February is Black History Month and all of us at Suiter Swantz IP wanted to take this opportunity to take a look at some of the African American inventors, innovators, and scientists who have helped shape innovation and the U.S. patent system.

The modern United States patent system has been in existence for well over two hundred years. The very first U.S. patent was granted in 1790, at a time in which slavery was very much alive. During this bleak and loathsome time period of American history, African Americans born into slavery were not considered U.S. citizens, and were forbidden by law from applying for or holding property. As a form of intellectual property, this included patents. This seemingly blanket prohibition on slave-owned property was affirmed by the U.S. Commissioner for Patents in 1857, when it was officially ruled that inventions by slaves could not be patented.

Although the law of the land could prevent slaves from owning patents, the law could not, and did not, stop them from inventing and innovating.

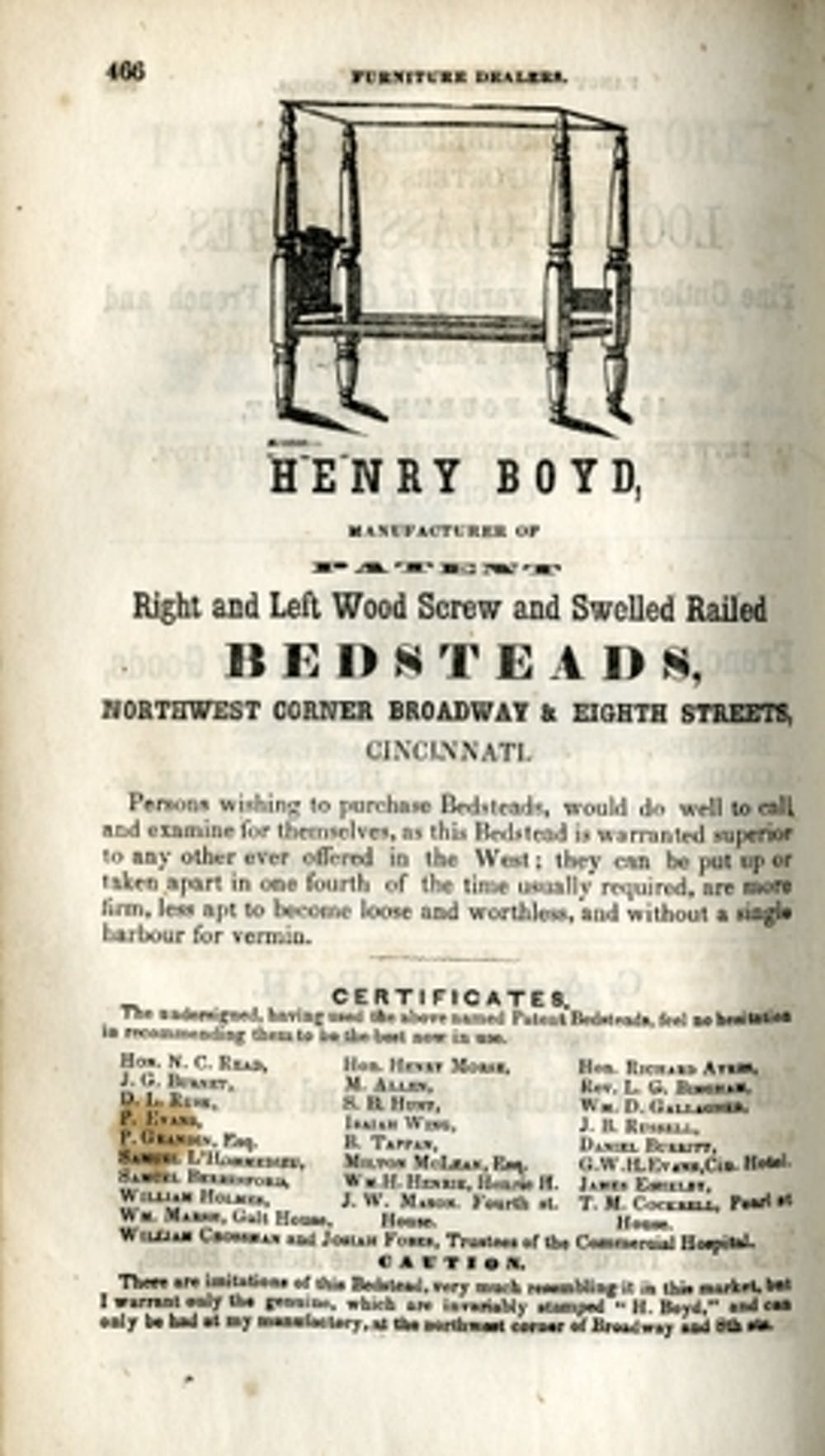

Henry Boyd

Henry Boyd was born into slavery in 1802. From a young age, Boyd knew he wanted to be a carpenter. He learned the trade early in life and quickly became skilled in the craft. Through his craftsmanship, Boyd was able to earn a substantial amount of money, which he used to purchase his freedom in 1826. As a newly-freed man, Boyd moved to Cincinnati where he continued his career as a carpenter building homes. His skill and expertise as a carpenter allowed him to purchase the freedom of his sister  and brother. At the age of 34, Boyd started his own company which specialized in making bed frames. As a product of this new venture, Boyd invented the “The Boyd Bedstead,” a bed constructed of wooden rails that connected the headboard and footboard together. This new construction provided increased durability and stability, and is still widely used today.

and brother. At the age of 34, Boyd started his own company which specialized in making bed frames. As a product of this new venture, Boyd invented the “The Boyd Bedstead,” a bed constructed of wooden rails that connected the headboard and footboard together. This new construction provided increased durability and stability, and is still widely used today.

As a freed man, Boyd attempted to patent his invention. Even as a freed man, the Patent Office denied his application. Undeterred, Boyd partnered with a Caucasian craftsman, George Porter. Under this arrangement, Porter applied for a patent on the Boyd Bedstead, and was granted the patent on December 30, 1833 (U.S. Patent No. X7911). Although the patent was not in Boyd’s name on paper, that did not stop him from making the beds and stamping his name on each and every of them.

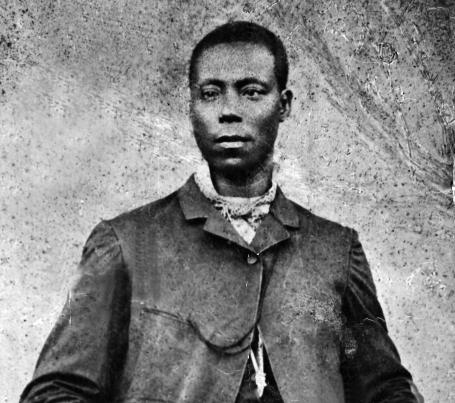

Thomas Jennings

Born in 1791 as a free African American in New York City, Thomas Jennings began his career as a tailor and dry-cleaner. Jennings was so skilled people came from all over to receive custom-tailors and alterations. His skill and reputation allowed him to eventually open a tailoring and dry-cleaning shop on Church Street, which became one of the largest clothing stores in New York City. In 1820, Jennings invented a process called dry-scouring, a process similar to that of modern-day dry-cleaning. He was granted a patent on the dry-scouring process on March 3, 1821 (U.S. Patent No. X3,306), making him the first African American to receive a patent.

Born in 1791 as a free African American in New York City, Thomas Jennings began his career as a tailor and dry-cleaner. Jennings was so skilled people came from all over to receive custom-tailors and alterations. His skill and reputation allowed him to eventually open a tailoring and dry-cleaning shop on Church Street, which became one of the largest clothing stores in New York City. In 1820, Jennings invented a process called dry-scouring, a process similar to that of modern-day dry-cleaning. He was granted a patent on the dry-scouring process on March 3, 1821 (U.S. Patent No. X3,306), making him the first African American to receive a patent.

In addition to being known as the first African American to receive a patent, Jennings is also remembered as a civil rights activist and for his extensive work with the abolitionist movement. In 1831, Jennings became the assistant secretary for the First Annual Convention of the People of Color in Philadelphia.

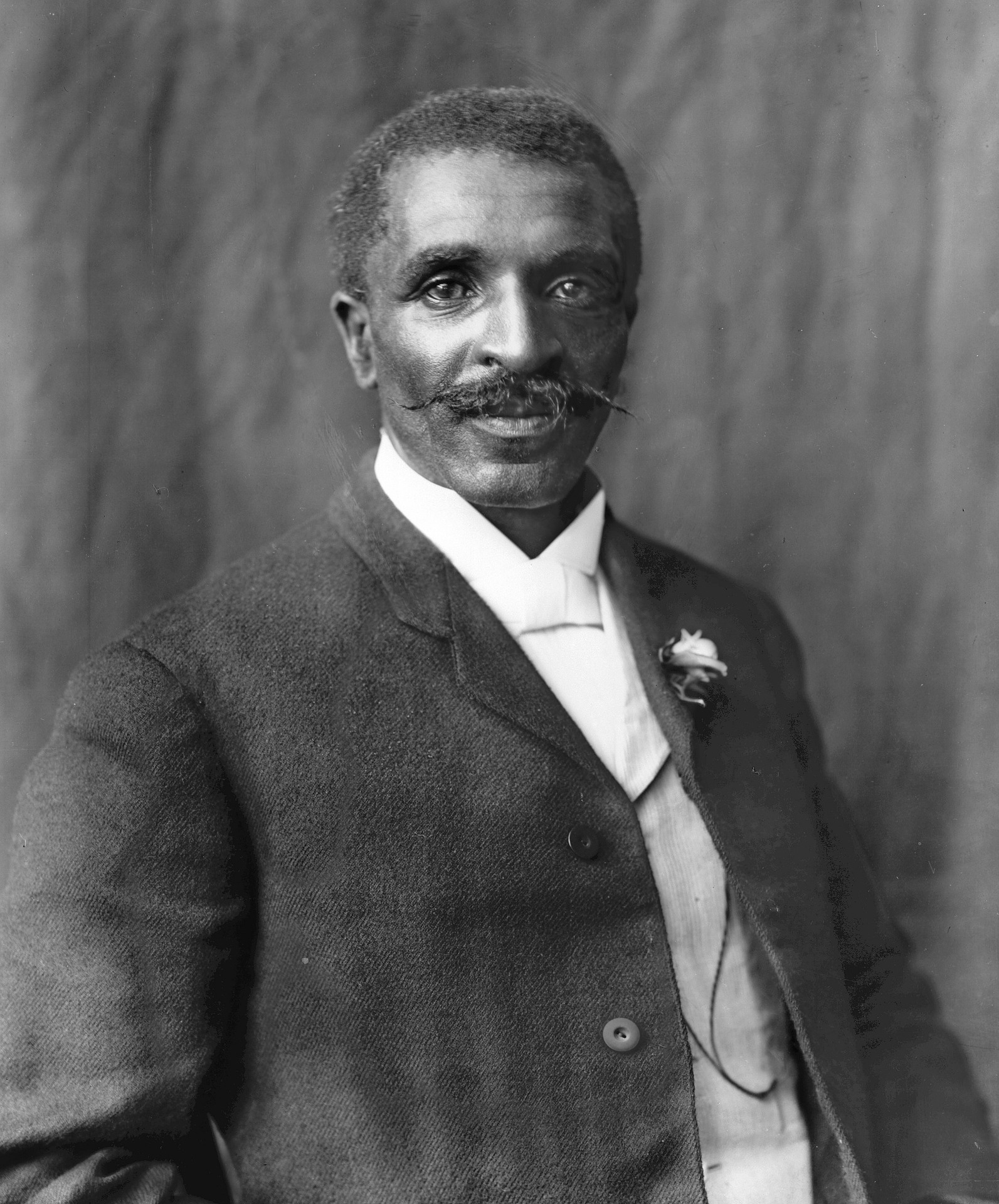

George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver was born into slavery in 1864. Following the abolition of slavery, Carver’s former owners, Moses and Susan Carver, raised Carver as one of their own, teaching him how to read and write. In addition to helping out with daily chores, Carver would observe “Aunt Susan” make herbal medicines. This sparked an interest in Carver that he would maintain throughout the rest of his life. Carver began to experiment with plants, pesticides, soil conditions, etc., and became known as the “plant doctor,” helping neighboring farmers improve their crops and fields.

George Washington Carver was born into slavery in 1864. Following the abolition of slavery, Carver’s former owners, Moses and Susan Carver, raised Carver as one of their own, teaching him how to read and write. In addition to helping out with daily chores, Carver would observe “Aunt Susan” make herbal medicines. This sparked an interest in Carver that he would maintain throughout the rest of his life. Carver began to experiment with plants, pesticides, soil conditions, etc., and became known as the “plant doctor,” helping neighboring farmers improve their crops and fields.

As an African American, it was not easy for Carver to earn a formal education. After much searching, he was able to attend the School for African American Children in Neosho, Kansas, which was a 10 mile walk from Carver’s home. At the age of thirteen, Carver left home to continue his high school education. Following high school, Carver received a scholarship to attend Highland Presbyterian College in Kansas. The scholarship was short lived, however, as the school turned him away on the first day of school upon learning that he was black.

Despite this setback, Carver was accepted into Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, in 1888, making him the first black student to attend the school. Carver’s interest in botany led him to Iowa State Agriculture School (now Iowa State University) where he earned his Bachelor of Science degree in 1894. The school was so impressed with his work they asked him to stay on as faculty while earning his Master’s degree, which he obtained in 1896.

Through his interest and research in botany, Carver was granted two patents in 1925 and 1927, entitled COSMETIC AND PROCESS OF PRODUCING THE SAME (U.S. Patent No. 1,522,176) and PROCESS OF PRODUCING PAINTS AND STAINS (U.S. Patent No. 1,632,365). In 1990, Carver was the first African American inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. As a successful scientist, Carver invented countless methods and products which could have been patented, yet Carver only patented three of these inventions. When asked why he hadn’t patented more of his inventions, he stated: “[If] I did it would take so much time, I would get nothing else done. But mainly I don’t want my discoveries to benefit specific favored persons.”

Rebecca Cole

Born in Philadelphia in 1846, Rebecca Cole attended the prestigious Institute for Colored Youth. With an eye towards training black youth to become teachers and scholars, the school boasted an intense curriculum that included Greek, Latin, and Mathematics. Cole excelled in school and graduated in 1863.

Cole went on to become the second African American woman to receive a Master’s degree in the United States. Following graduation, Cole attended medical school at the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania. Cole graduated in 1867, and was the first African American woman to obtain her M.D. from the school. As a med school graduate, Cole moved to New York City and began work at the Infirmary for Women and Children, one of the earliest programs for medical social services. She became a social activist and worked as the superintendent of the Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children in Washington D.C. Although there is little information about Cole outside of her work in the medical field, her passion for providing health care to impoverished women and children paved the way for women, and African American women especially, to pursue careers in science and medicine.

One woman who followed down a similar path as Cole was Marie M. Daly (pictured left). Daly is best known as being the first African American woman to receive her Ph.D. in chemistry. Betty W. Harris also exceled in the chemical field and received her Ph.D. in chemistry. Harris was intrigued by explosives and became a noted expert in the field. She went on to patent SPOT TEST FOR 1,3,5-TRIAMINO-2,4,6-TRINITROBENZENE TATB (U.S. Patent No. 4,618,452).

One woman who followed down a similar path as Cole was Marie M. Daly (pictured left). Daly is best known as being the first African American woman to receive her Ph.D. in chemistry. Betty W. Harris also exceled in the chemical field and received her Ph.D. in chemistry. Harris was intrigued by explosives and became a noted expert in the field. She went on to patent SPOT TEST FOR 1,3,5-TRIAMINO-2,4,6-TRINITROBENZENE TATB (U.S. Patent No. 4,618,452).

Dr. Patricia Bath (pictured right) is known as becoming one of the first African American women to receive a medical patent. She was granted the  patent for APPARATUS FOR ABLATING AND REMOVING CATARACT LENSES in 1988 (U.S. Patent No. 4,744,360). Bath was also the first African American to complete a residency in ophthalmology, and also the first woman faculty member in the department of Ophthalmology at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute. Her love of ophthalmology led her to co-found the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness.

patent for APPARATUS FOR ABLATING AND REMOVING CATARACT LENSES in 1988 (U.S. Patent No. 4,744,360). Bath was also the first African American to complete a residency in ophthalmology, and also the first woman faculty member in the department of Ophthalmology at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute. Her love of ophthalmology led her to co-found the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness.

African Americans have played a vital role in shaping innovation in this country. The effects of these and numerous other African American inventors can be felt every single day in the United States and around the world.

Suiter Swantz IP is a full-service intellectual property law firm, based in Omaha, NE, serving all of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota. If you have any intellectual property questions or need assistance with any patent, trademark, or copyright matters and would like to speak to one of our attorneys please contact us.