NCAA Football, the College Football Playoff, and…Patents?

The debate had been played out by hundreds of people, across thousands of bars and homes, a million times over: should the college football post-season move from a bowl system to a playoff system? Invariably, the college football playoff debate included many of the same arguments: determination of a single champion, elimination of conference bias, valuation of conference championships, inclusion of worthy teams, and concern for the number of games in the season, among other arguments. Finally, in 2014, college football fans rejoiced as the college football post-season transitioned from the old Bowl Championship Series (BCS) to the new College Football Playoff (CFP) we have come to enjoy today. Overall, the CFP has been met with overwhelming support and success. This incredible success begs the question: why wasn’t the transition to a playoff system made sooner?

The answer to this question may come from an unlikely source: the U.S. patent system. It is widely understood that patents in the United States and abroad are obtained by inventors to capitalize on their ideas and inventions. Utility patents are frequently obtained by companies like Apple and Ford Motors to protect ideas such as software, mechanical systems, and methods of producing equipment. However, it may come as a surprise to many that even methods of playing a board game may be patented. For example, U.S. Patent No. 2,026,082 entitled “Board Game Apparatus,” is the underlying patent for the popular board game Monopoly. Similar games and methods of playing games have been patented over the years, including U.S. Patent No. 5,226,655 entitled “Apparatus and Method of Playing a Board Game Simulating Horse Racing and Wagering,” and U.S. Patent No. 3,454,279 entitled “Apparatus for Playing a Game Wherein the Players Constitute the Game Pieces,” the underlying patent for the game of “Twister.”

Returning to the questions at hand, the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) may not have been able to implement a college football playoff sooner because it had already been patented. U.S. Patent No. 6,053,823 entitled “Method for Conducting Championship Playoff” could have been one of the roadblocks standing between the bowl system and a championship playoff. Broadly, the patent is directed to “methods for conducting a series of sporting events” and, more particularly, to “an improved method for conducting a championship football tournament.”

What is even more interesting is that the patent specifically contemplates a championship playoff for NCAA Division I football. Furthermore, the issued patent incorporates many of the same elements which make up the current college football playoff system. Following a regular season of eleven games, teams would be ranked by a “poll configuration,” including two major polls: (1) a coaches’ poll, and (2) a writers’ poll, which may be subjective and/or objective. A weighted formula, which takes into account both the coaches’ poll, the writers’ poll, and a third independent poll would determine final regular season rankings. After teams are ranked, a championship playoff tournament would be created. Teams would play in a March-Madness-style knockout tournament until a champion was determined around New Year’s Day. Sound familiar?

To add to the intrigue, Mark Cuban, noted Texas billionaire, sports fanatic, and owner of the Dallas Mavericks, had long been a proponent of transitioning college football to a playoff format. In 2010, Cuban started a blog, formed playoff proposals, lobbied NCAA athletic directors, and even founded a company named Radical Football in an attempt to move to a playoff format. However, in a blog post dated December 17, 2010, Cuban revealed he received an anonymous letter advising him to tread lightly in attempting to form a college football playoff. In addition to advising Cuban not to “waste your money,” the letter informed him that “the playoffs are already owned by someone, as in, the patent for resolving the FBS championship by way of a playoff was issued long ago. It's called a method patent, so be careful not to infringe it.”

Was this patent one of the reasons why a college football playoff took so long to implement? If so, what role did the patent have in shaping the college football playoff landscape we have come to know? The answers to these questions are still unclear. However, one thing is clear; those in favor of expanding the current college football playoff may cite U.S. Patent No. 6,053,823 as a source, as even the original patent for a college football playoff clearly states that a twelve-team playoff would be ideal!

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm, based in Omaha, NE, serving all of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. If you have any intellectual property questions or need assistance with any patent, trademark, or copyright matters and would like to speak with one of our patent attorneys, please contact us.

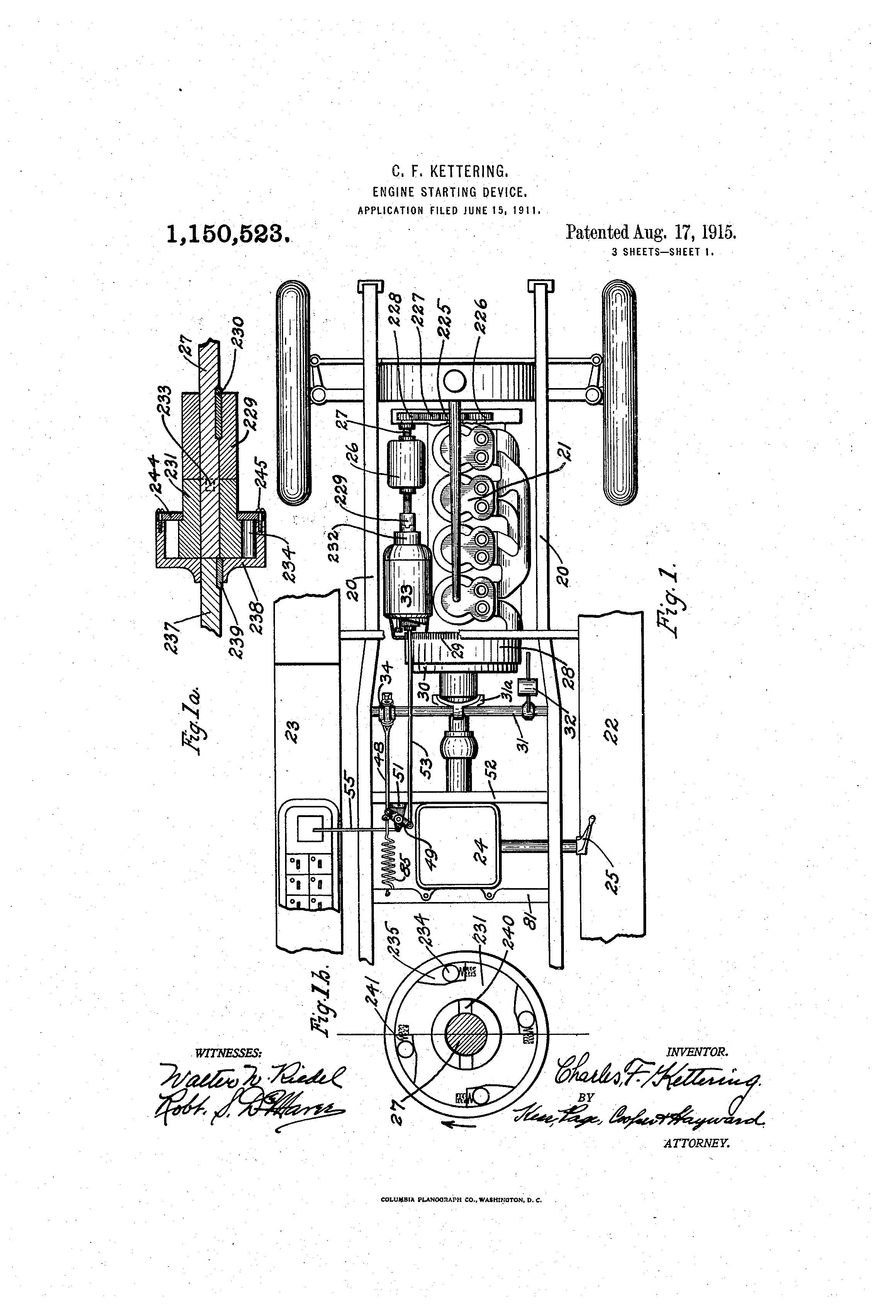

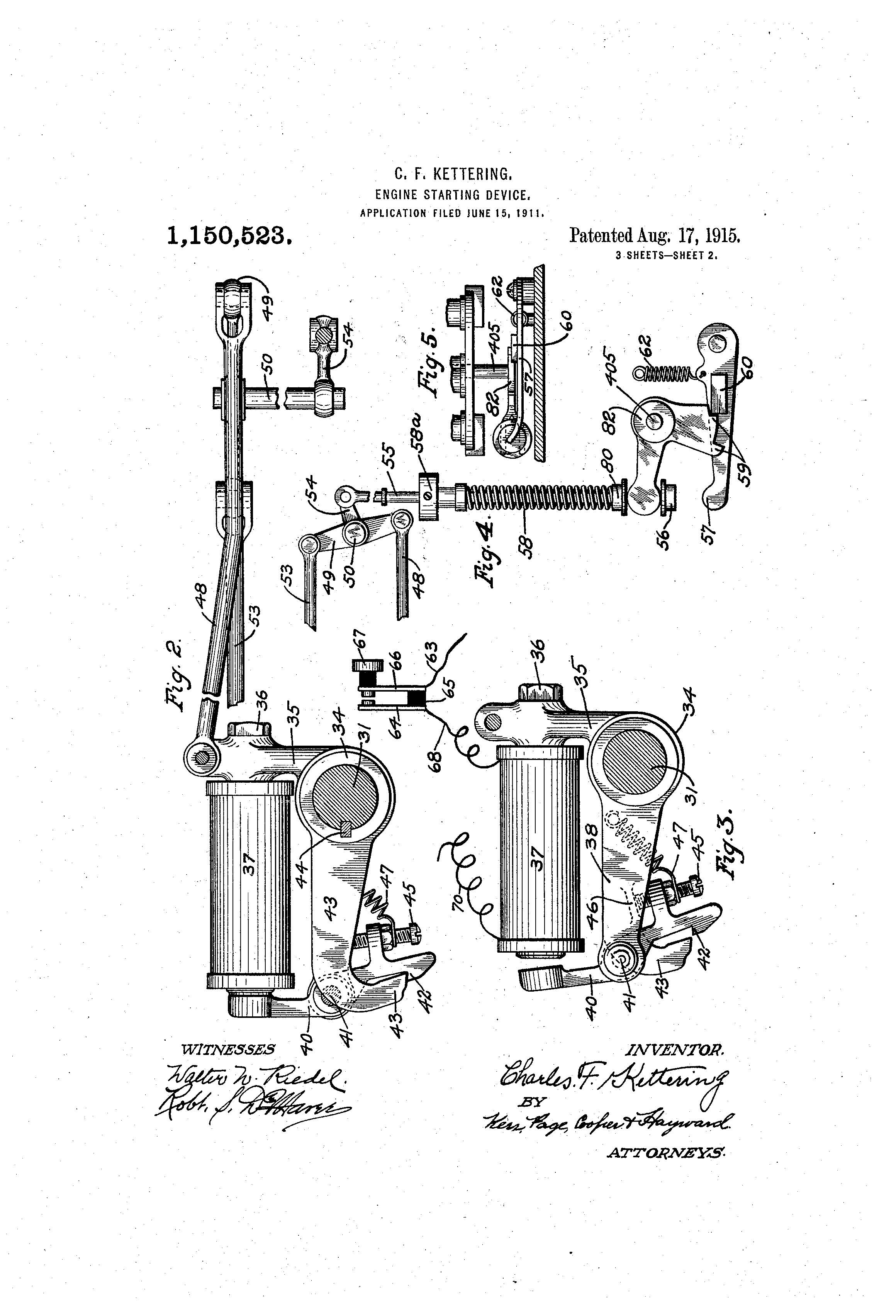

Patent History: Engine Starting Device

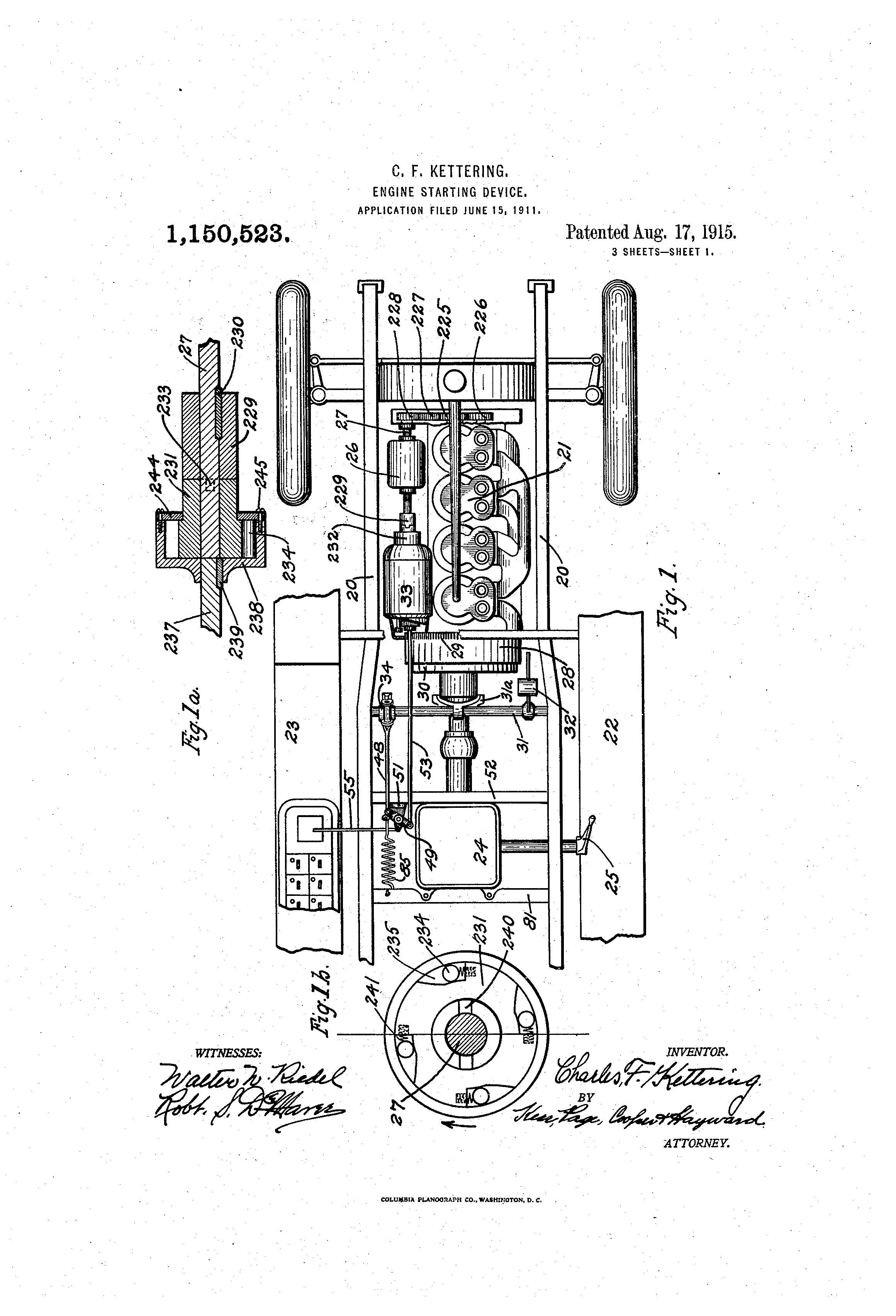

On August 17, 1915, Charles Kettering was granted the patent for “Engine Starting Device”, U.S Patent No. 1,150,523.

Charles F. Kettering was born on August 29, 1876, in Loudonville, Ohio. After graduating high school, Kettering became a teacher. Students were engaged by his science demonstrations that included electricity, heat, magnetism, and gravity. He took some college classes at the College of Wooster but due to his poor eyesight, he was forced to drop out. He later transferred to Ohio State but was forced to drop out again due to his eyesight. He got a job as a foreman of a telephone line crew. He found ways to practically use his electrical engineering skills. Eventually, Kettering found proper glasses, returned to OSU, and graduated in 1904 with an electrical engineering degree.

After graduation, OSU recommended Kettering to the National Cash Register, a research laboratory in Dayton, Ohio. There he invented an easy credit approval system and the electric cash register. He deemed himself a practical inventor, often hanging around the sales team because “they had some real notion of what people wanted”.

In 1909, he and colleague Edward Deeds founded the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, also known as Delco. Prior to starting Delco, the two worked on automobile ignitions, specifically, high-energy spark ignitions. The advancements they made with the ignition sparked the idea of starting the company. Their goal was to enter the field of automobiles with their improved ignition.

Before the electric self-starting engine, drivers had to go to the front of their car and turn a hand crank to start the engine. This was at times dangerous and caused injury. In 1908, a close friend of Henry Leland, the Chief at Cadillac, died due to complications when an automobile crank broke his jaw. Leland’s engineers worked on an electric self-starter but their device was not practical due to its large size. Leland called Kettering and asked for his help.

The engineers at Delco worked around the clock to improve the engine Kettering and Deeds initially developed. They eventually came up with the Engine Starting Device. It had three purposes: starter, generator, and spark production for ignition and a current for lighting. It was placed in the 1912 Cadillac model and soon, other car companies began to use this new type of engine.

This invention relates to a system of devices for use in connection with starting mechanisms for engines, and is also applicable to such a system where the engine when started, is adapted to store up power to be used for similar future starting operations and various other purposes.

By the 1920s electric self-starters were standard in cars. In 1916, United Motors Corporation, now General Motors, purchased Delco and Kettering worked as Vice President. During his tenure at GM, he invented other items such as the spark plug, shock absorbers, leaded gasoline, and many more. Kettering obtained 186 patents in his lifetime.

Kettering died on November 25, 1958. He was the recipient of many awards such as the IEEE Edison Medal, and the Franklin medal, he also received honorary doctorate degrees and was inducted in the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1979.

An inventor fails 999 times and if he succeeds once, he’s in. He treats his failures simply as practice shots –Charles Kettering.

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm, based in Omaha, NE, serving all of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. If you have any intellectual property questions or need assistance with any patent, trademark, or copyright matters and would like to speak with one of our patent attorneys please contact us.

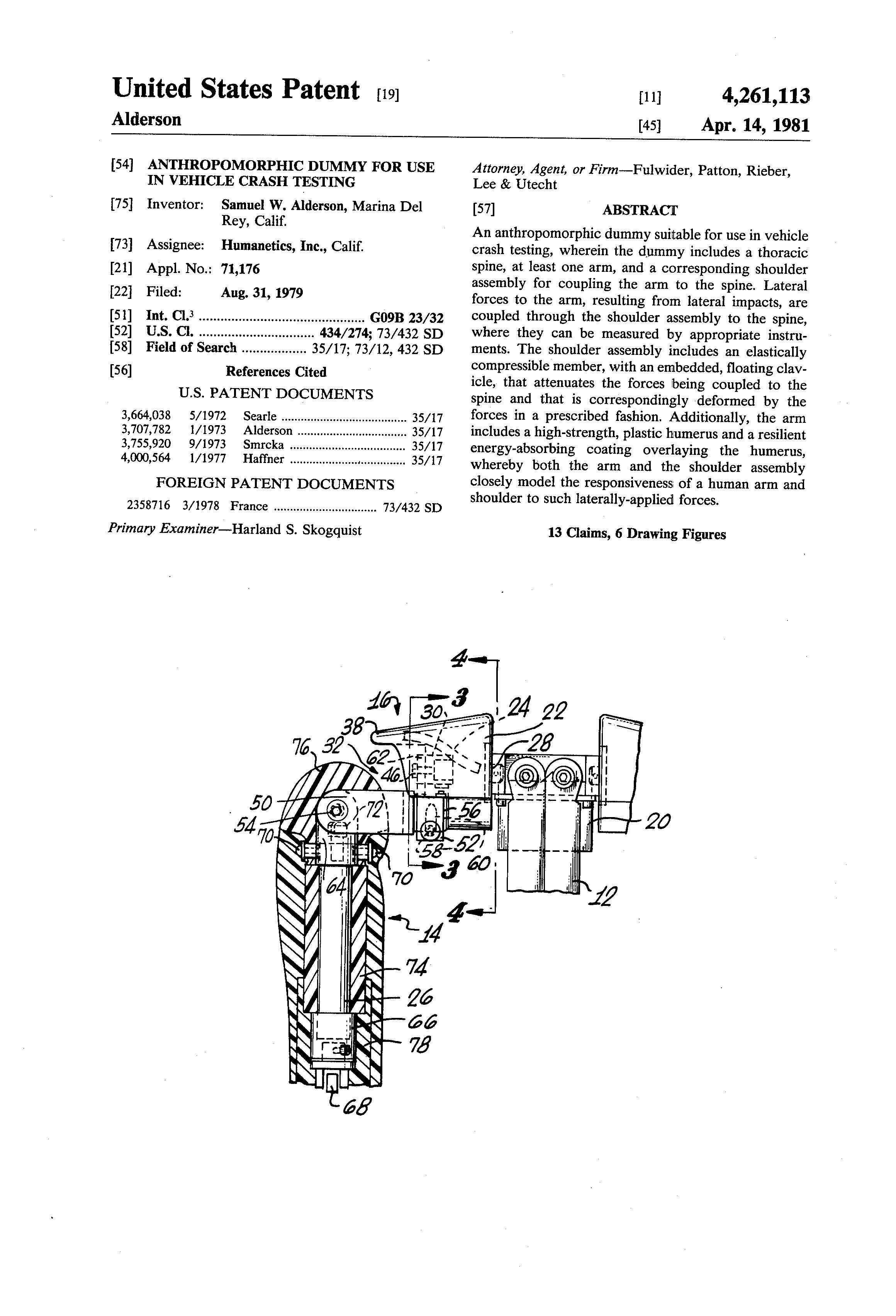

Patent History: Anthropomorphic Dummy for Use in Vehicle Crash Testing

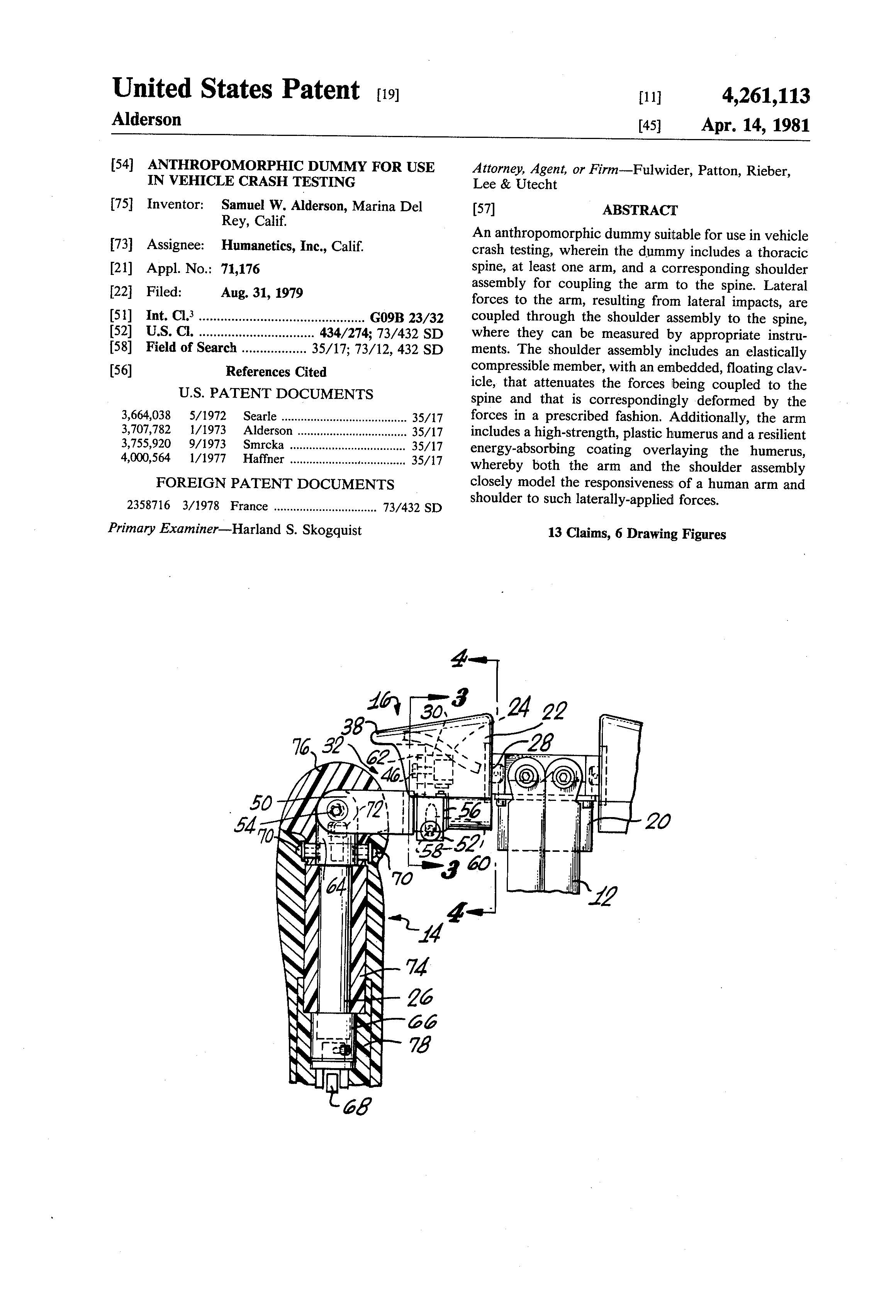

On April 4, 1981, Samuel W. Alderson was granted the patent for “Anthropomorphic Dummy for Use in Vehicle Crash Testing” U.S Patent No. 4,261,113.

Before the 1950s, car manufacturers used living people to test safety features. Medical professionals and engineers would sometimes volunteer as crash test dummies. According to an article titled, “19,000 Animals Killed In Automotive Crash Tests”[1] roughly 19,000 animals, including dogs, rabbits, pigs, ferrets, mice, and rats were killed in automobile safety tests performed by General Motors. Today, neither people nor animals are used in automobile safety testing thanks to Samuel W. Alderson.

Samuel W. Alderson was born on October 21, 1914, in Cleveland, Ohio. His family moved to California where he graduated high school at the age of 15 and went on to attended numerous colleges. His father owned a sheet-metal and sign shop where Alderson would often work in between colleges. He attended Reed College, Caltech, Columbia University, and the University of California Berkeley. He completed his four-year degree and pursued a Ph.D. from UC-Berkley but did not end up completing his doctoral dissertation.

Alderson later worked for IBM where he designed motorized prosthetic arms. In 1952, he started his own company, Alderson Research Labs. Here, he created an arm based product that had mechanical manipulators for handling radioactive materials. Shortly after opening, he was awarded a contract to build and test an anthropometric dummy for aircraft ejection seats.

While Alderson was improving the safety of flights, the automobile industry was struggling with safety as automobile related deaths were on the rise. In need of a way to test and research safety features automobile companies used cadavers, unfortunately, they could not replicate consistent results as no two cadavers were the same. What they needed were human-like dummies that could be tested repeatedly yielding the same results.

The crash-test dummy did not take off until after 1965 when “Unsafe at Any Speed” written by Ralph Nader accused car manufacturers of resisting to introduce safety features. In 1968, Alderson created the first version of the dummy called the VIP. It was designed specifically for automobile testing; it had a steel ribcage, flexible joints, an articulated spine, and had the dimensions of an average adult male.

Today, crash test dummies come in many different forms and represent all different sizes and ages. These dummies are specialized for front, side, and rear impact collisions and have realistic joints with over 200 sensors mounted on the body. These sensors measure things such as the force of the blow, the torque of the neck, compression to the chest, and much more.

The crash test dummies’ sensors’ transmit roughly 10,000 bits of data a second. A typical crash test dummy costs around $600,000, luckily, they can last for up to 20 years.

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm, based in Omaha, NE, serving all of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. If you have any intellectual property questions or need assistance with any patent, trademark, or copyright matters and would like to speak with one of our patent attorneys please contact us.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/1991/09/28/us/19000-animals-killed-in-automotive-crash-tests.html

NSBA's 2018 Business Law Seminar

Suiter Swantz IP Attorney Scot Ringenberg is proud to be a part of 2018 Business Law Seminar where he will discuss intellectual property considerations in business transactions. This seminar will be held Friday, September 14, 2018, at the Gallup campus conference center.

To attend or to learn more about this seminar click here.

Federal Circuit Ruling in Zeroclick, LLC v. Apple Inc.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) issued a decision in a patent infringement suit against Apple (Zeroclick, LLC v. Apple Inc.). The lawsuit, brought by Zeroclick LLC, claims Apple infringed on Zeroclick’s intellectual property with the design of the iOS touchscreen for iPhones.

This lawsuit was first brought by Zeroclick in 2015 where they claimed Apple infringed on their patented technology. The contended patents were U.S. Patent No. 8,549,443 and U.S. Patent No. 7,818,691.

The technology behind the ‘691 and ‘443 patents is described as devices that are “capable of executing software comprising: a touch-sensitive screen configured to detect being touched by a user's finger without requiring an exertion of pressure on the screen;” it also describes the program it would be running on such a device. This technology was originally designed in part for the medical community, potentially making it easier and faster to diagnose patients.

In 2002, Dr. Nes Irvine, inventor of the ‘691 and ‘443 patents, faxed his idea for these devices to the Director of Software Development of Apple, Avie Tevanian. In the fax, Irvine explained the use of the GUI technology and the benefits of it. Five years later, Apple released the first iPhone with technology very similar to what was detailed in the faxes Irvine sent.

It should be noted Apple has a blanket intellectual property policy for anyone who sends anything to them.

Apple’s Intellectual Property Policy states:

You agree that: (1) your submissions and their contents will automatically become the property of Apple, without any compensation to you; (2) Apple may use or redistribute the submissions and their contents for any purpose and in any way; (3) there is no obligation for Apple to review the submission; and (4) there is no obligation to keep any submissions confidential.

It is unclear why Irvine sent the fax to Apple, but after not receiving a response from them, Irvine moved forward with procuring patents on his technologies with Zeroclick as the assignee.

In 2015, the case went before District Court Judge Jon Tigar. He ruled that Zeroclick’s patents were too broad with generic terms. He said the patents did not detail how the technology would work in real life. Tigar cited the “means-plus-function” provision of the patent regulations which states, “[a]n element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.”

Apple argued that limitations “must be construed under § 112, ¶ 6” (the “means-plus-function” provision) but did not give evidentiary reasoning for that position. “Accordingly, Apple failed to carry its burden, and the presumption against the application of § 112, ¶6 to the disputed limitations remained unrebutted.”

The District Court concluded that “the term 'program that can operate the movement of the pointer (0)' is a means-plus-function term because the claim itself fails to recite any structure whatsoever, let alone 'sufficiently definite structure.” The Court further stated “[b]ecause the use of the phrase 'user interface code' provides the same 'black box recitation of structure' as the use of the word 'module' did in Williamson, and the claim language provides no additional clarification regarding the structure of the term, the Court concludes that 'user interface code' constitutes a means-plus-function term.”

The CAFC handed down its decision on June 1, 2018, finding that the district court “erred by effectively treating ‘program’ and ‘user interface code’ as nonce words and concluding in turn that the claims recited means-plus-function limitations.” The CAFC further stated “the district court made no pertinent finding that compels the conclusion that a conventional graphical user interface program or code is used in common parlance as substitute for 'means.'"

The CAFC vacated the district court’s judgment and remanded for further proceedings.

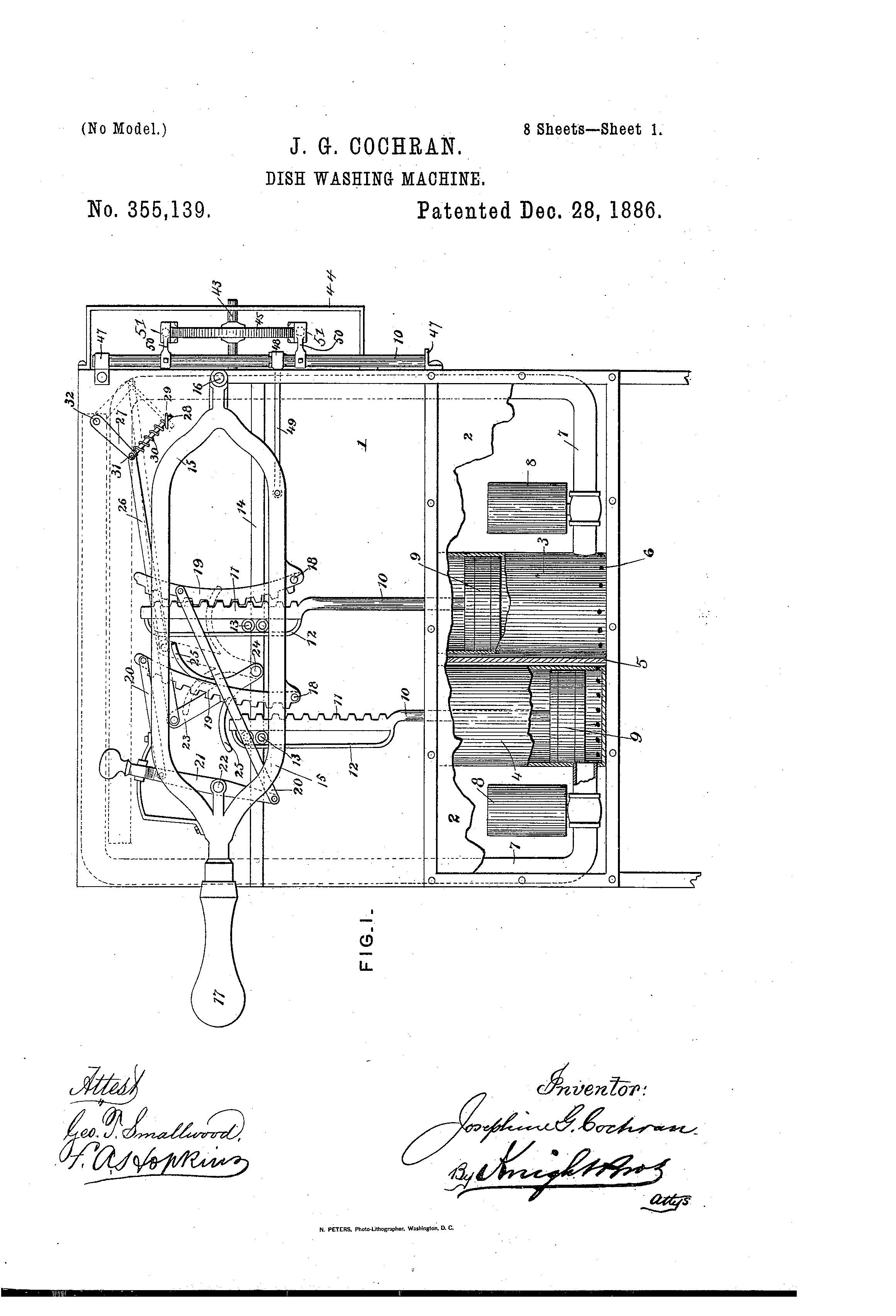

Patent History: Dish Washing Machine

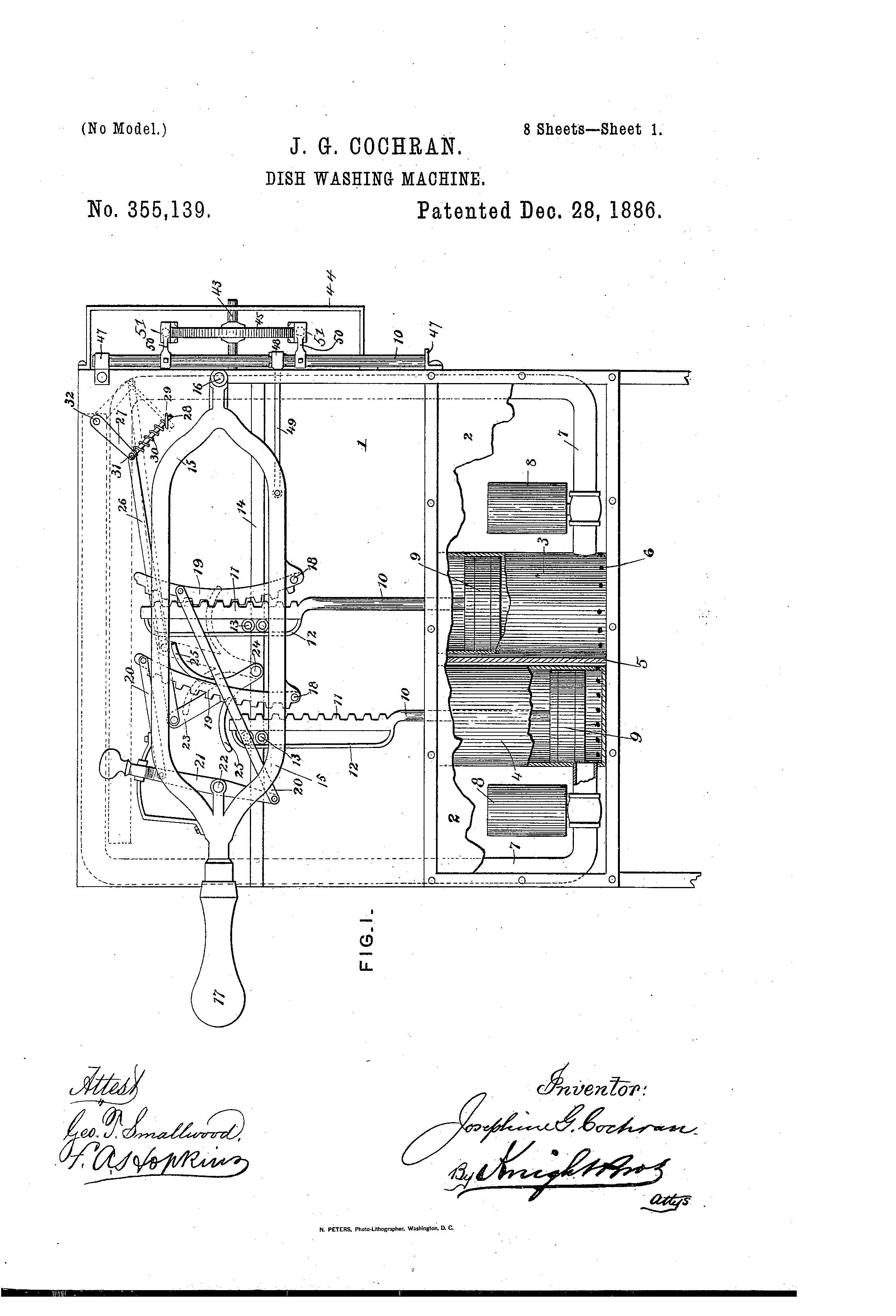

On December 28, 1886, Josephine G. Cochrane was granted the patent for “Dish Washing Machine”, U.S. Patent No. 355,139.

Josephine G. Cochrane was born on March 8, 1839, in Ashtabula County, Ohio. She lived with her father who was a supervisor at a mill as a hydraulic engineer. After graduating high school, Josephine married William Cochran at the age of 19. Josephine took her husband’s name but put an "e" on the end of it as she was known for her independent nature. The Cochrans hosted many dinner parties as William became an affluent, dry goods merchant, investor, and politician who started to rise in the ranks of the Democratic Party.

Cochrane inherited heirloom china that purportedly dated back to the 1600s. After dinner parties, the couple had servants that cleaned up and washed the dishes. After a party, one of the servants accidentally chipped some of the dishes. Angry, Cochrane refused to let the servants handle the china and she washed the dishes instead. Cochrane abhorred this task and thought there had to be an easier way to do this, there are machines for all sorts of things, why not one for dishes. She began to think of a machine that could wash the dishes for her. She said, “If nobody else is going to invent a dishwashing machine, I’ll do it myself.”

In 1883, William Cochran died and left Josephine with a large sum of debt and only $1,535 to her name. Her invention was no longer just a dream but a way to survive financially. She worked relentlessly on her dishwater and the final product had wire compartments in the shape of a wheel where dishes such as silverware, plates, cups, and saucers were placed. A motor turned the wheel and covered the dishes with hot soap from the bottom of a copper boiler.

Cochrane began to share her design and sought the advice of men who, during the late 1800s, had more experience with mechanics than women. Cochrane said, “[t]hey knew I knew nothing, academically, about mechanics, and they insisted on having their own way with my invention until they convinced themselves my way was the better, no matter how I had arrived at it.”

After being steadfast with her invention, Cochrane took her dishwasher to hotels selling the first one to the Palmer House hotel in Chicago. Pleased with her first sale, she knew she would need to sell more but the thought of selling to prominent businessmen was intimidating. When interviewed by a reporter Cochrane said,

You asked me what was the hardest part of getting into business, I think, crossing the great lobby of the Sherman House alone. You cannot imagine what it was like in those days … for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone. I had never been anywhere without my husband or father —the lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn’t—and I got an $800 order as my reward.

She continued to sell her dishwashers, maneuvering her way into restaurants, hospitals, and colleges. Her success allowed her to open her own factory, the Garis-Cochran Manufacturing Company, in an abandoned schoolhouse. She continued to personally sell her dishwashers until her death in 1913. Her company was bought by Hobart which, was later purchased by KitchenAid®, who owns the registrations to Cochrane’s patents and trademarks. KitchenAid was bought out and is now the Whirlpool Corporation.

The automatic dishwasher is now a staple in homes across the country. Every time you load the dishwasher and don’t have to hand wash dirty dishes you can thank Josephine Cochrane.

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm, based in Omaha, NE, serving all of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. If you have any intellectual property questions or need assistance with any patent, trademark, or copyright issues and would like to speak with one of our patent attorneys please contact us.

Supreme Court to Hear On-Sale Bar Case

The Supreme Court of the United States granted a petition for writ of certiorari in Helsinn Healthcare S.A. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA Inc. This will be one of the first cases to address the rewriting of on-sale bar language, of 35 U.S.C. §102.

The question presented before the Supreme Court was:

Whether, under the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, an inventor's sale of an invention to a third party that is obligated to keep the invention confidential qualifies as prior art for purposes of determining the patentability of the invention.

On-sale bar refers to a patent that is deemed invalid because the invention was on sale a year or more prior to the date the patent application was filed.

In 2001, Helsinn entered into a Supply and Purchase agreement with MGI Pharma, Inc. A press release was made in regard to the agreements and MGI supplied a redacted copy of the agreements omitting the price and dosage formulation for Helsinn’s anti-nausea drug, Aloxi.

In 2011, Teva sought FDA approval for a generic version of Aloxi and Helsinn sued claiming patent infringement. Due to the Supply and Purchase agreements, Teva argued Helsinn’s patents were invalid under the on-sale bar. The District Court disagreed, found in favor of Helsinn, and concluded the agreements were for future sales and the drug was not ready for patenting at the time the companies entered into the agreements. As for the post AIA patent, the Court found that yes, the agreement was made public, but, the dosage information was not.

Teva appealed the District Court’s ruling and in May 2017, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) heard the case. The CAFC held that certain patents for Helsinn’s anti-nausea drug, Aloxi, were invalid. The CAFC further held that Helsinn’s patented claims “were subject to an invalidating contract for sale prior to the critical date,” and, “the AIA did not change the statutory meaning of ‘on sale’ in the circumstances involved here.” The Court also concluded that Helsinn’s “invention was reduced to practice and therefore was ready for patenting before the critical date” of January 30, 2002.

The CAFC’s final conclusion stated:

We hold that the asserted claims, claims 2 and 9 of the ’724 patent, claim 2 of the ’725 patent, claim 6 of the ’424 patent, and claims 1, 2, and 6 of the ’219 patent, are invalid under the on-sale bar.

Under revised 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1), a person is entitled to a patent unless “the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.” Helsinn believes the Congress added the phrase “or otherwise available to the public” to eradicate “secret sales” as prior art and to require that the sale(s) make the “claimed invention” “available to the public.”

In its petition, Helsinn referenced the definition of prior art and stated it is “critically important” and “goes to the heart of patentability.” They feel the AIA has narrowed the scope of on-sale bars to sales that are “publicly available.” Helsinn further stated “[t]he Federal Circuit’s decision threatens to upend that carefully constructed system…[it] casts doubt on the validity of countless patents issued since the AIA took effect and will chill valuable collaborations by smaller innovators.”

The Supreme Court is expected to hear this case in the fall with a decision to follow in early 2019.

Helsinn attorney Joseph O’Malley said: “We are pleased that the Supreme Court will consider the validity of the patent covering our client’s Aloxi drug franchise and clarify the AIA’s on-sale bar provision.”

A spokesperson for Teva said: “We acknowledge that the Supreme Court granted further review, but we remain confident in our position on the merits.”

Many hope this case will clarify discrepancies that have led to increased confusion for patentees and lower courts in regard to past on-sale bar rulings.

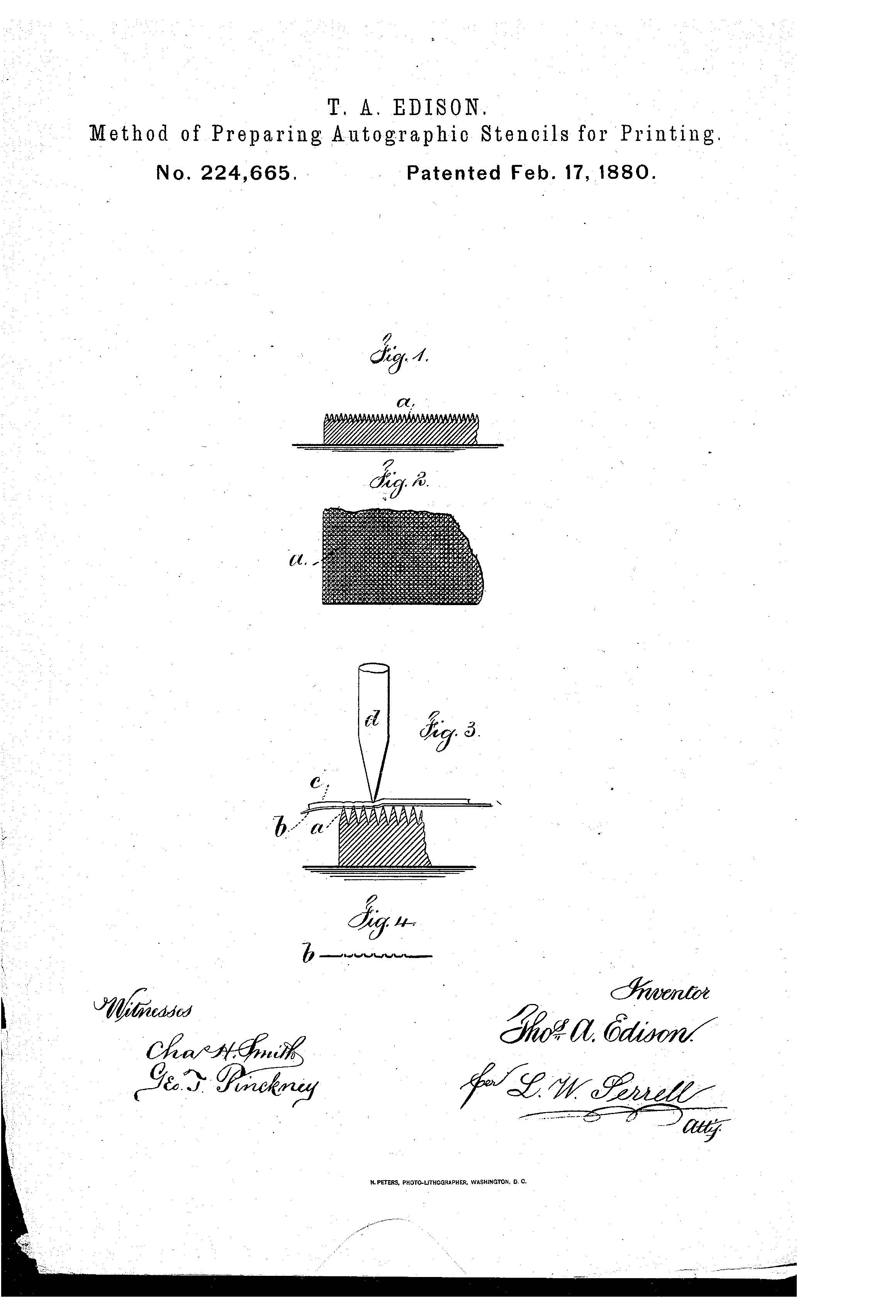

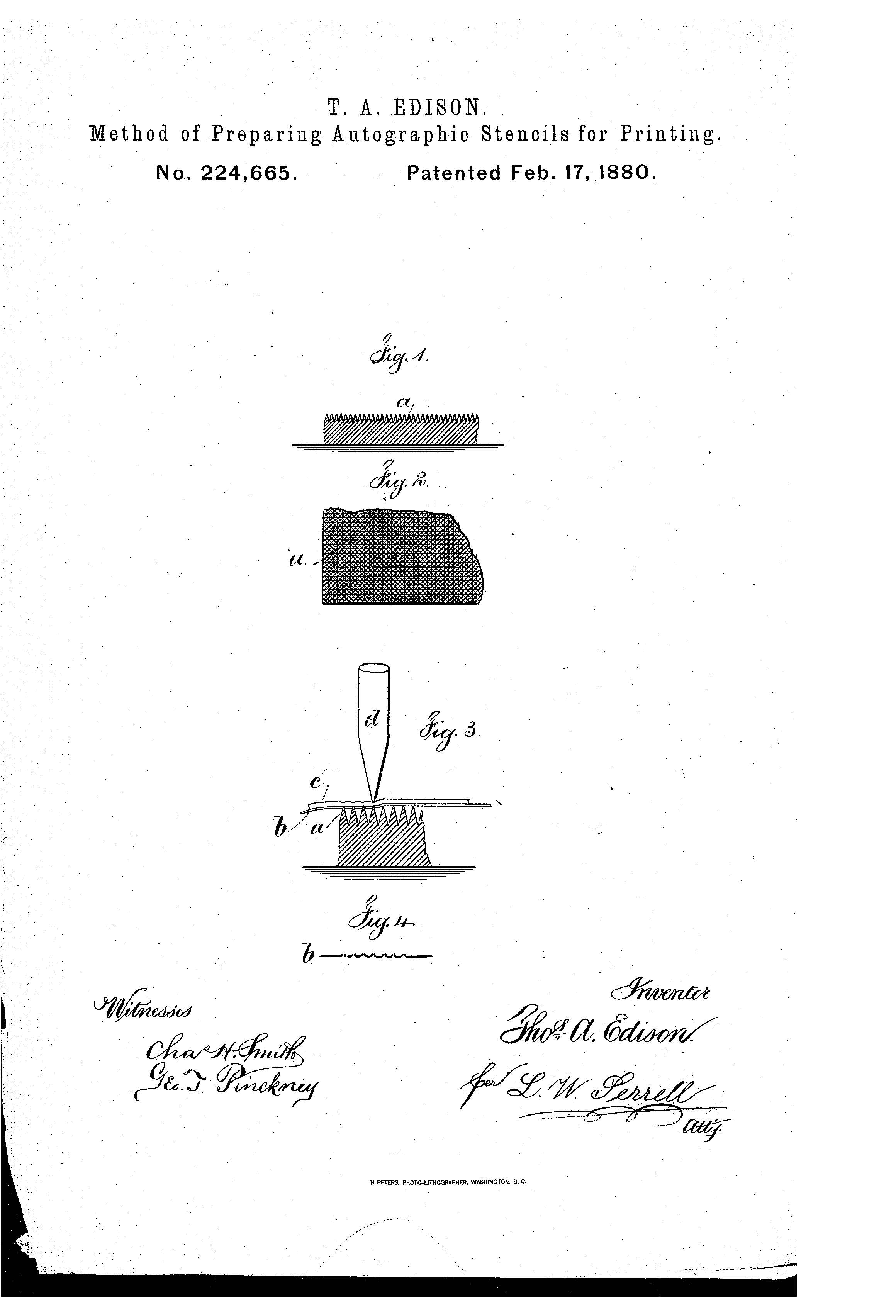

Patent History: Method of Preparing Autographic Stencils for Printing (Mimeography)

On this day in 1876, Thomas Edison received a patent for the Mimeograph, entitled “Method of Preparing Autographic Stencils for Printing,” U.S Patent No. 224,665. The Edison’s invention involved a method of preparing autographic stencils for printing on wax paper. Mimeographs were used in classrooms, small offices, and small organizations to print bulletins in large numbers. It is believed that almost all military personnel orders given during World War II were composed and run on mimeographs.

The method utilized by Edison’s mimeograph involves the following:

…preparing stencil sheets for printing, consisting in pressing the sheet in the lines to be printed against the numerous fine perforating-points of a slab by means of a blunt stylus that is passed over the sheet at the lines to be perforated.

In 1887, Edison partnered with Chicago inventor Albert Blake Dick, who improved Edison’s stencils, licensed the patent, and manufactured the stencil equipment for the mimeograph. In 1887, the duo also released the “Model 0” mimeograph and sold it for $12.

The Princeton University Library has an original “Model 0” on display. The description of how to use the mimeograph states: “To prepare a handwritten stencil, a sheet of mimeograph stencil paper is placed over the finely grooved steel plate and written upon with a smooth pointed steel stylus, and in the line of the writing so made, the stencil paper will be perforated from the underside with minute holes, in such close proximity to each other that the dividing fibers of paper are scarcely perceptible.”

The mimeograph remained in use for almost a century after it was patent as it proved to be a cheaper and more efficient option to competing technologies. As technology advanced so did the mimeograph. Newer versions of the mimeograph included hand-cranks or motors. As with all technologies, the mimeograph eventually became obsolete and was replaced by the photocopier, which can process print jobs at a much faster rate than the mimeograph.

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm, based in Omaha, NE, serving all of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. If you have any intellectual property questions or need assistance with any patent, trademark, or copyright matters and would like to speak with one of our patent attorneys, please contact us.

Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and Trademarks

Sturgis, South Dakota is home to the world’s largest motorcycle rally. Sturgis® Motorcycle Rally started in 1938 with only nine participants and it was called the Black Hills Classic. After the first Black Hills Classic, the name was changed to the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally. In 2000, the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally exceeded 600,000 attendees and has grown to 750,000 attendees in 2015. Now, it is a ten-day rally with concerts, camping, riding, and street foods. There are even tattoo, beard, and mustache contests. As the rally grew, people felt it needed to have an official logo. Artist Tom Monahan stepped in and donated his artwork to the South Dakota Commerce with the agreement that he would be the only vendor allowed to sell shirts with the official logo.

Over the years, vendors realized the importance and value in the official logo and became licensed vendors through the Chamber. In 2010, the Sturgis Motor Rally Inc. (SMRi) bought the trademarks from the Chamber. Now, SMRi has trademarks and copyrights on Sturgis®, Black Hills®, The Legend Lives On®, Sturgis Bike Week®, Take the Ride to Sturgis®, Sturgis® Motorcycle Rally™, Sturgis Rally & Races™ as well as five current logos.

SMRi has defended their trademarks against many people and organizations, including Rushmore Photo and Gifts (RPG) and Wal-Mart. SMRi sued RPG and Wal-Mart for unlawfully distributing trademarked Sturgis merchandise.

In a countersuit, RPG argued that “names that are geographically descriptive of a place cannot be trademarked. One exception: If a trademark applicant can prove it was the exclusive user of a geographic name for five years, a trademark could be filed.”

The court entered judgment in favor of SMRi in December of 2015. SMRi argued that RPG “is not a Sturgis, South Dakota, based business and is therefore outside plaintiff’s concession permitting the geographic use of the term ‘Sturgis’” is disingenuous.”

The jury ordered RPG to pay SMRi damages in the amount of $900,000, Wal-Mart was ordered to pay $235,000 in damages.

RPG appealed that ruling and in 2017, Jeffrey Viken, Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court of South Dakota, Western Division, vacated the original damages ruling. Aaron Davis, attorney for RPG felt this ruling was not the best outcome as the Judge upheld SMRi’s trademark rights.

While many may not look to Sturgis for case law, this case has definitely set a precedent for other businesses dealing with similar situations.

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm, based in Omaha, NE, serving all of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. If you have any intellectual property questions or need assistance with any patent, trademark, or copyright matters and would like to speak with one of our patent attorneys please contact us.

Patents, The Hatch-Waxman Act, and Pharmaceutical Companies

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, was enacted to balance incentives for both pharmaceutical innovation and drug affordability by allowing generic drug manufacturers to challenge patents of brand name drugs via Abbreviated New Drug Applications (“ANDA”) with the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”). The Hatch-Waxman framework incorporates distinctive rules that allow generic drug manufacturers to lawfully reverse-engineer a brand-name drug while at the same time providing the brand-name manufacturer, or innovator, a period of exclusivity to recoup its investment.

In 2012, the inter partes review (“IPR”) and post-grant review (“PGR”) processes were introduced by the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (“AIA”) and are administrative trial proceedings conducted by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) to allow any third party to challenge a patent based on a lack of novelty (§ 102) or obviousness (§ 103). The IPR was created to provide a faster and cheaper way to challenge patent validity than traditional litigation. An increasing number of generic drug manufacturers have used the IPR and PRG processes to circumvent the Hatch-Waxman Act while taking advantage of the abbreviated processes for drug entry.

On June 13, 2018, Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT), Chairman of the Senate Republican High-Tech Task Force and co-author of the Hatch-Waxman Act, filed an amendment in the Senate Judiciary Committee to restore the balance the Hatch-Waxman Act struck to incentivize generic drug development. Senator Hatch’s amendment, the Hatch-Waxman Integrity Act of 2018, would close the loophole created by the AIA and would require generic drug manufacturers wishing to challenge a brand-name drug patent to choose between Hatch-Waxman litigation, which affords certain advantages such as being able to rely on the drug innovator’s safety and efficacy studies for FDA approval, or IPR, which is cheaper and faster than Hatch-Waxman litigation, but does not provide the advantages of a streamlined generic approval process.

For generic drugs, any Paragraph IV certification would have to include the following additional certifications:

- Neither the applicant nor any party in privity with the applicant has filed, or will file, a petition to institute inter partes review or post-grant review of that patent under chapter 31 or 32, respectively, of title 35 United State Code

- In making the certification required under subparagraph (A), the applicant is not relying in whole or in part on any decision issued by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board in an inter partes review or post-grant review under chapter 31 or 32, respectively, of title 35 United State Code

A similar provision is designed for biosimilar drugs under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA).

As stated in Senator Hatch’s amendment, the purpose of the Hatch-Waxman Integrity Act is:

To prevent the inter partes review process for challenging patents from diminishing competition in the pharmaceutical industry and with respect to drug innovation.

To promote competition in the market for drugs and biological products by facilitating the timely entry of lower cost generic and biosimilar versions of those drugs and biological products.

Overall, the Hatch-Waxman Integrity Act would prevent generic drug manufacturers from challenging patents in both the PTAB, while seeking FDA approval via the ANDA pathway.

Three Suiter Swantz IP Attorneys Selected as "Rising Stars" for 2018

Suiter Swantz IP would like to congratulate Matt Poulsen, Nicholas Grennan, and Faisal Abou-Nasr on being selected as “Rising Stars” by Super Lawyers. Super Lawyers is a research-driven, peer-influenced rating service of outstanding lawyers who have attained a high degree of professional achievement and peer recognition. Congrats Matt, Nick, and Faisal!

Suiter Swantz IP Welcomes Intellectual Property Paralegal Laura Blair

Laura Blair joined Suiter Swantz IP in 2018 as an intellectual property paralegal for the Firm. She has over 37 years of experience in intellectual property, specializing in patent prosecution. Prior to joining Suiter Swantz IP, Laura worked for an intellectual property law firm in Alexandria, Virginia for 15 years where she managed the patent portfolio of many large corporations.

Outside the office, Laura enjoys playing pool on a league and spending time with family.