are not available in any type of hangar now known to the art, into and from which the airship is moved vertically under mechanical control, with freedom from the dangers heretofore incident to entrance and exit.

How Do You Like Them Apples - Enough to Patent Them?

It is apple-picking season! That time of year where apple orchards are busy with people buying baskets of red, green, and yellow fruits. Did you know that some of your favorite apple varieties may have intellectual property protection?

A sometimes forgotten and less talked about type of patent is the plant patent. According to the USPTO, “a plant patent is granted by the Government to an inventor (or the inventor's heirs or assigns) who has invented or discovered and asexually reproduced a distinct and new variety of plant, other than a tuber propagated plant or a plant found in an uncultivated state. The grant, which lasts for 20 years from the date of filing the application, protects the inventor's right to exclude others from asexually reproducing, selling, or using the plant so reproduced.”¹

Plant patents came about in the early 1930’s. The first plant patent was granted in 1931 to Henry Bosenberg for a CLIMBING OR TRAILING ROSE (USPP1 P). Since then thousands of plant patents have been granted including several patents granted to different varieties of apples. In fact, in recent years, there have been some interesting trends in apple intellectual property.

For instance, in the late 1980’s, the University of Minnesota produced and patented the HONEYCRISP apple variety (USPP7197 P). Researchers cross-pollinated different apple trees, making new genetic combinations, and selected this one as one to produce. The Honeycrisp blossomed in popularity among consumers. Although the Honeycrisp variety was patented, anyone who wanted to could plant a Honeycrisp tree. Nurseries would sell the trees to anyone who called and ordered one, but since it was patented, growers would have to pay a royalty to the University of Minnesota. The royalty fee amount to approximately one dollar per tree, and since then, the patent has expired.

A few years ago, the University of Minnesota developed another tree called the MINNEISKA (USPP18815 P3), which produces the SweeTango® apple. The SweeTango variety has been much more controlled than its Honeycrisp predecessor. Only a small group of apple growers has been given license to grow this variety of apple. The SweeTango is also covered by several trademark registrations. Therefore, anyone who tries to sell an apple under that name could face a trademark dispute. Royalties are also paid to the University of Minnesota for the SweeTango apples that are sold.

The Minneiska, for example, is now known as a “club” or “managed” variety. There are many apple varieties that are controlled like this currently available in stores. These types of apples are only allowed to be produced by a particular group of members. The push to produce club varieties and safeguard them through patent and trademark protection has changed the landscape of how these products are sold. Many people in the apple industry are now putting money into marketing and selling their produce, knowing that with their intellectual property rights protected, not just anyone can sell the same product. Intellectual property protection also helps with quality control and serves to control the quantity of apples that are produced.

When you bite into one of those juicy apples, think, you might just be taking a bite out of someone’s intellectual property.

Office Hours September 29 at the Omaha Startup Collaborative

Suiter Swantz IP will be holding office hours September 29th at the Omaha Startup Collaborative, located in the Exchange Building in downtown Omaha.

Chad Swantz will be there from 3:00 - 5:00pm. Feel free to send Chad an email (cws@suiter.com) if you’d like to reserve a time slot or have any questions. In addition, meeting times can always be made on an as-needed basis.

Suiter Swantz IP

402-496-0300

www.suiter.com

Attorneys Matt Poulsen & Nick Grennan selected as "Rising Stars" for 2016

Suiter Swantz IP is proud to announce that attorneys Matt Poulsen and Nick Grennan have been selected as “Rising Stars” for 2016 by Super Lawyers. Super Lawyers is a research-driven, peer-influenced rating service of outstanding lawyers who have attained a high degree of professional achievement and peer recognition. Congrats Matt and Nick!

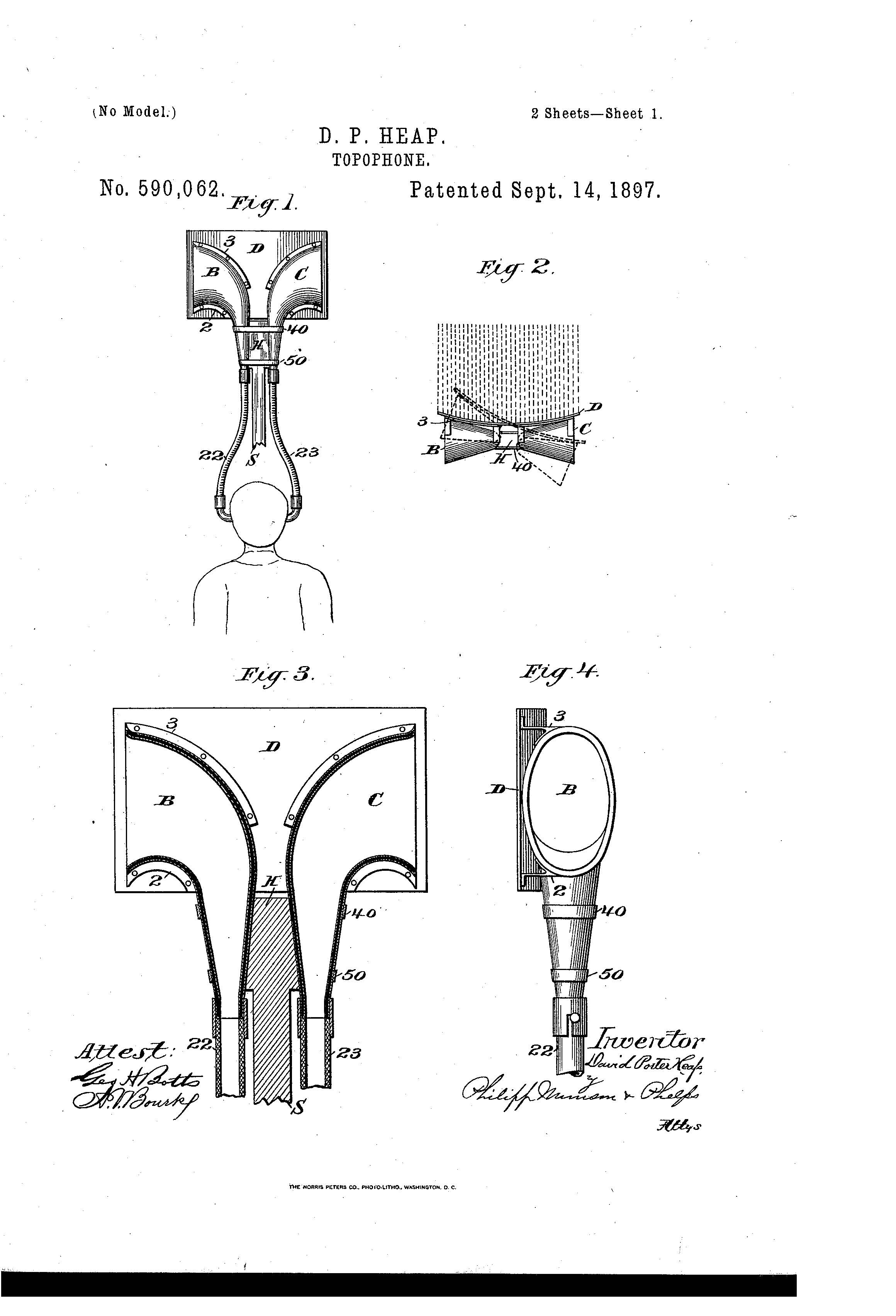

Patent of the Day: Topophone

On this day in 1887 David Porter Heap was granted the patent fr TOPOPHONE. U.S. Patent No. 590,062.

The principal purpose of this invention is to enable vessels to change their direction of movement with relation to dangerous objects, such as vessels, icebergs, the shore, or similar obstacles to their safe movement, and thus avoid contact or collision with them, which purpose is attained by means of an instrument whereby the direction or source of sounds produced at or reflected from a more or less distant point from the instrument may be determined in time to enable the vessel to escape, if necessary, any danger the source of the sound may offer. The usefulness of this instrument is especially realized by its employment as an aid to navigation, its operation in such use being to detect and locate the direction or position of a sound-producing object in its relation to a vessel at such times when said object may not be visually perceived, as at night, during foggy weather, or by reason of distance; but the instrument is susceptible of other uses, as during a war, when it is desirable to ascertain the location of an approaching body of men or the position of a dangerous cannon and the like when the same are not visible.

Office Hours September 15 at the Omaha Startup Collaborative

Suiter Swantz IP will be holding office hours September 15th at the Omaha Startup Collaborative, located in the Exchange Building in downtown Omaha.

Matt Poulsen will be there from 1:00 - 4:00 pm. Feel free to send Matt an email (map@suiter.com) if you’d like to reserve a time slot or have any questions. In addition, meeting times can always be made on an as-needed basis.

Suiter Swantz IP

402-496-0300

www.suiter.com